Where are N.C.’s best places to find public- and private-land wild turkeys this spring? You might be surprised.

Residents of the tiny western North Carolina town of Franklin can tell visitors where to find wild turkeys — just go to a local fast-food restaurant.

“About every day two wild gobblers show up at the McDonald’s parking lot,” said Tex Corbin, president of the Nantahala chapter of the N.C. Wild Turkey Federation. “The turkeys hang around, and people feed them french fries and stuff. Then they go on their way.”

Local Macon County citizens, who protect the two wild birds, have named them “Mac” and “Donald.”

Of course, these two turkeys can’t be hunted, but their presence within the town’s city limits is evidence of how much the region’s turkey population has expanded.

About 30 years ago, seeing a wild turkey anywhere in western N.C. was about as common as spotting a passenger pigeon. But during the 1970s, the N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission’s biologists, which began a turkey-restoration program at that time, held out the most hope for this region.

The WRC’s first wild-turkey project leader, the late Wayne Bailey, believed the vast Pisgah and Nantahala national forests, encompassing 1 million acres in western N.C., were the best places for wild turkeys to survive and expand without excessive pressure from men and natural predators. Bailey and his successors, Brian Hyder and Mike Seamster, put most of their early restocking efforts into this part of the state.

Although their work didn’t produce major results for years, they planted seeds that are paying dividends today.

What’s the explanation for the rise in turkey numbers in the west after years of few birds? Evin Stanford, the WRC’s deer-project leader and its new turkey biologist (since November 2007), offered a few answers.

“I don’t consider myself a hard-core turkey biologist yet,” he said, “but I guess at one time, the philosophy of all biologists was wild turkeys needed large blocks of unbroken hardwoods to thrive and wouldn’t do well in broken-up landscapes, especially in the coastal area (of North Carolina) with its pine forests and few stands of hardwoods.

“I think everybody thought restoration would do better in western N.C., with all the national forests and hardwood stands. We learned over time we were wrong about that in some respects.”

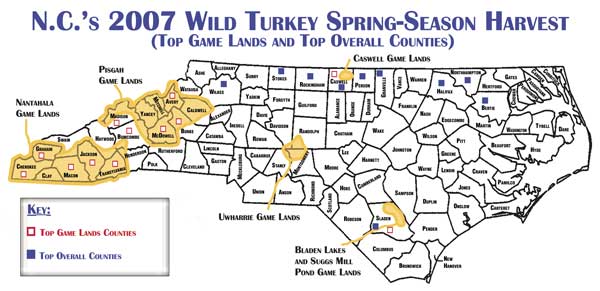

After years of low turkey harvests, western hunters gradually started to bag more gobblers. During 2007, turkey hunters statewide accounted for the second-highest spring gobblers harvest on record (10,082 registered kills), and western N.C.’s game lands led the state by a wide margin. Counties west of the Appalachian foothills accounted for 10 of the top-13 areas for 2007 game-lands turkey harvests, including the top three in the far-western corner.

Hunters at Cherokee County (the Nantahala National Forest) tagged 60 gobblers, which led all N.C. game lands. That total was followed by another Nantahala county, Macon, with 48 gobblers. Nearby Graham County hunters tagged 44 birds. Burke County, which contains South Mountains and Pisgah game lands, saw hunters down 37 spring gobblers. Buncombe County (which contains the city of Asheville and sections of Pisgah land) tallied 30 turkey game-land kills last spring. Jackson and Transylvania counties (in the Nantahala region) had 24 and 22 tagged turkeys, respectively. Madison (22 turkeys), McDowell (19) and Avery (18) counties each contain sections of the Pisgah Game Lands.

The only non-western N.C. game-lands counties to break into the top 13 were Caswell (37 gobblers), Montgomery (26 birds taken at Uwharrie National Forest), and Bladen (22 birds from Bladen Lakes State Forest and Suggs Mill Pond game lands).

“The western part of the state’s turkey harvest is driven by quality habitat,” Stanford said, “and we now realize the (low) estimates made decades ago have been far exceeded.

