Puppy drum in the evening and flounder gigging at night provide twice the fun at skinny water behind Core Banks.

A light breeze wasn’t enough to blow away a hungry greenhead fly that had attached to my leg, but I was hungry enough to endure its bite long enough to get another mouthful of a juicy burger before swatting the pesky insect.

Hopefully the fly died full and happy.

We were enjoying the seventh-inning stretch of a Core Sound double-header and were grabbing a shore dinner between two kinds of fishing.

We’d already enjoyed several hours of late-afternoon puppy drum fishing; the flounder gigging would begin once the sun disappeared behind Cape Lookout.

Hugh Duncan Sr. of Charlotte had prepared some jumbo burgers at the sound side beach of the small island between Drum Inlet and a new inlet to the south, blown out a few years ago by Hurricane Ophelia. Locals call it, in fact, “Ophelia Inlet.”

Instead of a small charcoal or gas grill, Duncan had an electric griddle he plugged into one of the generators that would power the boat’s flounder lights.

Duncan and Capt. Ray Massengill said the only device needed was a generator with enough capacity to run the griddle. But the 1000-watt models many flounder giggers use to run their lights don’t have enough power to handle the appliances.

The adventure began in mid afternoon after meeting Massengill (Down East Guide Service, 252-671-3474) at the Harkers Island Fishing Center Motel.

His boat, appropriately named The Rig, was loaded and ready for an afternoon and evening of fishing. After stowing cameras, rain gear and a favorite fishing rod in place, we drove a few miles east to Atlantic to launch and explore the shallow waters of Core Sound between the trio of Drum inlets.

The Rig, an aluminum john boat with a small outboard and a fan and motor on a pivoting platform above the outboard, is a unique boat, designed to navigate shallow water.

When the water becomes too shallow for the outboard, Massengill tilts it and fires up the fan motor. Not only does it allow the boat to move freely in water where it’ll float, with no exhaust or propulsion under the water, the fan motor doesn’t scare fish. At this trip it certainly didn’t alarm flounders, red drum, croaker, mullet, multitudes of minnows, skates, crabs or even horseshoe crabs.

Massengill and Duncan are old friends. Duncan was the fabricator of the bracket and steering mechanism for the fan motor. Massengill and I were aboard The Rig while Duncan and Jimmy Miller of Bakersville used Duncan’s jet outboard-powered boat, two shallow-water friendly craft that ultimately served well in the places we sought fish.

Massengill timed the trip so we’d cross Core Sound prior to low tide; we worked our way back to the ramp as the tide was rising. He said it was important for anglers to realize just how shallow the water was at this area.

Once past Core Sound Channel, the area from there to Core Banks is a maze of sandbars, small troughs and sloughs. It’s indeed an area where anglers need to know where they’re going and even then, bottom bumps occur frequently. The local one-liner about Core Sound is “there’s plenty of water in Core Sound; they just spread it out real thin in most places.”

The fact was emphasized at Atlantic’s small private ramp — the basin and parking lot were filled with jet boats and air boats, and every outboard boat had a jack plate.

As we motored away from the ramp, Massengill pointed to Drum Inlet and the south inlet, which can be seen from Atlantic.

The northern inlet is a couple of miles from Drum Inlet and behind a dump island. New inlets created two new islands — the one between Drum Inlet and the south inlet is roughly a half-mile long and flat, while the island between Drum Inlet and the north inlet is roughly 2-miles long and features some dunes and an abandoned structure.

We began by capturing some mullet, tiger and zebra minnows at a slough behind the north island, then we anchored at Drum Inlet to fish.

Bluefish were anxious to take our minnows and cut off several jigs. One barely-legal-but-released flounder came from the inlet, but we wanted puppy drum. Massengill suggested we relocate.

Puppy drum are small drum, from just less than to a little longer than slot size. Opinions vary, but most Down East fishermen say the upper range of “puppy drum” are redfish just below slot to 10 or 15 pounds.

Massengill noted the tide had changed and was running in and suggested we beach the boat on the back of the island and walk the inlet and sound side beach, looking for puppies feeding in sloughs and eddies.

It only took a few minutes and a few more jigs lost to the ravenous bluefish to find a small school of hungry pups. They were holding along the edge of a slough, where a small eddy merged with the tide. It wasn’t a fish-every-cast scenario, but the reds were biting regular enough that no one questioned their presence or hunger.

Most were slot sizes (18 inches to less than 27 inches total length) and loads of fun to catch using speckled-trout tackle.

“I really like catching these puppies,” Massengill said. “Once we find them, they seem to always be hungry and they give you such a battle on this light tackle. They’re healthy fish too and swim away quickly to bite again later.

“Sometimes I wonder if they aren’t so hardy and hungry we might occasionally catch the same fish again on the same day.”

The action was so constant Duncan surprised us by calling out that supper was ready. Massengill checked his watch and gave the “one-last-cast” command, and each angler landed a puppy drum — which was the signal to stop and eat.

In actuality, we needed to hustle because darkness would fall within a few minutes.

The hamburgers really hit the spot, especially loaded with sweet onions and tomatoes from Duncan’s garden. After wolfing them down, we quickly policed our dinner site for trash and readied the boats for flounder gigging.

