Not all recreational shrimpers are created equal. Here’s how to get the most from the 2007 shrimp-baiting season.

As the days become shorter and the nights longer, autumn brings many riches to outdoor enthusiasts across the state.

Through the season, South Carolinians pound the water and beat the bushes to bring home some sort of wild critter for dinner. What could be better to drop in a boiling pot of seasoned broth with sausage and potatoes or battered in flour and dropped in hot grease than a mess of jumbo shrimp?

It is no mystery when the recreational shrimp-baiting season opens. Every public boat ramp along the coast is littered with boats wreaking of the aroma of ground fish meal and displaying a wad of 14-foot poles hanging off the stern

Shrimp baiting is extremely popular in South Carolina, and it is primarily restricted to state residents, who pay a $25 fee for licensed/tagged poles. Nonresidents can assist a licensed resident while shrimping, but they must pay $500 for a license to shrimp independently.

Unlike neighboring states, South Carolina fishermen are blessed with a recreational shrimp-baiting season. Starting in mid-September and continuing through mid-November, the 60-day season allows for an abundant harvest. The season opens at noon on the Friday before Sept. 15 and lasts exactly 60 days, closing at noon on the final day.

The Shrimp

Three species of shrimp live along the South Carolina coast: white, brown, and the rare pink shrimp. White and brown shrimp make up 95 percent of the harvest, including recreational and commercial catches. Pink shrimp prefer sandy and firm bottoms. Many of S.C.’s estuaries have muddy bottoms that are more suitable for white and brown shrimp. The brackish waters of the coastal estuaries provide a rich nutrient and food base for rapid growth. Brown shrimp and small white shrimp dominate the early portion of the season. As it progresses through October and November, creels become completely made of fully grown white shrimp.

White and brown shrimp are fairly similar in appearance, but they have different habits and life histories. The recreational season primarily targets white shrimp. White shrimp tend to become larger and more concentrated during the staging period, within the shallows adjacent to deep water and shallow marsh grass. Brown shrimp prefer the protection of deeper channels while staging.

By the start of the season, the majority of brown shrimp have already migrated into the ocean to spawn. Adult brown shrimp spawn in the ocean during the late summer and early fall, dependent on an ideal water temperature. Brown shrimp larvae overwinter in the ocean until the water temperatures rises in the spring, allowing them to migrate into the nutrient rich estuaries. From mid-July through September, brown shrimp stage in estuaries close to the ocean and eventually move into the ocean to spawn.

White shrimp spawn close to shore during the spring. The larvae immediately move inshore, with the help of rising flood tides, into the nursery grounds of brackish marshes. White shrimp spend the summer growing and fleeing from predators.

Shrimp migration and reproduction is strongly tied to environmental factors, including: salinity, water temperature, lunar cycles, and daylight. Premature migrations into the ocean are specifically caused by an abnormal salinity level. Salinity is heavily united with rainfall. Periods of heavy rain or drought will adversely affect shrimp populations, forcing premature migrations. Too much rain lowers the salinity, and drought conditions raise the salinity. Premature migration is detrimental to the shrimp population because of limited forage and habitat, as well as increased predation.

Water temperature only affects shrimp during the spring and fall. A early, extended cold snap will force the shrimp out of estuaries into the ocean before the recreational season ends. Extended periods of cold weather during the winter can kill thousands of shrimp, reducing the overall population.

The lunar cycle and length of daylight hours (the photo-period) control movements of shrimp somewhat; they utilize the strength of tidal currents to travel from place to place. The excessive lunar pull during a new moon and full moon increases the velocity of currents, providing a fast track for shrimp during a migration period.

Daylight affects shrimp, which are spooky and prefer to travel during the safety of darkness.

The Location

Well known across the region for his dynamite shrimping skills, Capt. Steve Hedrick of Reel EZ Charters in Georgetown has overcome the complications of shrimping in his home waters. Every coastal community has an expert for specific kinds of fishing, and Hedrick is the shrimp chief.

