Fall might be time for raking leaves, but at Santee Cooper, it’s all about picking bream out of the brush.

Floating on the featureless surface of Lake Moultrie reminded me of my honeymoon.

My bride and I spent several days fishing in Baja, Mexico. We started the trip offshore in typical sportfishing boats out of Cabo San Lucas, boats equipped with the latest rods, reels, navigation and fish-finding equipment.

The latter half of our trip was quite a contrast to the way it started.

Fishing on the Sea of Cortez side of the Baja peninsula from another resort, we boarded a spartanly-equipped panga, a typical V-hull fiberglass boat with a tiller-handled outboard. The most sophisticated piece of equipment on the boat were the shoe laces on my deck shoes —and they were worn out. There was no depthfinder or compass. Yet, we enjoyed a fishing trip of a lifetime.

My wife and I watched with some reservation as our Mexican captain flashed glances from horizon to horizon across a dead calm sea. Even the shoreline a couple of miles in the distance was a blended streak of grey since the sun hadn’t even cracked the sky yet. Being American tourists, we sort of felt like we were on a piscatorial snipe hunt.

It turned out, however, that our captain’s GPS data card was in his head. He did some more maneuvering and then muttered the words “Free spool” in broken English.

While my wife and I pulled line off of the ancient and well-used Penn rod-and-reel combos, our guide scooped up some sardines and pitched them overboard. He then put a sardine on each of our leaderless hooks, picked up our piles of monofilament line and gave each their best Lone Ranger rope toss.

Within seconds, the Sea of Cortez erupted in a fury of breaking yellowfin tuna, and both my wife and I, shell- shocked, were hooked up immediately. How he knew to stop right there without a depthfinder, GPS or compass is beyond me, but I am guessing it had a lot to do with those stares at the dim shoreline. Our captain was triangulating to find our fishing hole.

That is exactly what Capt. June English was doing on Lake Moultrie. While three of us sat as motionless as an unbothered bobber, English scanned the Berkeley Country shoreline and glanced at his depthfinder while he eased us into position with the 9-horsepower outboard kicker.

Just like the Mexican captain, English swapped looks from side to side. Once the depthfinder showed a blip upwards off of the bottom, he told us to drop our lines overboard. As fast as the tunas hit in Mexico, bream were slamming our crickets. Two hours and two or three brushpiles later, we had a 3-person limit of bream — and some crappie and blue catfish to boot.

What a way to spend a fall day in the Lowcountry! You can do the same even if you do not maintain your own brushpiles.

Brushy beginnings

Capt. Steve English of Cross — son of Capt. June English — asked, “Did my dad ever tell you the story of how he discovered fishing brushpiles for bream?

“My dad always maintained brushpiles, but he did it with crappie fishing in mind,” said the younger English, who now carries a lot of his dad’s parties as Capt. June winds down his guiding career. “Of course, the main bait for crappie is minnows, which is not a real attractive bait for bream. He would occasionally catch a really nice bream on a minnow, but he would not give it much of a second thought.

“My dad had a father-and-son group from Atlanta that would come down fishing with him a lot. One day the father said, ‘I am going to bring along some crickets just to see what happens.’ The guy brought along about a tube-and-a-half of crickets, which is 150 or so baits. My dad thought he was crazy. You have to keep in mind that until then, brush meant crappies to him.

“They had used all of the crickets in 30 minutes, and my dad has been fishing brush for bream ever since then,” English said.

Biological piles

It doesn’t matter whether you are fishing a tiny farm pond, fast-flowing mountain river, meandering saltwater creek or the Gulf stream, any angler worth his best fishing rod knows that fish like structure.

Bream, spot, largemouth bass, catfish, redfish or dolphin — you name the species, and more than likely, most of them are caught in affiliation with some kind of structure.

Structure can take many shapes and forms. It may be a toppled treetop or a sunken subway car, a lone rock on a skillet-flat ocean bottom, a point riddled with oysters or a quick dropoff. Fish also orient themselves to currents and temperature breaks. These situations are not objects, but they do change the water column as much as something that is visible and permanent.

But what it is about brushpiles that make them so attractive to bream?

“Many fishermen believe that brushpiles will physically increase a panfish population,” said Scott Lamprecht, a fisheries biologist for the S.C. Department of Natural Resources. “It is true that brushpiles will shelter small, young-of-the-year fish, which may add a few more fish to the overall population. The concept is the same as building brushpiles on land for rabbits or quail.

“Brushpiles add habitat diversity, which is very limited in older reservoirs such as Santee Cooper.

“When reservoirs are created,” Lamprecht said, “a tremendous amount of vegetation and woody material is flooded. This supports a tremendous food web, but as this material decays, it becomes less productive and, in many cases, simply disappears.

“Brushpiles recreate those productive areas, but on a much smaller scale, and (they) provide structure that is lacking.”

Given a bream’s annual cycle, brushpiles function as a rest area on the turnpike of life.

“The brushpile fishery for bream seems to be primarily a spring and fall phenomenon,” Lamprecht said. “You can catch fish off of them just about any time, but really the best action is during these two times of the year.

