The Savannah River swamp is unique among places where South Carolina hunters can chase a tom turkey. Here’s how and why.

The Savannah River swamp is a formidable arena for wild game, including centuries-old cypress trees, oxbow swamps and endless pockets of primo habitat.

In days past, when turkey populations were under stress, it was places like the Savannah River swamp and the Francis Marion National Forest that remained strongholds because the old toms were too tough to root out. Today’s Savannah River turkeys are still flourishing, and they are still just as tough to tag.

Large tracts of land along the Savannah River are just one piece of the habitat equation that benefits turkey, deer, hogs and even songbirds, amphibians and more. If you’re looking for a wild setting, the back channels of the swamp will suffice, and the turkeys that are calling from one cypress ridge away will know escape routes so well that often a guide with knowledge of the terrain is needed for best success.

Counties that border the Savannah River swamp in the Lowcountry are: Allendale, Hampton and Jasper. While the hardwood corridor that runs alongside the river’s floodplain is impressive, at times giving hunters a sense of awe, the associated creeks that flow into the river, oak flats and adjacent pine woods all form a mosaic that gives turkeys lots of ground to travel.

“Our guided hunts are all booked up for the first two weeks of turkey season, and we have a waiting list for any cancellations,” said Jeff Hunt, a guide at Cypress Creek Hunting Lodge in Estill. “Depending on the weather, these turkeys may already be heading out of their first peak of gobbling activity.”

A long, cold winter and late spring will hold back the usual early peak of gobbling, while warmer weather gets them fired up much sooner.

With 7,500 acres that includes a portion of the river swamp, Cypress Creek Hunting Lodge covers a large area.

“We will hunt all morning if necessary, from dawn until 11 a.m., before breaking for lunch,” Hunt said. “The birds are more vocal in the morning, so that’s when we have the most luck, but we kill turkeys after lunch, too.

“First thing at dawn I like to do is to use my slate call very softly to check for nearby turkeys, because most of the time they are closer than you think,” said Hunt, who carries at least five different strikers. “Each day you never know which sound they will respond to, so I vary that pegs I use. You can make loud calls with a slate, but I value their ability to make almost any sound of the turkey softly.”

“Afternoon hunts is where our scouting pays off, because when we harvest these toms, they are often in patterns that keep them on oak flats or areas where a prescribed fire was conducted,” said Hunt.

Bill Mixon of Furman guided hunts for years at Palmetto Bluff on the coast before settling back into the Savannah River swamp area to guide; it’s an area that he has called home all his life. Mixon has earned the moniker “Ridge-Runner” for all the cypress swamp bluffs and cuts he has used to circle around toms. His championship-caliber calling has only been heard by the folks lucky enough to hunt with him — and the longbeards fooled and drawn into shotgun range.

“I start all my turkey hunts with an owl call,” said Mixon, who uses his own voice to make hoots that pierce the quiet, dark swamp. When the gobblers hear that sound, more often then not they will shock-gobble, and Mixon can dial in on their exact location. Once a turkey has sounded off, Mixon will quickly choose a set-up location and start calling.

“Usually, I don’t have to call to them too loud at first, especially if I’ve chosen a good set up in an area that they already want to be in,” he said. “Choosing how close to move towards a roosted tom depends on whether the forest is open or grown up. I can make every sound of the hen turkey, but no one can duplicate a hen walking into a strutting tom, and that’s where turkey hunting gets interesting.”

Walking down a road, we heard a tom gobble in first light back on a large oak flat. Mixon set up across the open flat, still out of sight of the tom at the far end, but no matter what he did, he couldn’t lure the bird across the open space.

“I’m gonna make a note of what that bird likes to do, and I’ll be back to crack that nut later,” he said.

From that bird, Mixon headed to one of his honey holes. Walking into the swamp from a live-oak ridge, our rubber boots began sucking into the moist earth. Mixon chose two trees and began to call, and immediately, multiple turkeys began gobbling. After just 10 minutes, three birds marched in close, strutting.