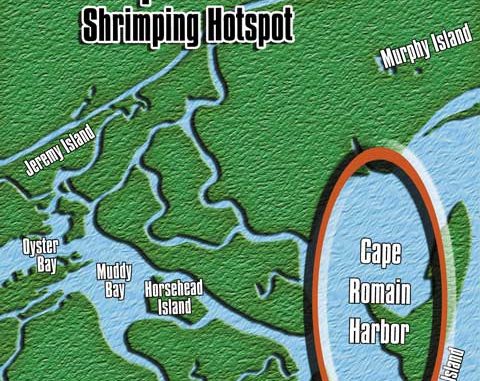

According to Hedrick, the hottest shrimping grounds are from Winyah Bay to Bulls Bay; more specifically, the Muddy Bay area of Winyah Bay, the Cowpens area (Cowpens Point) and around the white banks, bird islands, and adjacent to Bulls Creek in Bulls Bay.

“Winyah is loaded with shrimp and has far less pressure than areas further to the south, but the shrimp are smaller too. The Cowpens Area and Bulls Bay produce whopper shrimp, but with lots of crowds to fight with during the season,” Hedrick said.

Hot spots tend to carry over from year to year, and each end of the pole sequence should be located using a GPS receiver.

The Technique

Finding a good area is just the start to filling a cooler with shrimp. Finding the perfect bottom substrate, water clarity, and water conditions are important to catching shrimp. Hedrick seeks out firm bottoms made of compacted mud.

“Stay away from soft ‘pluff mud’ bottoms and hard bottoms with oyster shells and sand,” he said.

Since shrimp are a delicacy and primary food source for almost every fish and crab in the estuary, they tend to stay on the defensive by trying to conceal themselves. Shrimp tend to stick tight to cover under clear water conditions, but they will venture out at night or during murky conditions during the daytime. Daytime shrimping is more productive in cloudy and murky water. The murky waters around Georgetown and the Bulls Bay are ideal for daytime shrimping.

Regulations allow each boat to use a maximum of 10 poles around which bait is placed. Poles must be used; no bait is allowed to be placed in the water without poles. Knowing where to place poles and in what configuration tends to be a mystery. Some people place their poles parallel or perpendicular to the channel, while others stay away from the channel completely.

Hedrick prefers to place his poles near a creek channel, but not directly in the channel. During the season, shrimp are on the move and will use the creek channels as a freeway system, but they will leave them to feed.

Hedrick doesn’t prefer either tide, but he does favor moving water over dead high or low tidal periods. He attributes poor success at dead or still tides to increased predation from whiting and pinfish.

Shrimping takes at least two people to set out poles, bait them and fish the poles.

Poles are driven or pushed into the pottom by hand in a single-file line, and the configuration of bait patties is dropped as the poles are set. After all 10 poles are set and baited, the first pole can be fished, but many fishermen choose to wait 20 to 30 minutes for the shrimp to find the bait. The setup can be fished continuous from start to finish until a limit is captured. Poles may need to be refreshed with new bait balls as the others are consumed or wash away with the current.

Routinely, the first setup is not always the best, and after an hour of fishing with little success, a new location might be an option.

Capt. Fred Rourk of Sweet Tea Charters in Georgetown is an experienced inshore guide who specializies in redfish and winter trout. He was raised in the marshes of Port Royal Sound shrimping with his brother, Capt. Danny Rourk of Tailwind Charters in Beaufort.

Since the waters are crystal clear along the southern part of the coast, the Rourks use a technique that ensures quick catches. They make poles out of bamboo and place them — along with the bait patties — next to the marsh grass in about one foot of water at low tide in the evening.

Shrimp hold in deeper water and wait until dark to venture into the marsh grass to feed. As the tide begins to rise, the shrimp find the bait patties on the way to the grass and congregate.

“There is a easy dinner waiting on them, and they stop for dinner. As night falls, start throwing as soon as the water touches the grass, and they will be there stacked like cord wood,” Fred Rourk said.

Areas along the coast that are without rivers pouring into the ocean make for ultra-clear water conditions, such as Charleston and the Beaufort Areas.

“Shrimping at night is the trick in the Lowcountry,” Rourk said.

As mentioned before, shrimp are spooky, and clear-water situations are better suited for after-dark action. In areas where rivers dump sediments into the estuaries, the water is murky and cloudy. These areas allow for shrimping during the day or night with similar results.