“There are large blocks of hardwoods areas to hunt in the national forests. And, if you look at the percentage of areas out there to hunt, it’s definitely higher than what’s available in the piedmont and coastal plain.”

Basically, there’s just a lot more game lands acreage to hunt in the west. Stanford pointed out another factor that has allowed western N.C. turkey harvests to rebound.

“There’s just a lot more turkey hunters in the west than in the east,” he said.

Of course, there are major differences in hunting turkeys in the west — hunters have to be in excellent physical condition and a lot of scouting is required because of the vast amount of land where turkeys live in the national forests. Choosing where to hunt can be a daunting task, but Corbin said local hunters have learned where to look.

“It’s a lot different hunting here than Down East or the piedmont,” Corbin said. “It’s a whole lot tougher; it’s basically (hunting) straight up and straight down. The elevation and terrain determines where you’ll hunt.”

Corbin said physical endurance, scouting and finding food sources are keys to turkey-hunting success in the west.

“If there’s a good mast crop from last year in the higher elevations, that’s where you hunt,” he said. “But often you’ll see (birds) at some of the old pastures at lower elevations. In either case, you have to get up high and listen for them to gobble. Once you locate a gobbler, the hunting (approach) is about the same as anywhere else — you try to get above (the turkey) or on the same level. But first you have to go where the turkeys are.”

In order to eliminate land without birds, Corbin said western N.C. hunters don’t wait until just before the season to begin scouting, as is common in the piedmont or east.

“February is the time to start scouting here,” he said. “You need to look for fresh signs (scratchings, droppings) in the woods. If you have some friends who hunt turkeys, that can really help because you can cover more territory.”

Corbin said he primarily hunts U.S. Forest Service (Nantahala) game lands because most private land is broken up into small segments.

“The main thing is courtesy at game lands or Forest Service land because there’s a lot of turkey hunters,” he said. “The game lands have gates, so you have to park and walk. If you see a truck parked at your favorite spot, you go to another place and not walk in on a hunter. If you get there first, the other guys do the same. Most hunters out here understand and are courteous.”

Turkey restoration, centered in the west for years, hit the top of the grade during the 1990s. Flocks have expanded since then, as western hunters regularly report seeing flocks of 50, 60 and even 70 birds.

Fortunately, while the WRC’s turkey restoration kick-started birds in the west, biologists discovered another assumption about requirements for good habitat in the piedmont and east also was incorrect.

“They learned turkeys also do well in broken-up hardwoods and pine forests,” Stanford said. “Turkeys have the ability to populate areas with broken habitat that also have rural segments. It’s allowed turkeys to expand into every county, including the piedmont and east.”

The best places in the piedmont have been the northern tier of counties from Stokes County in the west to Northampton County in the east.

“I’m sure the biologists realized turkeys could do well with some fragmentation of habitat,” Stanford said. “There are lots of such places in the piedmont and coastal plain where turkeys have done surprisingly well.”

Indeed. If a current hunter has access to private land, there’s no better choice than N.C. counties that share a border with Virginia. Many are included in the Roanoke River drainage.

Northampton County, which led all counties in 2007 spring turkeys killed with 333 and has only a small portion of game land, contains mostly rural, private land with large fields and swamps for roosting areas. The Roanoke River flows along its southern border, part of a region containing the turkey-rich Roanoke River Wetlands Game Land.

Rockingham County, north of Greensboro and also bordering Virginia, was second among counties with 325 tagged birds in 2007, while Halifax County, a neighbor of Northampton with similar habitat and Roanoke River Wetlands and National Wildlife Refuge Game Lands areas, was third with 309 gobblers last spring.

Granville County, another northern-tier county, was fourth with 305 harvested birds, followed by Caswell (255 birds), Stokes (284 birds), Bertie (241 birds), Wilkes (218), Person (214) and Bladen (199).

Caswell, a long-time turkey stronghold, also borders Virginia, in addition to Person County.

Bertie County has the largest portion of Roanoke River Wetlands and National Wildlife Refuge Game Lands of the entire state and borders Halifax and Northampton.

Stokes and Wilkes at the northwestern corner of the state are two counties with a tradition of big turkey flocks and hard-core hunters.