“Get ready,” said Mixon in a whisper. With my gun up and armed with confidence, I waited for my chance. The birds stopped and began looking towards us, but I had a dwarf palmetto between them and myself.

“That’s it, take your shot,” Mixon whispered, this time with more purpose. I stretched my neck to see around the palmetto and took my best shot — and have regretted it ever since.

Dwarf palmettos are abundant, but while deer hunters in an elevated stand are not inconvenienced, a turkey hunter sitting on the ground can have an obstructed view.

Disappointments make those times when you find a grassy, open and sunny area in the hardwoods all the more pleasurable. Knowing that the toms like to strut in that type area, a hunter can get there first, then set up and wait. Woodsmanship cannot be underestimated when hunting a swamp gobbler, and Mixon moves like a ghost between spots.

“Often the key to killing a swamp turkey is to get to certain set-up zones without being detected, and then let the hunt come to you,” he said.

Jim Boone, owner of Red Bluff Lodge in Allendale, has 6,000 acres of prime turkey land, including a tract in the river swamp to which gobblers flock.

“Turkeys are one of the most beautiful creatures we have in the woods,” Boone said. “There is no more awesome sight or sound than that of a gobbler strutting, drumming and gobbling. It is an honor to witness them in action.”

One hunt started with three longbeards gobbling in a hardwood bottom, not very far from where they were predicted to be. We called to those fellas, hopeful they would think that some ladies were just up the rise, but they would not budge.

The calling did eventually attract three hens that came right in before realizing no gobblers were to be found. They walked down into the creek bottom, and the three toms began gobbling like it was Fat Tuesday, giving witness to the meaning of “henned up.” Early in the season, with gobblers busily mating, a live hen beats any hunting tactic or strategy.

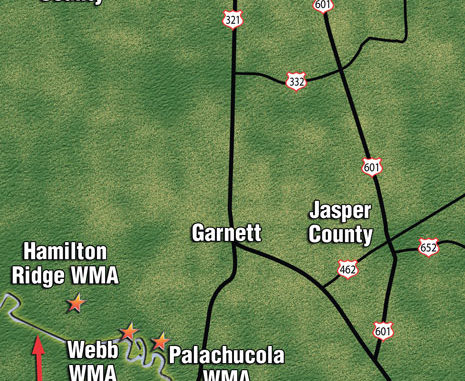

Jay Cantrell, a wildlife biologist with the S.C. Department of Natural Resources, is in charge of the 25,000 acres of WMA land along the Savannah River comprised of the Webb Center WMA, Palachucola WMA and Hamilton Ridge WMA. Public hunting is available during April.

He said that while these WMAs may be a bit crowded on Opening Day, usually by the end of the season it’s not hard to find a secluded spot to sit and call for a longbeard looking for some late-season companionship. Without a guide, it is possible to get turned around or slightly lost in the swamp, but once you reach the river, you have to stop. To get out, you can generally put the river to your back and walk until you find a woods road on higher ground.

The Savannah River can work for hunters sometimes, too, as when it is in flood stage and most of the hardwood corridor along the river is completely flooded. That’s acres and acres of swampy habitat that the turkeys can no longer operate in — and that’s an advantage for the hunter.

One time during a large flood, I found a bird roosted out over the water, likely in its usual roosting area. It was all too easy to set up on the high bank, call to the 22-pound tom and provide exact coordinates for him visit. The result? Boom!

I thought I might have heard another bird fly over, so I sat tight for 20 minutes, still making calls. When I stood up, I looked behind me and another gobbler had silently walked up behind me.

While that second gobbler got away clean, the lesson for hunters in the Savannah River swamp is that turkeys are social, and seldom in this type of terrain are they completely alone. Best of all, Savannah River swamp turkeys will likely make those who seek them into better turkey hunters, which will translate to more hunting success wherever you set up and call to the spring monarch.

Be the first to comment