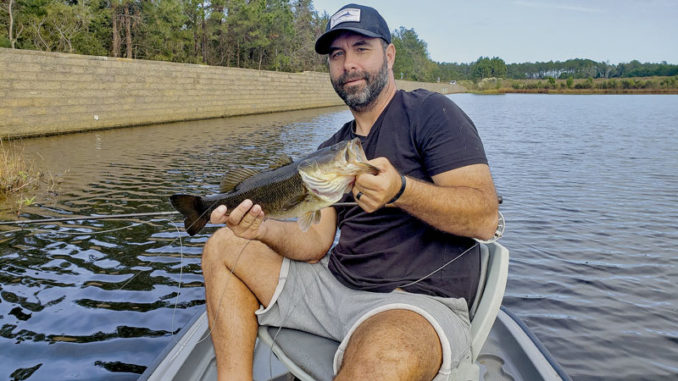

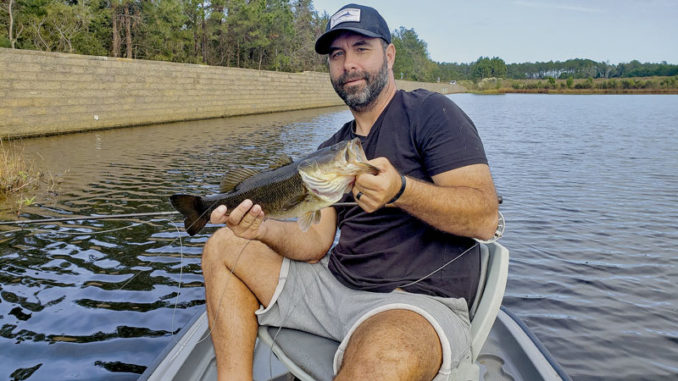

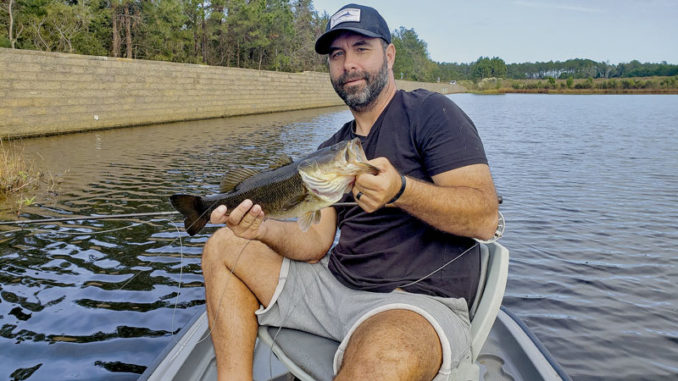

Fly-rod bass fishing is a great summer technique

A lot of controversy surrounds North Carolina’s flounder fishery. Will it get any better? […]

Here’s a look at the Pechmann Center’s fishing course schedule for May 2024. […]

Copyright 1999 - 2024 Carolina Sportsman, Inc. All rights reserved.

Be the first to comment