When the mercury tumbles, a few Charlotte anglers don’t get moody — they head out for trophy blues.

There are fishermen at Lake Norman who blame the N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission for everything they perceive that’s lacking in the lake.

The stripers and the bass aren’t big enough; there isn’t enough bait; the WRC isn’t doing anything to help. It’s their version of the “Lake Norman Blues.”

However, if you could turn another group of anglers into singers, they’d pound out the praises of Norman’s blues. They probably go to sleep at night saying silent prayers of thanks to the biologists who decided, more than 35 years ago, to stock blue catfish in the 32,500-acre lake on the Catawba River north of Charlotte.

Scott Van Horn wasn’t setting trap nets and running an electro-shocking boat back then, but the fisheries biologist who was for years in charge of North Carolina’s reservoir fisheries has proof in the form of stocking records.

“We stocked some blue catfish in the Cape Fear River and in the Catawba,” he said. “I know we put some in the Catawba system. We put 4,000 in Lake Norman in 1969.

“But nobody heard from ’em for about two decades – nobody had seen a blue catfish, then all of the sudden, they showed up.

“What’s happening now is that the opportunity to catch them has spread, and they’ve gotten more popular with a segment of the angling population.”

Count Chris Nichols of Gastonia as part of that segment. Nichols has become one of the No. 1 fans of the big blue catfish that swim in Lake Norman. For the better part of three or four months during the winter, about the only thing he does in his bass boat is hunt for 10-, 15- and 20-pound blues that seem to wake up and eat everything in sight once the mercury heads toward the bottom of the thermometer.

Nichols works for Carolinas Fishing Guide Service, and most of his winter trips aim to put big blues in the cooler for fishermen. More often than not, he and partner Jerry Neeley of Bessemer City succeed, in part because the catfish are consistent in their location and movements — and they always seem to be hungry.

“The blue catfish in Lake Norman, they’ll bite good all winter,” said Nichols (704-868-2298). “They tend to stack up in certain places, so instead of them being scattered out, the winter weather tends to bunch ’em up. And the colder water tends to compact the baitfish — primarily on the lower end of the lake.

“When you put a concentration of fish in some pretty predictable locations, it makes ’em almost easy to catch.”

Well, easy as long as you understand the fish and what niche it occupies in the lake that has been called by many frustrated fishermen “the great dead sea.”

Blue catfish are the guys who stand at the head of the buffet line and rub their hands together, expectantly because there’s not a thing they see that they don’t like to eat.

Unlike flatheads, their mud-colored cousins, blues aren’t picky. They’ll hit live bait; they’ll hit dead bait; they’ll hit cut bait. And they’ll grow just about as big as those ugly yellow flatheads, with steel-blue sides that almost make them a “pretty” fish.

“Blue catfish are generalists; they’ll eat a lot of different things,” biologist Van Horn said. “You can always find ’em because they’re not too picky.

“You can put ’em just about anywhere, and they’ll do okay. As they’ve gotten more popular, guys are moving ’em around, and pretty soon it will be hard to find a place that doesn’t have blue catfish.

“And it really is the case that blue catfish are pretty much a year-round resource. You can catch (flatheads and channel cats) in the winter, but it’s sort of acknowledged now that blues are as good a winter fishery as stripers are.”

Like a lot of fishermen, Van Horn stumbled onto the fabulous fishery for blue cats at Lake Norman in the late 1990s.

“Five or six or seven years ago, I had a project going with the (biologists) from Duke Power, trying to keep track of stripers’ growth rates and body conditions, and they set up something like 300 feet of net in the state-park area and around those islands in the upper end of the lake,” he said. “When we checked the nets, we had something like 300 blue cats – one for about every foot of net. They weighed from 2 to 25 pounds, and that net was all wrapped up. I think they had to throw it away.”

Why have blue catfish thrived at Lake Norman – the state-record 85-pound fish was caught there in November 2004 – when most other gamefish are behind other lakes in terms of growth rates and overall potential?

