Duck hunting at Cedar Island is a unique experience, but when the weather’s rough, the shooting can be fantastic.

The wind was howling and spitting rain, which was on the edge of turning to sleet.

While most folks with any sense snuggled their shoulders deeper into a nest of bedcovers, we jumped up at the alarm clock.

“Duck hunters are crazy,” Basil Watts said. “Nobody in his right mind would go out in this weather. You reckon our guide will want to go today?”

At the Driftwood Motel’s restaurant, the breakfast buffet was overflowing with duck hunters who were meeting guides. Nearly everyone was in a festive mood, but some of the first-timers displayed apprehension.

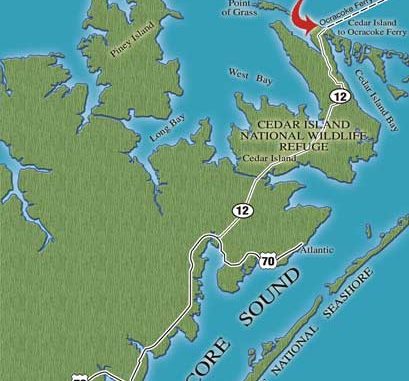

The Pamlico Sound north and east of Cedar Island is huge. It appears to be at the end of the world, except it’s the jumping-off point for the N. C. Department of Transportation’s Cedar-Island-to-Ocracoke ferry and has a N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission boating access area beside the ferry parking lot. And, of course, there’s the historic Driftwood.

The sound is so vast the other side can’t be seen from Cedar Island. But a few duck blinds are scattered across the sand bars of the sound. One of those blinds would be ours for the day.

To local residents, it’s not lands’ end; the sound is home.

“If you want a good hunt, you need to go with Scott Goodwin,” said Capt. Charles Brown of Brown’s Hunting Guide Service. “I really love to shoot those blackheads. But you should be ready for redheads, canvasback, ruddy ducks and whatever else comes into the decoys.

“Take some No. 2 steel or some tungsten shells. Those Cedar Island ducks can be tough, and you have to kill them outright. You don’t want to have to try to chase down a crippled diver when the wind is blowing. You’ll never catch him without a dog.”

Brown had suffered an accident while working for the National Park Service after Hurricane Isabel. Surgery had saved him, but he was still on the mend. He hoped to be able to guide hunters during the 2006-07 season, the time for which this hunt had been scheduled, but he couldn’t.

“I’m hoping I’ll be better this year, and the doctor will at least let me shoot a 20-gauge,” Brown said. “But Scott’s a good guide, and he’ll treat you just fine. All the Cedar Island guides are family. My family has been here for four generations.”

Thanks to arrangements Brown had in advance, we were allowed to bring out own retrieving dog. Brown had Goodwin promise to make room for my retriever, Santana.

A professionally-trained retriever is an asset to any duck hunt. But until recently, retrievers had to remain at home when hunting from one of Cedar Island’s legendary “stake blinds.”

Scott Goodwin is Brown’s nephew, a nice young man of 19 with the reassuring accent common to Down East watermen.

Our ferry to the blind was an enormous workboat used for commercial fishing. The bare deck was obviously ready for crabbing or net fishing once the duck season ended.

Goodwin doesn’t begin guiding hunters until the December segment of the season when commercial fishing season declines and the bulk of the ducks arrive from the north.

The way he helped two old timers load their gear and helped make sure they wouldn’t slip in the dark was a confidence-building exercise as the wind-driven rain pelted unprotected faces looking over the forward splash screen into the blackness. Only a few channel markers blinking red and green, along with lights along the shoreline near the ferry landing, hinted humans ventured to this remote place.

Daylight was graying by the time Goodwin negotiated the sound and reached the blind. He kicked the motor up at an angle and raced the engine to make the last few yards to the blind. The boat was a 1983 Parker Southwester Sound Skiff with a 140-horsepower jet-drive outboard. The jet drive was the key to getting across the extensive shallows where a standard outboard’s propeller would have been ground to a nub.

Goodwin began tossing decoys in front of the blind, spacing them out until they covered approximately an acre — or so it appeared. He flung decoys made by G&H, Herter’s, Flambeau and a few home-made mallard decoys painted to look like scaup, which local hunters call “blackheads” or “bluebills.”

The decoy anchors were hefty, home-made affairs, cast of lead with wire loops. The sinkers were square mushroom shapes and each weighed 1 1/2 pounds. The strings were fairly short, made of tarred, braided Nylon line about 10-feet long.

“You might get a shot at a pintail,” Goodwin said. “But 99 percent of what you’re going to see will be divers. On a day like this, you might even see some sea ducks because they move more in the wind.”

Goodwin said his stake blinds hold a maximum of three hunters, but two to a blind was the ideal number. The reason dogs aren’t usually allowed in the stake blinds is they would have to climb a ladder 10-feet high.

While that’s no problem for trained dogs, it that only resolves half the problem. A dog can’t climb back down and jumping from that high into water a foot deep could injure a retriever.

“This is something one of our hunters brought down and left.” Goodwin said. “It works like a climbing tree stand. Try it out and if you like it, we’ll make some more of them. We are get more and more requests from hunters who want to bring their dogs, but we aren’t sure how the platforms will work. I do know the dog had better be steady so he’ll sit still and not scare ducks coming to the decoys.”

