Patience certainly can be a virtue when pursuing late spring-season wild turkeys. Using decoys also can fire up reluctant longbeards.

One of the tenets of successful trophy deer hunting also holds true for chasing spring wild turkeys — go where the gobblers are.

That’s why trophy whitetail hunters don’t circle North Carolina as a favorite destination but instead prefer Illinois, Iowa, Texas and midwestern Canadian provinces.

But with wild turkeys overspreading most of North Carolina, a successful hunt would seem to be only a matter of finding some nearby turkey territory, private or public, arriving 30 minutes before daylight, listening for gobblers, moving within a couple hundred yards of a noisy bird, finding a good ambush spot and yelping like a hen turkey.

A few minutes later, bang, turkey down, right?

It ain’t that simple, especially near the end of N.C.’s April-May season, as any longbeard chaser can tell you.

One key factor — patience — should help a hunter fill his spring-gobbler tag, especially during the season’s final two weeks.

A few years ago, after marrying a lady whose family members are long-time residents of turkey-rich Caswell County, I had a chance to hunt some virgin longbeard territory. None of the relatives living near my wife’s aunt were turkey hunters, although they were living within a load of No. 6 shot of outstanding habitat — and plenty of birds. They saw wild turkeys nearly every day and were so accustomed to the sight of gobblers and hens crossing fields and roads near their homes, turkey season was mostly a time to plant “bacca,” sweet taters or corn.

One May morning I pulled into the yard at the home of my wife’s aunt well before daylight — after asking permission to hunt her 150 acres several weeks earlier. I had a walk of approximately one-quarter mile down a muddy, rutted lane leading to several grown-over corn fields behind her house. I’d already scouted and seen big turkey tracks, dusting areas and gobbler feathers at these fields’ edges.

However, I’d left my job only four hours earlier (at the time I worked for a mid-size daily newspaper that closed out the city edition at 1:15 a.m.). As you can imagine, I was pretty much spent. However, the excitement of trying a new place had pumped my system full of adrenaline that morning.

In addition to wearing the usual camouflage clothing, I carried two collapsible decoy turkeys I’d purchased at a well-known “big-box” store, a camouflage dove stool, and a swath of folded-up camou netting I’d stuck inside the dove stool’s cloth pocket, sewn underneath its seat.

I’d read somewhere that older gobblers are territorial — they protect their turf from the intrusions of other male turkeys, especially “jakes,” and would come running, itching for a fight if they thought a whippersnapper was trying to make time with one of their girl friends.

So one of the decoy turkeys was a jake and one was a hen.

“They’s a big ol’ gobbler that hangs around with a bunch o’ hens in the woods where that old house is in the woods at the corner of that big field where we got a high (deer) stand at the corner,” my wife’s cousin’s husband had said to me during a March dinner.

At that time, Billy didn’t hunt gobblers, but today he’s a turkey nut, like me.

“But I’ve seen those turkeys more often than not in the little field before you get to the old house,” he said.

I knew the place. Before I reached the slowly crumbling log house, a four-wheeler path skirted the edge of a square 2-acre field.

I found a spot at this small field’s western edge, 10 feet inside a pastel-green woodscape and between three trees with enough space between them to wedge my stool inside their rough triangle. I used some old wooden clothespins to clip my camou net to small branches surrounding my chosen ambush. Then I placed the jake and hen decoys about 25 steps into the field from the makeshift “blind.”

Any turkey gobbler coming into the field would see the two false turkeys, perched on sticks I’d sharpened at each end. These hollow foam decoys are so light weight they’ll turn at the slightest breeze, which apparently tricks real turkeys into thinking they’re alive.

More importantly, I was hidden well and couldn’t be seen.

Carrying a Remington 870 12-gauge 32-inch barrel full-choke “goose” gun (it once bagged a gobbler at 50 yards), I was ready. After a few minutes to let things settle, I used a slate call to produce six hen yelps. To my surprise, a gobbler roared back, less than 100 yards away in a pine thicket.

My heart thumped wildly.

But he wouldn’t come closer, even though he gobbled each time I purred and yelped with the slate and a box call. Finally he moved too far away to hear my calls — I thought.

“Oh, well,” I said, “he must have some hens with him.”

It’s basic when hunting to be alert. Stories are legion about hunters who weren’t paying attention and paid the price by having a big buck or boss gobbler walk past them undetected.

But in turkey hunting, it doesn’t always work that way.

The morning shadows shrank as the sun beamed brightly. Bees and assorted insects hummed in the golden, pollen-filled air. Geese honked somewhere behind me. A dog barked.

With my back to one of the trees and warmed by the ascending sun, I nodded, then dozed.

Suddenly I awoke with a jerk. A foreign sound had startled me out of a deep slumber.

I looked at my wristwatch; it was 11:30 a.m., which meant I’d been asleep for four hours that seemed like four minutes. The major benefit was I hadn’t been rambling and let myself be seen. And apparently I don’t snore while sitting upright.

“Yawk, yawk, yawk,” I heard several turkeys to my left along the tree line.

A handful of hens, about 50 yards from me, were fussing at something they didn’t like. Their yelps and squawks sounded like scolding.

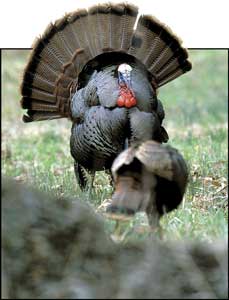

Then a big, black-feathered gobbler with a blood-red head burst through the gals into the edge of the field. He puffed his tail feathers and glistened bronze, brown and white in the sunlight.

