It’s a rare experience to hunt tundra swans and ducks during the same trip, but down east hunters can enjoy just such a thrill this month.

While a graying dawn held the promise of warmth, an arthritic sun took its sweet time creeping over the horizon last January.

Without benefit of solar radiation, the atmosphere felt like the inside of a freezer. Ice crystals sparkled in vehicle light beams like crushed stars that had been scattered across the soybean field. Frozen beanstalks crunched like cornflakes underfoot, and the frost felt like ice picks stabbing toe tips, even through the soles of thousand-gram Thinsulated boots.

Earlier that morning, Teddy Gibbs had roused us from Jennette’s Lodge at Engelhard in Hyde County. It was one of his first hunts as proprietor of Jennette’s Guide Service.

Gibbs, a 38-year-old commercial fisherman, farmer and hunting guide, began dating Tom Jennette’s daughter, 16 years ago, then married into the family.

“The first day I dated her, I began hunting for Tom,” Gibbs said. “I bought the guide service from my father-in-law, but he still runs the motel.”

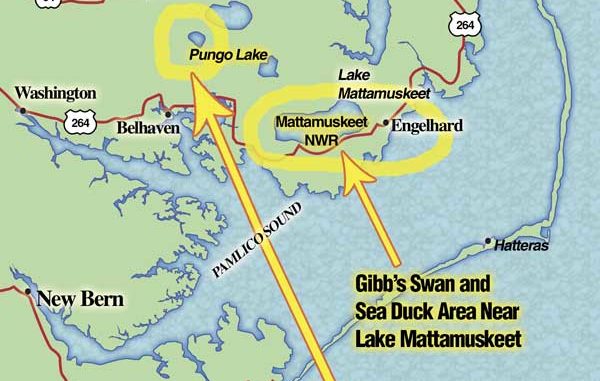

Gibbs has 10 farms he uses for hunting swans. But he prefers to combine his swan hunts with sea duck hunts at the nearby waters of Pamlico Sound.

Hunters who draw permits for swans may only shoot one of the big white waterfowl per year. Many hunters travel great distances to take a swan, so they must stay overnight. Combining a swan hunt with a sea duck makes a long journey more rewarding.

“Hunting sea ducks is the opposite of swan hunting,” Gibbs said. “A good shot will down a swan with one shotgun shell. But to kill four scoters can take an entire box of shells, 10 shots to down them and 15 shots to finish off cripples.”

Gibbs boasts a 100-percent success rate for hunters taking swans from his 4×12-foot box blinds. He hauls his blinds into crop fields using an ATV and a trailer. The blinds can accommodate three hunters and he fills them with swan decoys during the trip.

He took his decoys into the stubble, setting them in a long formation that pointed upwind of the blind. He left an open landing zone approximately 25 yards from the blind, and no decoy was set more than 50 yards away.

“You want the birds to decoy right over the blind or right in front of it,” he said. “They’re fairly predicable at landing into the wind. But if there’s no wind, they might pitch anywhere, even outside the decoys.”

This morning the wind was raw on the cheeks and frost was on everyone’s toes. As daylight grew, swans began flying from a roosting site at nearby Lake Mattamuskeet.

As their whistling and peeping calls filled the air, the swans began to come to the decoys. As a big adult swan came into the decoys with his body rotating down on pivots of wide-cupped wings and his black feet stretched toward the ground, my wife Carol fired twice and a 3-inch, 12-gauge load of No. 2 Hevi-shot took the swan cleanly.

“That’s a nice bird,” Gibbs said. “He weighs 16 pound or more; some can go over 20 pounds.”

Swans were moving in all directions, and it was so cold, batteries were freezing to uselessness inside cameras. Pocketing a battery pack to warm it, I was pulling on a white suit to sit in the decoys and try my luck with a bow and arrow when a pair of adult swans landed just outside the decoys.

I put together my take-down bow while half-dressed and nocked an arrow. Launching it, the shot seemed perfect until the arrow began drifting in the steady wind. It struck the ground to the side of the bird.

This swan had enough warning, with the archer balancing on the seat of the blind, silhouetted by a low-hanging sun, and lifted off. But another bird, identified as a juvenile from gray plumage, landed in the decoys. Other swans called overhead as I finished preparations and stepped outside the blind.

The swan alternated sitting on the ground and walking closer to the decoys, seeking warmth and companionship. Fortunately, he kept moving closer to the center of the decoys while I crawled toward him while hiding behind decoys to keep from being spotted. He tucked his head across his back while resting his body on the ground. His eyes were hidden as I rushed to within 20 yards and made a perfect shot arrow strike.

“That’s my first archery swan,” Gibbs said. “I’m happy to say my clients are still 100 percent on swans.”

“There were swans circling at all levels above you,” Carol said. “I knew you couldn’t look up, but you should have seen them. There were four or five flocks with dozens of swans. The clicking sounds of their wing feathers vibrating and their calls are the most exciting thing I’ve ever heard.”

It took longer to put out and pick up the 30 full-body and 18 shell decoys than it did to take two swans. A good night’s sleep and an afternoon’s rest paid off the next morning.

Gibbs left the dock in his 35-foot commercial crab pot/scallop dredge/trawling boat. In winter, he converts the multiple-use boat into a sea duck tender. He towed an 18-foot Glassmaster boat stripped bare inside. Plywood panels, painted battleship gray, had been added to the sides, leaving an opening across the top, extending bow to stern, for shooting.