It’s matter of them utilizing a food source that few other fish notice: freshwater mussels that thrive by filtering the nutrients out of the lake’s waters. For eight months a year, Norman’s blue cats don’t compete with stripers, largemouth bass, crappie, bluegills, channel cats, white bass, white perch or flathead catfish for the lake’s limited shad and herring forage base – they eat mussels almost all year long, except during the winter.

“At Lake Norman, part of their success is that they’re competing better; they’re exploiting the freshwater Asiatic clams or mussels,” Van Horn said. “If you look at their body condition, they’re not as healthy in Lake Norman as in some other places, but they’re still healthy fish.

“If you cut a striper open at Lake Norman, you find shad. If you cut a (blue) catfish open, you’ll find a lot of things, but especially those corbicula, the freshwater mussels.”

But in the winter, Nichols’ strategy has a lot more to do with shad than mussels.

In the winter, Nichols said that baitfish tend to migrate to the lower end of Lake Norman – downstream from the Rt. 150 bridge. They’re naturally drawn to the warm waters of the “hot hole” discharge from the Marshall Steam Station just west of the bridge, but they tend to fill up the deeper channels at the lower end.

“Davidson Creek, Reeds Creek, Mountain Creek, Lucky Creek and Ramsey Creek — the major creeks below the 150 bridge are gonna hold a lot of catfish, because a lot of baitfish orient on the lower end, especially in deep water,” Nichols said. “And blues are more active in cold weather than other catfish. They’ll definitely feed the whole winter, primarily in big schools and primarily on shad.

“They’ll school up where baitfish are schooled up, because during the winter, a lot of baitfish die off. There’s definitely a period when the shad are dying off from the cold weather, and when that happens, those catfish lay down on the bottom and the shad (drift) down to them, and they put on a lot of weight.

“I think they feed on the mussels most of the year; I don’t know why they quit in the winter, unless it’s because the shad are dying.

“In summer, if you catch one and keep him, his stomach will be slap full of mussels. But in the winter, it’s hard to find one with mussels in him — they’re full of shad.”

So Nichols primarily uses shad, dead shad. He catches them, freezes them, and thaws them out before his fishing trips. He supplements them with fillets from crappie and bream he’s caught with rod and reel (that’s the only way it’s legal), but it’s primarily shad.

Nichols hooks whole dead shad, bream or crappie fillets, or cut pieces of shad on a 2/0 Eagle Claw No. 42 live-bait hook that’s tied to a 2- to 3-foot long leader of 30- to 50-pound Berkley Big Game mono. That’s tied to one end of a barrel swivel, the other end of which he ties to his running line: 17- to 20-pound-test Bass Pro Shops Offshore Angler Tight Line mono, which is bright yellow.

Above the swivel, he slides on a “slinky” weight — a section of nylon parachute cord filled with 12 to 16 pieces of No. 4 buckshot — and all of it is tied to an Abu-Garcia 6500 bait-casting reel and 7-foot medium-action Ugly Stick rod.

“I use a pretty light-action rod, because if you use a rod that’s too heavy, that has a medium-heavy or heavy tip, when the fish pulls on the bait, he’ll feel the tension and spit out the bait,” Nichols said. “With an Ugly Stick, with that (fiber)glass tip, a fish can take the bait a couple of seconds before he feels it, and by that time, he’s already swallowed the bait.”

So, with the right kind of bait and tackle, what are the right kinds of places to catch Lake Norman’s big blues?

“Typically, most of the fish you’re going to catch are going to be at least 15 feet deep — depending on the weather,” Nichols said. “A good average rule of thumb is, you fish about 15 feet deep when the fish are biting real good. But you when you’ve got bluebird skies, when it’s really cold, and the bite is a little slower, you’re going to have to get out and fish deeper.