Then he saw the decoys and made for the faux jake on a dead run, the harem behind him screeching, “Don’t go there!”

He ran to the jake decoy and bumped the foam facsimile with his chest, then “blew up,” his wing tips dragging on the ground. He spun, making a lethal mistake when he faced away from my 870 pumpgun.

He weighed 20 pounds and sported an 11-inch beard with 1 1/8-inch spurs.

Patience.

The old boss bird apparently had remembered the calling session with me hours earlier and had fixed in his internal radar system the exact location of that lone “hen” and forced his reluctant harem back to the fateful spot.

And I was waiting for him because I’d been patiently slumbering.

I had a similar experience with patience — but sleepiness played no role — last spring in Orange County when Michael Kirk, son of well-known field-trail dog trainer and handler Bobby Kirk, invited me to accompany him during a hunt.

Michael was recovering from a truck wreck in which he’d been thrown from his vehicle after a Richard Petty-esque roll in a narrow “S” curve one night between Chapel Hill and Eli Whitney. Lucky to survive (the truck settled on his legs), he had to wear a full body cast for months, which quashed his turkey hunting hopes. His doctors had advised against shouldering or firing a shotgun.

But he was itching to get in the woods and avoid the worried looks of his grandma and aunt, who took care of him while he healed.

I suspected the place he’d chosen might harbor turkeys, some of them huge gobblers.

But after we parked in the dark and first light turned the world from black to gray, Michael owl-hooted and I crow-called. Even the owls and crows ignored us.

“Let’s go over to a field I know where I saw turkeys last year,” he said.

As we walked, I noticed a narrow ribbon of green, stretching toward the east. Hardwoods encircled the weed-spackled field I later learned once was a prop-plane landing strip. I thought that field edge might be a logical set-up to waylay a gobbler searching for amorous hens. But Michael’s hot field was across the next ravine and on the other side of a ridge.

We continued to walk, and I said nothing.

I placed the decoys in the field in front of us, got settled against a tree on the ridge, with Kirk about 30 yards to my left, hidden against a decent-size maple growing in the windbreak.

We began to make hen yelps, and, sure enough, a gobbler roared in the ravine east of the first long field we’d by-passed.

“Dang, he’s behind us,” I said, whispering to Kirk and pointing my finger.

About 5 minutes later, I craned my neck to look as the tom answered our calls from 400 yards away. I raised my field glasses and saw what appeared to be a white softball moving along the edge of that field. The gobbler’s head seemed to be at my chest level above the ground; his body seemed as big as an ostrich’s.

He walked directly west, in the road we’d just traveled in our trucks, gobbling at our calls until he was perhaps 350 yards west of us.

“What do you think?” I whispered at Kirk.

Moving was out of the question because the gobbler might see us.

Belying his youth, Kirk said, “Let’s just sit here a while and see what happens.”

Always listen to your caddie when you’re playing a new layout.

We listened for perhaps 40 more minutes, giving hen yelps each 10 minutes or so. Then we heard a faint reply — gobble, gobble, gobble.

He’d turned but would the tom come back?

“He’s probably about 250 yards from us and can’t see us, so let’s switch trees,” I said.

We kept low, frog-walking as we changed positions to put my gun nearer the bird. We settled back and began to yelp. When the big gobbler answered, we knew he was advancing toward us.

When he was within 100 yards, we stopped calling. If he kept walking toward us, he’d eventually see the decoys.

A lone pine about 10-feet tall was in the field about 100 feet from me. From my low angle, I barely couldn’t see through the pine’s lower limbs. Then the bird’s tail feathers, fanned out on the other side of the pine’s branches, caught my eye.

He was in the classic strutting pose, wanting the “hen” to see him and come say hello. When she didn’t, he slowly moved around the pine — and spied “Jake Who’s Not A Drake.”

Neck stretched out, his wattle blood red, the turkey started running, his feather-covered chest shaking from side to side.

I rolled him with one shot when he passed in front of me, headed for the two decoys. This gobbler weighed 22 pounds and had a 10 3/4-inch beard and

1 1/4-inch spurs.

“Glad we waited,” Michael said. “But I didn’t think you’d ever pull the trigger.”

When we thought about this incident later, it was obvious what had happened. The gobbler probably didn’t make a beeline for us because he wasn’t going to go down into the ravine and walk up the next ridge. Turkeys like to be above whatever holds their interest. If danger — a fox, bobcat or coyote — pops out, they can take flight more easily from a higher position than from the bottom of a steep hill.

So this old bird had taken a rough semi-circular route at the same elevation and a little higher than our false flock (and us). When his girlfriend didn’t appear, he took his time advancing toward her. He strutted, while hoping to meet her coming to him. When she didn’t appear, and the old tom spied Johnny the Fake Jake, he lost his cool — and his head.

And ain’t that a familiar story?

So if you’ve got a little time and aren’t rushed during your spring hunt this year, take it easy, maybe even enjoy a nap if you’ve had a gobbler show interest, then wander away.

But be sure to place at least two decoys within gunshot range of your hiding place. If you don’t and fall asleep in your blind, you may wake up to see a turkey poking its head through the camou netting, wondering what kind of hen snores like that?

Be the first to comment