Searching for a summertime Tarpon Hotspot?

Leaping and bounding from wave to wave at lightening speed fits the profile for a phenomenal hookup with the elusive top predator and coveted sportfish of South Carolina’s waters. There is no need to travel to the Sunshine State to battle the elusive silver king; South Carolina’s coastal estuaries and inlets are prime locales to hook up with a mature, trophy tarpon.

Anglers beware: the spectacular runs of a big tarpon brutally test a fisherman’s strength and endurance, as well as the integrity of every knot and connective point on any rod and reel combination available.

Despite their popularity, most of the aspects of tarpons’ migration and lifestyle remain a mystery. They are elusive predators who spend most of the year in the super-heated, tropical waters of the south. The reason for their travel patterns is only partially known. Fish tagged and released in South Carolina have showed up in Florida’s keys one year and the northernmost reaches of the Gulf of Mexico the next.

The little research that has been done reveals a few details about their travel patterns. Tarpon school up in late spring and early summer as they prepare to spawn offshore. Afterwards, the tarpon larvae drift with the currents and tides into inshore lagoons and swamps to mature.

Adults travel back towards shore in small schools and scatter throughout coastal regions, looking for large schools of migrating baitfish traveling up the coastline into regions as far north as Virginia. Tarpon cannot tolerate cool water temperatures and will travel back to the tropics as fall progresses.

Since tarpon are strictly carnivorous, opportunistic feeders, preying mostly on mullet, menhaden, croaker, spot, shrimp, and crabs, the Georgetown area’s inlets and bays offer plenty of feeding opportunities. Only adult tarpon make the annual trek north, allowing fishermen to count on the tarpon found in South Carolina waters to be trophies weighing anywhere from 45 to 200 pounds.

Tarpon first begin to arrive along the South Carolina coast in June. They will concentrate as the summer progresses to early fall, when gargantuan schools of striped mullet arrive on their fall migration. They’ll stay until the first cold snap, which will send them southward.

Locating the fish

Capt. Tommy Scarborough of Georgetown Coastal Adventures has a handle on where and when tarpon will show up in his area.

“Tarpon movement is dictated by the movement of large schools of bait. As the large schools of menhaden start showing up in June, so do the tarpon,” said Scarborough, who has trophy silver kings land in one of his boats every year — despite not targeting them regularly.

The tarpon’s ultimate Achilles heel is its willingness to surface frequently to gulp air, and its eagerness to show off like a Hollywood celebrity.

“Tarpon don’t hide very well when they are around,” Scarborough said. “They start rolling and gulping air, revealing their presence for all to see. If tarpon are in the area, they will show themselves.”

Tarpon gulp air to run oxygen through their swim bladders. They are thought to be prehistoric sea creatures that have lived in the Atlantic Ocean for more then 125 million years.

They will increase their air-gulping behavior when the dissolved oxygen content in the water is low and when they exert extra energy before or after feeding periods.

As with any other top predator, tarpon almost always stay close to large schools of bait. Find the bait, and the tarpon will be close behind. However, since bait is overly abundant in the Georgetown area, a game of “cat and mouse” faces the fisherman. The search can be endless, but luckily, tarpon frequent the same areas annually, reducing the search time.

Inlets, shoals, drastic depth changes, and structure create current rips as tides roll in and out. The rips congregate the bait and provide an ambush point for tarpon.

“Saltwater structure outside the inlets is a wall of water created by currents,” Scarborough said.

As the water warms and large schools of bait arrive, Scarborough starts looking for the flash of tarpon rolling in schools of bait within bays and along beachfronts. Just as the experienced king mackerel fisherman knows where to find bait at the crack of dawn, Scarborough’s primary tactic is “running and gunning” — looking for surfacing fish within the large schools of bait.

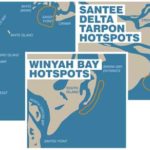

Scarborough’s favorite hideout for tarpon is from the south jetty at Georgetown, a half-mile off the beach all the way to the mouth of the North Santee River, where the water is cloudy. Bait stacks up there late in the summer, and it is a prime location for tarpon.

“I look for clear pockets in the schools of bait — where the pods are broken up. Predator fish cut the pods of bait, gobbling up a few along the way,” Scarborough said.

He stops, shuts off his outboard motor and sits for five to 10 minutes, looking for surfacing fish. If none show themselves, he continues to run the coastline line, looking.

Tarpon will follow pods of bait into shallow bays, including the Intracoastal Waterway, but Scarborough generally restricts his search from the just outside the jetties on the ocean side to up the rivers as far inland as the Rt. 17 bridge.

As the tide fluctuates, timing is everything. Topography, structure, and strength of the tide creates intense current rips, bunching up pods of bait fish. While these opportunities may only be brief, they provide a great chance to see a tarpon.

Scarborough will arrive at these locations and set up 30 minutes before the rips form and intensify. He will stay for an hour or so in hopes of a hook-up. If he’s unsuccessful, he moves to another area that features similar conditions.

Scarborough chases tarpon from North Inlet all the way to Bulls Bay. Some of his favorite locations in the Bulls Bay/Cape Romain area are the hole at Bull Island next to the shoal and the hole southeast of the White Banks. Both the inlets at the mouth of the North Santee and South Santee rivers are good locations, as well as off the beach in both directions, plus several miles upriver towards the ICW.