“I learned last year that a lot of fish will get really deep in this lake, 50 feet or more. It’s not unusual to get out to 50 feet when you’re fishing some of the creek channels and the river channel.”

What Nichols likes to do is check the wind direction and look for creek channels that will allow him to make long, downwind drifts, his baits bouncing off the bottom in a spread of four to six rods.

“I always try to drift with the wind, and I’ve started using my GPS more this year to monitor the speed of my drifts,” he said. “I’m drifting between .7 and 1.1 miles per hour, mostly from .7 to .9.

“I think catfish will always be facing the direction of the wind, because the wind causes the current. You present the bait in front of the fish, and that’s more natural. So I’ll check the wind direction and look at my map and try to set up a drift that fits. And if it gets too rough, you can put out a windsock behind the boat. That’s a valuable tool because not only does it slow the boat down, but it keeps it under control.”

On cloudy days, he tries that 15- to 20-foot water first. If it’s a blustery, bluebird day, he figures on fish being deeper. And he adjusts his tackle accordingly.

“When fish are 15 to 25 feet deep, I’ll use a ¾-ounce or 1-ounce Slinky weight. When they’re more than 25-feet deep, it doesn’t hurt to go to a 1-1/4- or 1-1/2-ounce weight,” Nichols said. “You try to use as light a weight as you can get by with, but on windy days or when they’re in deep water, you need to use the heavier weight to keep the bait near the bottom.

“The other thing is, when the bite is good, I’ll use a whole dead shad. That’s when you can pull bigger baits. When the bite is slower, sometimes they won’t take a big 5-inch gizzard shad. That’s when you’re better off going with a smaller crappie or bream filet, or cutting a shad in three or four pieces.

“Some days when the bite is good, when fronts are moving through and the fish move deep, you use smaller baits. And even a 15- or 20-pound catfish – you can catch him on a small piece of bait.”

Nichols uses the bright yellow monofilament because it’s easier to see when he’s got six baits drifting behind his boat.

“Most of the time, fish will be concentrated, schooled up, and when you find a school, you can go back through it several times,” he said. “When you’re pulling a lot of lines, that visible yellow color allows you to keep them from getting tangled up, and when you’ve got two or three guys winding in fish at once, things can get crazy.”

Finding a creek filled with active fish is almost a guarantee of a big day.

“Every time you drift through a place like that, you’ll catch one or two fish, then you go drift it again and catch one or two more, then do it again,” he said.

Nichols doesn’t totally ignore the “hot hole,” where warm water is discharged from Duke Power’s Marshall Steam Station just downstream from the Rt. 150 bridge on the Catawba County side of the lake. He also pays attention to the back end of creeks when the water gets relatively stained or dirty because of heavy rains or winds

“You can fish in the hot hole in the winter,” he said.”There will be a lot of baitfish in there and a lot of stripers.

“Another thing is, if you find some dingy water, fish will be more shallow. If you have a hard rain, that will move fish up in the shallows – from 6 to 10 feet of water. That can be a good pattern, and you can really catch some big fish doing that.”

Nichols expects fish in the 5- to 10-pound class to make up most of his catch, but in the winter, the chances of doing battle with a real line-stripper are great.

“The quality of the fish we catch depends on the time of year,” he said. “During the summer, you can catch a lot of small fish, but in the winter, you catch a lot of fish in the 5- to 15-pound class.

“You catch a lot of 8- and 9- and 10-pound fish, and you’ll occasionally catch a fish in the 15- to 20-pound range. There’s a good chance of that happening on any given trip. Anything over 25 or 30 is a real trophy.

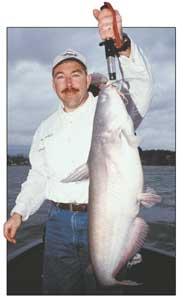

“These catfish are beautiful fish, extremely healthy. One thing about Lake Norman is, the blues are fat, pretty fish. You can’t catch a prettier fish than a nice blue from Lake Norman.”

Be the first to comment