Swansboro sheepshead anglers find a comfort zone and cool fishing under bridges that never are too far.

Capt. Jeff Cronk is one of the most energetic fishermen along the coast of North Carolina. A high school math teacher, he still finds a way to take clients fishing more than 120 days per year. He guides evenings, weekends and vacation breaks and knows his home waters of Swansboro better than most people know their backyards.

“It’s hot today, and it looks like the weatherman is going to throw us a thunderstorm, so let’s go sheepshead fishing,” Cronk said aboard his Triton center console at Dudley’s Marina.

While someone would think an angler as high-powered as Cronk would want to head offshore for Swansboro’s blistering runs of king mackerel or arm-wrenching runs of big-shouldered red drum, he picked a trip for sheepshead.

It was no breakneck run to his sheepshead hole beneath the N.C. 24 Bridge. In fact, it was an idle-speed trip. At the end of the short boat ride, Cronk had it made in the shade.

As he left the scorching sunlight and ominous, cumulus clouds building like thundering mountains from the southwest, a sense of serenity and secrecy closed like a curtain beneath the shadow of the bridge.

Other anglers pulled up alongside the concrete bridge pilings. Everyone waved to Cronk and told him whether or not they were catching sheepshead.

“I know everyone under the bridge,” he said. “Those folks over there are clients from Raleigh who fished with me yesterday. The whole family caught fish, and they’re back for more. I love it when there are kids along because catching sheepshead is a perfect kids’ trip.”

Cronk pulled near a piling and placed an old raincoat between the concrete and the boat gunwale to protect the gel coat on the boat’s fiberglass. He tied off to the piling fore and aft and raked the hook of his gaff up and down along the encrusted barnacles and oyster shells on the concrete below the tide line.

“It’s ready-made chum when you expose the meat inside the shells,” he said. “When the tide comes up, the sheepshead smell it and are attracted to your bait fished right beside it. Sometimes I can even spot the fish before I start fishing. See, there’s a big one now.”

Protected from the glare of the sun by the bridge, the water became transparent. It was easy to see several feet beneath the surface. A big sheepshead was swimming slowly with its head pointed toward the piling, nibbling away at the encrustations like a kid munching away at corn on the cob.

“You hear everyone telling you how a sheepshead bite is so subtle,” Cronk said. “But it’s really like almost any other fish. They snip the bait off the hook. But when they get the hook in their mouth, you can feel it. Sometimes when conditions are like this, you can see them eat the bait.

“When they do, you just set the hook and the fight is on.”

Cronk had impaled a fiddler crab on his hook and dropped it down to the sheepshead he could see feeding. Before he said another word, he hauled back on the rod to set the hook.

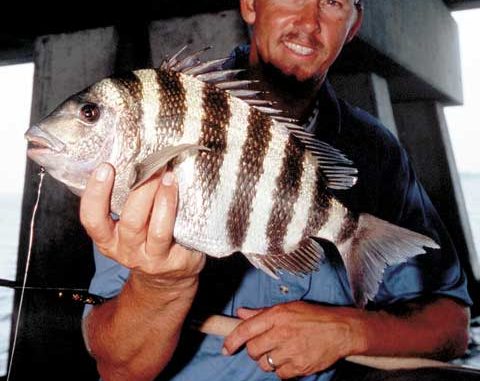

After a powerful struggle, which was as he described it, “like catching a bream on steroids” he scooped a sheepshead of about 3 pounds from the water with a wide, deep landing net.

“When you hook a big one like that, you have to use a net,” he said. “You’re playing the fish so close to the pilings, any surge and he’s going to hit something sharp with the line and cut it off. With the little ones under a pound in weight, you just swing them into the boat.”

Cronk was fishing the western N.C. 24 Bridge at Swansboro. He said the eastern N.C. 24 Bridge was too low for fishing from a boat with a T-top. He also fishes the N.C. 58 Bridge to Emerald Isle from the mainland. But multiple boat wakes make the fishing there difficult during weekends.

“You can catch sheepshead under the bridges anytime from May through October,” he said. “But the fishing is really good in June and July, and it’s nice to get away from the heat or the weather.

“Listen to the thunder. Look at all the boats heading in. Here we sit, out of the rain and wind catching some of the best-eating fish, hardest-fighting fish in the water.”

Cronk catches his baits — fiddler crabs — but they also can be bought at bait-and-tackle shops. He cruises the marshes during the last half of the falling tide when fiddlers come out to feed and mate and move away from their holes to the edges.

“I run about 50 yards away until I spot a swarm of them,” he said. “I get out of the boat and walk into the grass then come out of the marsh behind them to catch them when they are in between the water and the grass. I use the same menhaden dip net I use in my live well and just scoop up as many as I need and put them in a plastic bucket.

“They live for a long time if you keep them out of the sun. What you don’t want to do is turn the bucket over in the boat by accident or you’ll be crunching fiddlers underfoot for a week.”

It takes lots of fiddlers to make a successful sheepshead outing. Cronk said an angler could get 50 bites an hour and land 10 fish. With three anglers fishing, that’s 150 baits gone per hour.

“Most beginners start fishing with too few baits,” he said. “They get frustrated with all the little sheepshead and other bait-stealers and give up. The most important thing is having enough bait.”