“I can put three hunters at either a sea duck or swan blind,” he said. “Out of a group of 30 hunters, six or eight might not have a swan permit. But they can still watch the swan hunt then participate in a sea duck hunt.”

Gibbs headed toward Middle Ground, 6 miles offshore in Pamlico Sound. He watched the radar screen to navigate the featureless sound, pointing out eerie green masses.

“There’s some sea ducks,” he said. “They look different from sea gulls because they’re more scattered out.”

Gibbs anchored the boat blind in the area where he saw sea ducks on the radar. The boat bucked like a bronco in the wind chop as we climbed inside. He handed us our gear and guns and left us, linked to each other only by hand-held radios.

“There might be some old squaws, but they only give a passing shot because they don’t decoy,” he said. “You want to watch out for buffleheads and bluebills, and there may even be a canvasback.”

Gibbs had advised bringing No. 2 steel shot. He also said a 10-gauge was better than a 12-gauge.

“The heavier the shot charge you can shoot, the less likely a cripple will get away,” he said.

Sea ducks began swarming at dawn and the shooting was as tough as it gets. From the rocking boat, shots went high, low and mostly behind. It was easy to see the shot patterns on the water because the sea ducks streaked by only a couple of feet above the decoys.

Gibbs had placed the decoys in trotline-like strings. They consisted of magnum scaup decoys painted to resemble scoters — mostly black except for white and orange on the drakes’ bills. He set out nine strands of fake birds for a total of 60 decoys.

As ducks were downed, Gibbs responded to radio calls by moving to the ducks and retrieving them with a long handle fish-landing net. He waited in position approximately 500 yards downwind where he could watch the action. Occasionally he called just to see if all was well.

After a couple hours shooting, the hunt ended. Ice had formed on the sides of the boat blind but had begun melting in the sunlight. The plywood only offered so much protection against a wind-chill factor we didn’t want to calculate, so the warmth of the cabin was welcome as Gibbs turned the boat toward home.

Willie Allen operates Outback Outfitters in Washington and Hyde Counties. He also takes clients on combination hunts.

“We get lots of swan hunters,” he said. “We cater to bow hunters almost as much as we cater to gun hunters. A bow hunt can last all day, with hunters shooting 30 arrows at flying swans, picking them up, then shooting them again.”

Allen said he had some archery manufacturers pro staff members show up for a swan hunt. Unlike most wing-shooters who use stick bows, they were using compound bows.

“The first two swans decoyed at 30 or 40 yards,” he said. “Those guys shot one arrow apiece and killed their swans. It was amazing.”

Allen said it demonstrates the importance of practice shooting arrows at aerial targets. He said he’s had some WRC enforcement officers who practiced a lot take swans with few arrows. He also hosts some members of the North Carolina Bowhunters Association each year.

“Some years, the NCBA members get their swans with a few arrows and some years the birds don’t decoy as well and some of them won’t even kill a bird,” he said. “It all depends on how much you’ve practiced and how the birds are flying. For a bow hunt, you want to come early in the season before swans get educated.”

Allen’s gun hunters get inside his plywood box blind, after he tows it to fields he has planted with wheat. A couple of acres of green wheat, contrasting with the brown of harvested grain fields, is all it takes to convince swans to put down their landing gear. He also coaxes the birds closer by using his voice to mimic their calls.

“Everyone likes to imitate swans,” he said. “It’s part of the fun, and it works.”

Ralph Jensen, a custom call-maker from Wilmington, took his first swan during 2006 while hunting with Allen.

“It was the most beautiful hunt I’ve ever been on,” Jensen said. “Just seeing and watching the swans work the decoys is astounding.

“I’m going to try to make some custom swan calls. It’s such a haunting sound, and there are so many different calls. Once you hear them, you never forget the music made by flocks of swans.”

If bear or deer seasons remain open, Allen also accommodates hunters with big-game hunts. But he also provides sea duck hunts and impoundment hunts for puddle ducks.

“Waterfowl hunters usually prefer to stick with waterfowl,” he said. “I have a lodge where hunters can stay, and it keeps everyone together.”

There are also some bed and breakfast inns nearby to take the overflow and to accommodate hunters whose wives may want to tag along and watch a swan hunt, then go view the architecture and other sites in the nearby historic communities.

“A swan hunt is a big event all by itself,” Allen said. “I’ve had girl scout troops along to observe a swan hunt and taken other people who just want to watch. It’s a great hunt for kids because there’s lots of action and the birds are relatively easy to hit. You just put the gun a foot ahead of his bill, and if he’s in range, he falls.”

Part of swan hunting with Allen is the setting and retrieval of the decoys. Allen uses so many decoys, shotgun hunters can’t even enter the blind until they’ve been removed. Archery hunters put plywood platforms in the bottoms of ditches and sit on stools or buckets while wearing white suits as Allen spots swans for them and calls from inside the blind.

He uses snow goose shell decoys, rag decoys and windsock decoys that can total more than 100. During cold mornings, hunters join in to set up the decoys. While it’s part of the fun, it also helps everyone stay warm.

“Swans sometimes sit on Pungo Lake until way after the sun comes up if the ground is frozen,” Allen said. “But sooner or later, they have to feed, so they’re going to fly off their roost.”

The only thing that can go awry is when swans start landing at nearby fields. Swans are increasingly wary and can tell the difference between decoys and the real thing.

“There’s no way you can make as much movement and as much noise as a real flock of swans,” Allen said. “But with wind making the decoys move and everyone making swan calls at them, you might turn a few flocks over the blind any time of the day.”

Be the first to comment