The shoals in North Inlet and several areas scattered throughout Muddy Bay adjacent to the river channel are good places to find tarpon surfacing.

Over the years, Scarborough has understand the importance of networking with commercial fishermen in the area, because there are hundreds of places tarpon may show up.

“My crabbing buddies call me when they see a school of tarpon gulping air,” Scarborough said.

Trying to locate schooling tarpon brings on a level of frustration shared by many tarpon fanatics in the south, including Capt. Gene Dickson of Delta Guide Service. With more than 25 years of professional experience in the Georgetown area, his is the longest-operating guide service in the region. He concentrates his efforts in the same areas that Scarborough frequents, where the bait congregates adjacent to deeper waters near the ocean.

“Any underwater object large enough to disrupt water flow will cause baitfish to concentrate. Objects such as sand bars near the mouth of inlets, rock jetties, and natural channels are good places to look,” Dickson said.

Tide lines are excellent places to find tarpon surfacing. Dickson looks for areas where the falling tide brings the darker, brackish river water up against the green ocean water just inside or outside the inlet. Swarms of baitfish and predators alike gang up to eat and be eaten.

Tarpon are spooky and dislike the unnatural sounds of marine engines; they will stop feeding if uncomfortable. Dickson makes every effort to reduce to noise when entering a hot tarpon spot by drifting or using an electric trolling motor.

He concentrates around the larger inlets such as North Inlet, Key Inlet, the Winyah Bay jetties, North Santee Bay, and South Santee Bay. He also fishes around the entrance to Cape Romain Harbor and Cape Romain itself around the nearshore sandbars, and the north point of Bull Island.

Setting up shop

Tarpon will feed throughout the water column. Scarborough fishes several lines on the bottom and several closer to the surface under floats. For his surface lines, he leaves 10 to 12 feet of leader under the cork with no weight, allowing the baitfish to swim freely. His bottom rigs utilize a sinker with five feet of 80- to 100-pound fluorocarbon leader. He generally uses Owner 5/0 J-hooks, but he will use 10/0 to 13/0 circle hooks on occasion. He prefers the smaller hooks because they keep the bait lively. The heavier hooks cut down the action of the bait, reducing chances for a hookup.

Live bait is prime for tarpon. Early in the season, Scarbor-ough will use the largest menhaden available. As soon as the striped mullet show up, he switches over to 6- to 10-inch mullet, but will not use any bait much heavier than a pound. When croakers are available, Scarbor-ough trades the menhaden and mullet for some lively 6- to 8-inch croakers.

“If tarpon are surfacing, and I have live croakers in the set, I tell my clients to look out. Croakers are absolutely deadly for tarpon,” he said.

Dickson prefers live bait 10-to-1 over dead bait, but he has caught many tarpon on fresh dead bait when live bait was not available.

While chumming is the “norm” for luring many top gamefish, neither Scarborough nor Dickson will chum while tarpon fishing. According to Scarborough, chumming is the “kiss of death” — attracting every shark in the ocean.

Both Scarborough and Dickson agree that tarpon are very leery of unnatural noises.

“Getting the lines as far from the boat as possible will yield in a better opportunity for a hook up,” Scarborough said.

As long as the wind and currents allow, he sets out a kite rig and floats a bait just off the surface well behind the boat. At times, when tarpon are in the area but are scattered, Scarborough will drift through schools of bait as well.

If croakers are available, he will butterfly them, removing the backbone. The slow pull causes it to undulate from side to side, drawing fish from afar.

Seeing tarpon and catching tarpon are two different things. While they feed throughout the day, they usually feed more at dawn and dusk. However, even when lively baits are swimming within 50 to 100 yards of a lurking tarpon, a hook-up isn’t a sure thing. Tarpon are very sensitive to unnatural feelings. As a tarpon engulfs a bait, it feels the point of the hook and tension of the line. They erupt almost immediately, breaking the surface, shaking their head from side to side trying to shake the hook. Fishermen usually sees the fish jump before they realize there has been a hook-up. Unfortunately, tarpon have a thick, bony mouth, and hooks must be ultra-sharp to penetrate and set beyond the barb.

Tarpon frequenting South Carolina’s waters are known for their quick, long runs that can spool high-capacity reels. Scarborough uses Tryon 66 baitcasters with 250 yards of 30-pound Berkeley Fireline rigged on a 6½-foot Shakespeare Tigerlite medium/heavy rod. He recommends tying a polyball to the anchor line, allowing for a quick release to chase a fleeing fish. Soon as the fish realize the hook is lodged, it will head out to sea. Strong tackle is a must and should be inspected frequently.

Dickson fishes with fairly heavy tackle: a stiff 7-foot rod with roller leads as well, with at least 250 pounds of 30-pound test mono for added line stretch. He stresses the need for extremely sharp hooks.

“You need the hooks to be so sharp that they hurt your eyes to look at them, and that’s just barely sharp enough,” he said.

Dickson’s standard tarpon rig is made up of a black, 150-pound-test swivel tied to about three feet of 50-pound test Berkley Big Game and a razor-sharp, black 8/0 circle hook. Tie to the swivel, in the same eye as the main line, about a foot of 10-pound test mono to which is tied a 1-ounce bank sinker. It will break free as soon as the tarpon starts his violent head shaking.

Be the first to comment