Duncan had a six-light rig that pivoted up and down on his boat’s bow. He and Miller rotated between driving and gigging.

Because of the multiple purpose needs of The Rig, Massengill had to take a couple of minutes to place his lights on brackets bolted to the bow. However, we were ready just before the last rays of the red sun slipped behind the western horizon.

At a strange area, darkness creates a slightly uneasy feeling that’s amplified by being on water. Exposed sand bars we’d seen while crossing the sound in the afternoon increased that uneasiness. However, we were fortunate to have Massengill, with his back-of-the-hand knowledge of the region and equipment designed for the job to lead our quest.

Lights glowing underwater gave off an eerie glow and were augmented slightly by using fluorescent rather than incandescent lights. Many smaller fish are attracted to the lights and larger fish don’t appear to be particularly alarmed.

The flounder lie in beds and depressions and allow the boat to move right up on them. However, none of them liked the flash of a camera and usually moved away quickly once the shutter snapped.

At first we saw some small fish and several flounder beds, but all were marginal in size. Massengill was adamant that the way to avoid short flounder was to avoid gigging those of questionable sizes.

He said many people have misconceptions about gigs; he insisted gigs actually are selective fishing equipment. He said a gig couldn’t impale a fish the gigger didn’t strike. Problems with selection of fish originate with giggers, not the equipment.

We only attempted pictures of several flounder that may have been slightly longer than the 14-inch minimum. Massengill’s concern was that some fishermen would have gigged these fish then discovered they were barely short. Unfortunately flounder don’t recover well from holes in their heads.

Jim Knight of Southport is a member of the Southern Flounder Fishery Management Plan Committee and agreed with Massengill that a gig can be as selective as the user wants it to be.

However, Knight has concerns with the increasing numbers of flounder giggers, specifically those with less restraint than Massengill. Knight, like Massengill, knows an undersize flounder stuck with a gig will usually die, even if it’s been released.

Knight also has concerns with hook-and-line anglers and netters — commercial and recreational — keeping undersize and/or too many fish. He said N.C.’s flounder numbers are lower than they were several years ago and fears current limits aren’t strict enough to avoid population downturns because of increased fishing effort.

Knight also has recommended conducting more studies about water quality as a possible cause of the reducing numbers and cited the increasing number of flounder being caught at nearshore ocean artificial reefs rather than in the creeks and rivers.

“You should always try to gig flounder in their head,” Massengill said. “This is the best placement for several reasons. Of course one is because it doesn’t poke holes in the meat you came to catch for eating. Another is it tends to disable them more quickly and make it easier to get them into the boat.”

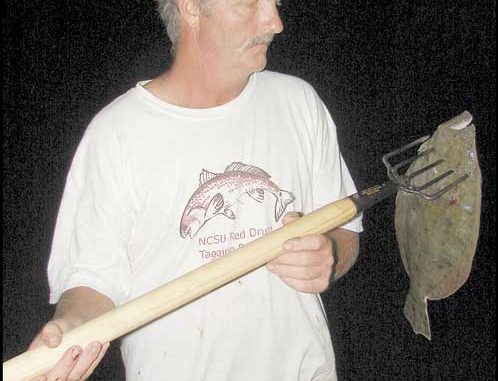

Just as Massengill finished this explanation, a nice flounder appeared at the edge of the lights. The gigger waited until we were near and carefully placed his trident over the fish’s head before striking.

The flounder struggled for a few moments and muddied up the water before it calmed and allowed Massengill to swing it into the boat. Once it was safely in the boat, he opened the cooler and worked it off the gig points, then dropped it into the waiting ice.

“Did you notice anything different about the bottom around that flounder?” Massengill said.

He returned to the spot and offered this explanation.

“Look, the bottom around that flounder was softer and smoother,” Massengill said. “I call it an ‘oatmeal’ bottom because it’s generally smooth and soft and has those scattered depressions like you see in a bowl of oatmeal.

“We find flounder on the rippled bottom we’ve been crossing, but I believe we find more of them and larger ones at the oatmeal bottom. This piece runs for a ways behind the ridge of this shoal, so lets work down it a while and see if they’re here tonight.”

My recognition of distance might have been a little off in the darkness, but it seemed as if we hadn’t gone 20 yards when we came upon another flounder resting in one of the depressions. It was a little to the side and at the edge of the light, and our momentum carried us a little past it.

“Don’t worry,” Massengill said. “He’ll be lying right there once I back up. They don’t usually get alarmed and run unless you bump them or make an unusual noise.”

Sure enough, Massengill used his gig as a push pole to back the boat a few feet. The flounder, now in front of the boat, was still in the depression. Once in position, Massengill readied his gig and drove it home.

After a couple of hours of similar action, the wind began picking up a bit and rippling the water, which made it difficult to see the bottom. We’d already enjoyed a great afternoon and evening and decided to call it a day rather than continue just to say we had filled our limits.

Besides, we had a good mess of flounder in the cooler and would have to spend a little time cleaning them to enjoy the fillets for dinner the next evening.

Be the first to comment