“Add an algae bloom to the mix, and it improves the shrimping during the daytime anywhere along the coast,” Hedrick said.

The Bait

“Bait is the key to catching shrimp. As simple as it sounds, choosing the right bait configuration and bait type is controversial,” Hedrick said.

The standard method is to buy dry, ground menhaden meal from a milling company and mix it with commercial clay or creek mud to form patties or balls.

Some sort of binding agent is necessary to contain the fish meal in a concentrated patty. The Roarks went through every mixture known to man for making bait patties using fiddler crab mud and clay, but they ended up using bleached wheat flour.

Hedrick has a problem with commercial fish meal. “Much of it is combined with corn. That is not good for trying to lure in shrimp. Corn is for hogs,” said Hedrick, who prefers to use Shrimper’s Choice (www.shrimpers-choice.com), a premixed concoction made of ground menhaden and a secret binding polymer.

The pure fish meal has no additives and is an overall better bait, he said. The binder is mixed at a lower rate than that of a traditional patty mixed with clay, making a more concentrated bait. The binder stays keeps the patty together longer than traditional clay too.

Hedrick makes his bait patties to a consistency that allows them to sink without dispersing. He forms balls first, then flattens them to prevent them from rolling around with the current.

“My bait balls look more like hockey pucks,” he said.

Hedrick places two to four patties near each pole, but not too close. Casting will be a problem if patties are too close to the poles. Always place the patties in right-angle directions from the line of poles to keep track of where they are located.

The Net

When the best location is found and the baits are set, the only important factor left is the net.

According to Rourk, “the best net you can throw is the one you can handle and open every time. Tossing a big net halfway open and missing half the bait is a bad combination.”

The minimum legal mesh size is 1/2-inch square, but a larger 5/8-inch mesh is ideal for catching the larger- or smaller-count shrimp. All nets are not created equal. This is easily observed from the range in costs. More expensive nets usually have more weight per inch, allowing the net to sink faster. The larger mesh allows for a faster sink rate, as well.

On the other hand, shallow shrimping really does not require an especially heavy net. Casting a heavy net will quickly fatigue a man. Tailor the net size and weight to the area to be fished to ensure the highest productivity.

Becoming proficient at throwing a cast net is fairly simple and should always occur before the season ever opens. Continuously making fully-open casts every time should be a must while shrimping.

Shrimper productivity

Perfect shrimping conditions vary from region to region. Shrimp are a part of nature and use nature’s signs to determine their movements. Periods of heavy rain or heavy drought during the late summer are poor for fall shrimping. The heavy rain lowers the salinity in the water, forcing the shrimp prematurely into the ocean. Conversely, a long period of drought raises the salinity above the salinity level of the ocean, also forcing the shrimp into the ocean.

Premature migration is bad on the overall shrimp population. Their small size prevents shrimp from evading predators and reduces the capacity of roe for spawning.

“Red/pink legs means that the shrimp are on the move, and this happens when the water temperatures cool down,” Rourk said. Cold spells during the season will force shrimp into deeper holes in the estuaries or completely into the ocean.

Full and new moons also mark the onset of shrimp migration during the season. The lunar pull of the tides causes shrimp to migrate to forward along the travel route towards the ocean.

As shrimp prepare to migrate they begin to feed heavily, and their growth rates are exponential. During the season, shrimp will double in size on a weekly basis; the second half of the season tends to produce the largest shrimp.

Tumbling water temp-eratures cause shrimp and all marine species to move towards their winter hangouts. Shrimp are staging to migrate into the ocean as the water temperatures reach the 60s, and premature or delayed temperature regimes will affect their movements.

Extended periods of cold winter temperatures potentially can wipe out large populations of shrimp that has a delayed affect on fall shrimping. Mild winters, normal rainfall, and seasonal temperatures are the best combination for a successful shrimping season.

Fortunately, the winter of 2006-07 was rather mild, and this fall should produce a bumper crop of shrimp. With the right mix of bait, presentation, and location, S.C. shrimping can offer hot action during the most pleasant months of the fall season.

Be the first to comment