“Bream can spawn all summer, which is a shallow-water activity. They use the brushpiles as staging points as they move towards and away from the shallows. During the summer, some fish may retreat to brushpiles closest to the shallows, but they really stack up on them when they’re not affiliated with spawning spots.”

Building brushpiles

It seems logic would dictate that using public waters as a dumping ground would be illegal. The truth is, you can toss a bunch of debris into a lake as long as you follow a few rules.

“It is legal to build brushpiles in the Santee Cooper lakes as long as they do not pose a navigation hazard to boaters,” Lamprecht said. “Further, you must use inert objects to weight the brush. Using an oily engine block is definitely out of the question. Don’t put anything in the lake that would pollute the water. A good option is something made of concrete, such as a few cinder blocks.”

Because bream key towards brushpiles as they are m moving to and from spawning areas, it is best to position piles to take advantage of this movement.

“You want to have brushpiles in all depths,” Steve English said. “Piles that start in about 10 to 15 feet of water and run out to around 35 or 40 feet are good.

“As the water begins to cool in the fall, bream will start leaving the shallows and head towards deeper water. For example, early in September I might be having the best luck on the shallowest brushpiles. But as the month progresses, I will be fishing deeper brushpiles as the fish move. This will continue all the way until about the end of November or early December, when the fish seem to stop biting.

“The last fish I catch for the year will be in water 35 to 40 feet deep. The whole pattern will reverse itself the following spring.”

English positions his brushpiles in areas with a depth change. A good spot to him is where a hump occurs or along a slope. It has been his experience that situating a brushpile on a large flat seems to be less productive.

“For some reason, bream prefer fresh brush more than crappies,” English said. “If you build a brushpile, it may remain good for crappies for three or four years, but a good bream brushpile will need new material on it every year for it to remain productive.”

Lamprecht said that a variety of materials make good bream brushpiles.

“Fresh, wet timber is easier to sink than material that has dried out. Good material for brushpiles is stuff that is evergreen and provides a lot of surface area.

“Wax myrtle bushes are really good, for instance, because they have lots of limbs and leaves, and they grow back from the stump, offering additional brush in the future.

“Other good stuff is live oak and willow limbs and cedar trees,” Lamprecht said. “You can even bundle together bamboo poles.”

It was thought that some artificial material, such as PVC pipe, would be a good alternative to natural material. Lamprecht explained that artificial materials may last longer, but they don’t provide the surface area or natural intricacies as the real stuff.

English has taken over his dad’s piles and maintains about 100 to 125 in both Santee Cooper lakes.

“Maintaining brushpiles is a lot of work,” he said. “I have to really diversify what I maintain to take advantage of fish movements, but also which ones may be available to fish given the weather and wind.

“If you are a weekend fisherman, six to eight well-placed and maintained brushpiles will more than meet your needs,” English said. “Keep in mind that it could take as long as two years before you know if a brushpile is going to be any good, so don’t give up on one too soon.”

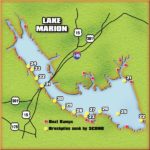

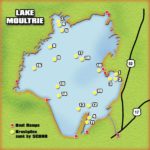

If you are not able to build and maintain brushpiles — or simply don’t have the time — the SCDNR maintains an active brushpile program in every major reservoir in the state. For example, there are 32 brushpile sites in the Santee Cooper lakes.

Reaping what you sow

If you have built your brushpiles or decided to take a trip to Santee Cooper to fish some of the public brushpiles, it is time for the easiest and most-fun parts.

“Fishing for bream on brushpiles is pretty simple,” English said. “First, it is wise to use a GPS and depthfinder to aid in relocating the brushpile. Once there, tackle is very basic.

“I prefer to use a 7-foot Shakespeare 2-piece ultralight rod spooled with 4- to 6-pound-test monofilament line. Whether to use a spinning or baitcasting reel is a matter of personal preference, but I opt for the latter.

“My dad uses a 9-foot rod. The advantage to using a longer rod is, once you have determined what depth the fish are located, you can land the fish just by lifting up the rod and not reeling any line most of the time. After you rebait, all you have to do is drop the cricket back down.”

The rest of English’s tackle is a No. 4 long-shank hook and a split-shot or two positioned about four to six inches above the hook. He prefers a long-shank hook, because bream frequently swallow the whole bait, and unhooking the fish is easier with a hook that has a long shank — you can get your fingers around it.

“Bream are notorious bait stealers,” said English, who believes that crickets are the top bream baits. “I can really feel what is happening down there if my weight is close to the bait.”

Since most fishing is in water greater than 10 feet deep, you don’t need any sort of float or bobber.

“I have never seen where the weather, moon or time of day has drastically affected the fishing when bream are on the brush,” English said. “Crappie can be finicky, but bream pretty much slam everything dropped down there in the fall.

“If you don’t have a bite in 15 seconds or so, then you either aren’t over the brush or the fish are at a different depth. Likewise, bream seem to associate by size. So, if you are catching a bunch of small fish, I would suggest moving to another brushpile to attempt to locate some larger fish.”

Whether you’ve been married 50 years, just gotten married, or aren’t married at all, fishing for brushpile bream will make a trip of lifetime. The best part is, you don’t have to travel as far as Mexico.

Be the first to comment