Cronk also catches mud crabs by looking over the marina pilings. He can pull the crabs from between the oyster shells at low tide using needle-nose pliers. Anglers also catch them by turning over and rocks at low tide. Mud crabs are hiding anywhere there are oyster shells, which is a nice tidbit of information for anyone who runs out of sheepshead bait while fishing bridge pilings.

“If you’re getting little pecks and bring in the bait with only the legs missing there are probably pinfish or spadefish biting,” Cronk said. “A small sheepshead might make a clean bite through the shell or just snip the whole crab from the hook without you feeling it.”

Cronk fishes for sheepshead with a Carolina rig. He uses a stout, steel 1/0 live bait hook and 2 feet of 40-pound fluorocarbon leader. The leader is stiff enough to transmit the sensation of a strike through the 14-pound Berkley Fireline superbraid line he uses on his spinning reels. For weight he uses a large split shot, sometimes increasing the weight to a ½-ounce or 1-ounce egg sinker if the current is strong.

“I use Fireline because I can feel the strike better than I could with mono,” he said. “Fluorocarbon leader is also better than mono. Besides being stiffer for better feel, it can withstand the inevitable nicks you’re going to get from the pilings better than mono. If you nick a mono leader, it breaks much easier than a fluorocarbon leader.”

Hooking a crab is an art among successful sheepshead fishermen. Cronk inserts the hook through the leg openings in the side of the carapace and out the rear of the shell. He pushes the hook through slowly to keep the shell from cracking and allows the hook point to barely protrude from the shell.

“You have to support the body with your fingers while inserting the hook so the shell won’t crack,” he said. “You also have to be careful because fiddler crabs can nip you with their pincers hard enough to draw blood. It sounds funny until you’ve felt it. Any marine wound can easily become infected, so it pays to be careful.

“When you pick up a male fiddler, hold it by the big claw or pinch the body so he can’t get you. The female’s claws are too small to be a threat. You can also dump them in ice so they get lethargic for easier handling if kids are along.”

A big sheepshead weighs 6 to 8 pounds. When Cronk is fishing for these trophy-sized fish, he nearly always sight fishes.

“You motor along from piling to piling and spot their backs sticking out of the water,” he said. “A big sheepshead is likely to stay in the same spot for a long time, so it gives you a chance at him.

“He may move off when you try to tie up. But he usually comes back. You can chum with crushed fiddlers or by scraping pilings. I like to fish the moving water stages of the tide, letting the current bring the fish to the scent.”

A big sheepshead bites a couple of times, crunching up the fiddler. Cronk isn’t as fast on the trigger as many sheepshead anglers when fishing for the big ones. He said he catches a 5- to 10-pound sheepshead every day if there’s a strong bite.

“I wait until I feel the thump before setting the hook,” he said. “If it’s a small one, it’s more of a nibbling sensation. But I still don’t set the hook until I feel the fish taking the rod down. It’s sometimes more visible than a felt strike because you are actually watching the rod tip move downward.”

There are lots of things to hang the hook besides the insides of a sheepshead’s toothy kisser. Since you are fishing right beside the pilings, the current or a fish can take the hook right into the shells.

“You may hook an oyster shell or could get luckier and hang a sea squirt,” Cronk said. “If you hook a sea squirt, you can give it a hard pull and bring the sea squirt in with the hook. But you will also cut or break the line a few times each day when you’re fishing.”

Sooner or later, the odds are with the fishermen and a solid hookup results from a strike. The sheepshead may make a dash for the structure.

“I usually fish from the bow or stern,” Cronk said. “When I hook a sheepshead, I immediately move around to the opposite side of the boat to get away from the pilings.

“I fish a tight drag — around 10 pounds. I want to control the fish. But I have to use some drag or the fish will break the line. But if I’m fishing in the middle of the boat, between the side of the boat and the piling, I lock the drag down and hope the fish gives up before the line does.

“If you have the boat tied off on both sides of you, you don’t have any way of getting that fish to the open water. You have to horse him in.”

The distance between the pilings is only 4 to 6 feet so there’s not much room to play a sheepshead. If he gets between them, he’s gone. That’s why keeping a net handy is mandatory.

“Timing with the net is everything,” he said. “If your net is hung on something in the boat or you can’t get to it quickly, you’re going to lose the fish. He comes up, gives you a shot with the net, and if you miss him, he’s heading for the pilings again. If he goes too deep and gets around them, the fight is over.”

Cronk’s tips for catching sheepshead included advice about water clarity.

Thunderstorms actually help bridge fishing.

“If the water is clear, the sheepshead move upriver to the shell beds,” he said. “But if the water is dingy from the rain, you’re more likely to find them at the bridges.

“When they’re upstream in the White Oak River, I use float rigs to drift fiddlers above the oyster beds at the grass flats. A rising tide and clear water are the best conditions.

“Just cast the float upstream and bring it back toward the shell bed slowly. These will be bigger fish than at the bridges, and they are tough to land because of the shells.

“But it’s always nicer when it’s hot, and they’re at the bridges. That’s when sheepshead anglers have it made in the shade.”

Be the first to comment