He affixed a platform with its floor padded with carpet to one of the poles or stakes holding up the blind platform. The dog jumped on and was right at home because he had been trained to use climbing stand platforms and floating platforms during swamp and marsh hunts. As long as he could withstand the near-freezing wind and rain without protection, he’d do just fine hunting from the platform.

The problem with adding a permanent platform is it would be washed off by waves. Even the sides of the blind are simple plywood so they can be taken down after the season and re-used the next year because the blinds are vulnerable to the elements of water and wind. A gap between the plywood and some 4-inch wood strips around the top allowed hunters to see out without outlining their faces or heads to incoming ducks.

“Stay down and look between the boards,” Goodwin said. “If they see your faces, they’ll flare because it’s getting late in the season. (The ducks) are getting a little blind shy.

“It’s hard to have patience, and I get up every 15 minutes or so to look around, and it’s sometimes a big mistake. Once I did it and looked up and a big flock of sprigtails was almost in range.”

Goodwin said a windy, overcast day with no rain created the best conditions for diver hunting. He said snow would make big rafts of bluebills take to the air, but heavy rain would make them sit tight. He also said the best wind for duck hunting comes from the north or northeast.

“I think when it’s cold enough to snow, they fly around to get warm,” he said. “If the wind blows over 30 to 35, you can’t get out on the sound to hunt.”

The problem with a southerly wind is it blows the water out of the sound. Tidal movements inside Pamlico Sound aren’t subject to lunar influence as is the ocean. Rather wind direction and velocity move the water levels up and down in different areas of the sound.

Goodwin said with a southwest wind, the water at the blinds could be so shallow his boat couldn’t reach them and the hunters would have to walk to the blinds to put out decoys and carry guns and gear.

“If you don’t know the tides and don’t know where you’re going, you can get your boat stuck or mess up your motor,” he said. “It takes a lot of days out here to learn your way around. Even then, the bottom is always shifting. All it takes is one storm to move a slough or push up a new bar.”

The guide service keeps up between eight and 10 blinds for each season, along with a couple of marsh blinds. The blinds are at Back Bay, Core Banks and the Swash.

Hunters who want to erect their own blinds can do so by visiting during the summer, washing down pilings and erecting floors and sides.

But maintaining the blinds from long distance can be difficult. A hurricane or simply a bad storm can blow blinds apart. Blinds also must be situated away from other blinds, as well as outside the boundary of the Cedar Island National Wildlife Refuge.

Some hunters have gotten into trouble setting up boat blinds, which wildlife enforcement officers found were inside the refuge.

Goodwin left us in the growing light, with the slapping of waves against 100 decoys and the howling wind through the sight gap the only sounds remaining as his outboard motor switched off as he rounded a point. We could call him with our cell phones or by radio, and he would pick us up or retrieve downed ducks we couldn’t catch.

Goodwin doesn’t typically share the blind with hunters because he’s usually attending to several parties at the same time. But he’s never more than a few minutes’ boat ride from his hunters for safety and convenience.

Within 30 minutes of daylight, our bag limits of lesser scaup had been filled. Although we could have stuck around hoping for a pintail, redhead or other duck, we opted to call Scott near noon to return and retrieve us.

The dog platform worked extremely well and Santana had weathered the storm, retrieving all of our ducks. All I had to do is go up and down the ladder to take the ducks from his mouth.

Thousands of ducks were visible in all directions on the water in the air and working to the decoys in front our blind and several other blinds.

“You guys shot pretty well,” he said. “It’s good to practice before you come down. On a day like today you get lots of chances. But on a bluebird day, the ducks may not fly as well, and you want to get your bluebill limits out of one or two flocks.

“I was on the high school trap team and shot every day; it really helped during duck season. I’m not as good as I was then.”

“Part of a successful hunt is in the shells you shoot,” Watts said. “Some hunters make the mistake of coming to the coast for a duck hunt and all that trouble, time and money to get here and shoot cheap shells or old shells. Anything worth shooting is worth shooting with a good gun shell. I toss out all the old shells from last year because I don’t want a misfire. Duck shells get wet.”

Watts prefers double-barrel shotguns, which leaves him only the option of shooting one of the polymer or “matrix” shells.

Harder shot shouldn’t be used in older double-barrel guns. The cost of these shells is not inexpensive and rumors are that for the 2007–08 season the price of matrix ammo has climbed 400 percent higher than 2006-07.

“Shooting a box of low velocity steel shot is more expensive than taking your limit with about as many tungsten shells,” Watts said. “You save more money by killing the ducks outright than by having to shoot a half dozen shells at a cripple and still having him swim away. I shoot some of the fast steel loads in a Browning automatic, and they kill ducks very well, even sea ducks. Sea ducks are some of the hardest of all ducks to kill.”

Goodwin picked us up and we motored back to shore. The sound looked much friendlier in the daylight than in the dark.

He invited us back to try our luck again that afternoon. While we could have warmed ourselves and eaten lunch, then headed back out for the 1 percent chance of shooting a pintail or redhead, we opted for heading back home and trying this unusual but entertaining style of duck hunting another day.

Be the first to comment