Bladen is the only county among the top 10 that isn’t in the northern piedmont. But Bladen is part of the Cape Fear drainage and contains Bladen Lakes State Forest and the Suggs Mill Pond game lands.

Stanford said one reason for smaller turkey harvests in the east is a traditional lack of gobbler hunters.

“I also think turkey restoration was slower coming to the east than other areas,” he said. “Not until the last five years did we start moving a lot of turkeys into the coastal plain. I’ve been an avid turkey hunter for 15 years, but most of the people who live in my region are deer and small-game hunters, not turkey hunters.

“That’s not to say there aren’t some really hard-core turkey hunters in the east; there aren’t as many as at other areas.

“Consider Asheville. Nearly everybody up there hunts turkeys, and they’ve done it for years. In Beaufort County, there’s just not that many people hunting turkeys. Then again, there’s not as many turkeys down here as there are in Buncombe County. (Turkey hunting) just hasn’t caught on as well in the east yet.”

In the central and northern piedmont, which also are strong wild turkey areas, Stanford said even though many northern piedmont counties are dotted by small towns, a lot of the land is rural with a good mix of pastures, hardwood forests and pines. In essence, these regions contain “broken” habitat that wild turkeys find suitable to their needs,

Annual turkey harvests usually are driven by survival of young turkeys during the spring the previous season. Strangely enough, North Carolina has seen three straight years of poor spring reproduction, which is cataloged by the WRC’s annual brood surveys. However, the state’s hunters have experienced two consecutive record spring harvests.

Brood surveys indicate the average number of turkey “poults” (young birds) that survive and are seen with individual turkey hens in the late spring and early summer months. Average brood survival of 3.0 poults per hen is considered outstanding, even though hens usually lay and hatch 10 to 12 eggs each May and June.

“Last year (2007), the brood survey indicated poor reproduction in the west, a little better in the piedmont and the best in the east,” Stanford said.

Brood survival in the west was 1.6 poults, while in the piedmont the number was 1.9, but it increased to 2.3 poults per hen in the east.

“(Brood survival) is probably related to weather factors,” Stanford said. “Last year we had snow in the ground Easter weekend, and that (cold) weather is tough on young turkeys, particularly in the piedmont and west. But the temperatures weren’t as extreme in the east.

“You can have just one major weather event, a late snow or heavy rain, and it can affect the survival of young turkeys.”

Stanford also said extended periods of cold weather can cause turkey eggs to lose their viability.

“Poults born in those conditions often die,” he said. “(Bad weather) also makes it tough for hens to meet their own biological needs. But the main problem is hypothermia. If there’s extended cold rains, and turkey chicks are covered with down, not old enough to have feathers, they’ll get soaked. Hypothermia (low body temperature) sets in and kills them.”

Stanford said ideal brooding conditions for hens and young turkeys include moderate temperatures and little rainfall during the spring, especially no heavy or extended rainfalls of 2 to 3 inches.

“If there’s a relatively dry spring and a good mast crop, turkeys do better,” he said.

Stanford’s expectations for the 2008 spring season aren’t great, precisely because of two straight springs marked by bad weather and poor poult survival.

“Most hunters kill 2-year-old gobblers,” Stanford said, “because they gobble more.”

But with two years of poor summer brood survival, N.C.’s 2008 harvest might fall below 10,000 gobblers because fewer 2-year-old birds may have survived in 2006. Turkeys born that summer would have been the 2-year-old birds hunters would hear gobbling this spring.

“(The potential 2008 harvest) actually isn’t really encouraging,” Stanford said, “because of the back-to-back poor-to-fair hatches, particularly in the west and piedmont.”

Stanford said the best opportunities to take a gobbler in 2008 may be in the east.

“Last year the (brood surveys) generally were better moving to the east,” he said, “and it was similar in 2006.”

One saving grace for western N.C. hunters who have a tough time seeing a bird this spring could be a visit to McDonald’s in Franklin. But they’ll have to remember only to bring a camera to take photos of Mac and Donald, the two gobblers who like french fries.

Be the first to comment