I hate to crawl on my soap box, but what I saw recently on television stuck in my craw too much to overlook. I’m referring to some of the fishing shows and how much stress alleged “professional” anglers put on fish by incorrectly handling them.

I don’t claim to be perfect, but I work hard to not mishandle fish I plan to release. We also try not to use photographs in the magazine that suggest improper handling of fish to be released.

Catch-and-release fishing isn’t just about removing a hook and returning a fish to water. It’s also about handling the fish in a way that best enhances its probability of surviving. Sometimes that means leaving a hook in a fish rather than subjecting it to the physical damage and trauma of removing the hook.

Don’t get me wrong. Often I don’t plan to release fish I catch. Still, when releasing fish is the goal, there are helpful and harmful techniques.

The goal is to always work to best ensure a fish’s odds for survival if it’s going to be released. And that means handling — or sometimes not handling — a fish. Sometimes the size and rambunctiousness of a fish dictates what you can do as far as live release goes.

It’s easy to get upset with anglers who brag about how many fish they release only to discover their idea of release is ripping the hooks out as quickly as possible and throwing the fish into the water. Don’t take my criticism incorrectly — I’m really happy people can enjoy fishing without having to keep every fish they catch. I just believe they need to understand and practice the best way to handle fish and remove or clip off a hook to give them a chance to survive.

I also think it’s far more wasteful to release a legal fish that was fought to a point beyond revival or has been handled in a way that severely reduces its chances of survival than it is to take that fish home and eat it.

Recently I watched a TV show where king mackerel fishermen fought 40- and 50-pound class fish to the point of exhaustion so the anglers could grab the kings by the tails. As the fish struggled, anglers lifted them out of the water, dragged them across the gunwales and removed the hooks.

Fish are surprisingly resilient, and these kings may have survived, but they had three strikes against them before being shoved into the water. At least they were dropped head first so momentum could start a flow of water across their gills, giving them a chance to revive.

Strike 1 was fish of this size were fought to the point of exhaustion so the anglers could more easily handle them.

Strike 2 was the fish flopped and banged against the boat and gunwale as they were lifted from the water, which likely damaged their internal organs that may have shifted out of place (a king mackerel’s internals are held in place by thin membranes).

Strike 3 included dragging the kings across hard surfaces in the boat that scraped off their slime and scales and added more bruising. The slime and scales protect fish from infections, diseases, water-borne bacteria and fungus. If slime and scales are removed, a fish has much lower resistance.

When fun fishing for king mackerel, I don’t keep larger fish unless I judge them to be beyond the point of survival. Biologists have said larger kings are primarily females and are the heart of the breeding stock.

To aid in releases without handling, I use multi-strand wire instead of the single strand I use during tournaments. Multi-strand wire isn’t as tooth-proof as single-strand wire and easily can be cut by a pair of fishing scissors. It sometimes is bitten through by aggressive or large fish.

When a big king comes to the boat, quickly check out the placement and hold of the hooks. If they’re visible and lightly hooked, a sharp yank often pulls them free.

However, anyone who tries this technique should wear a heavy glove. If the fish is deeply hooked or appears to be hooked solidly, quickly cut the leader as close to the fish’s mouth as possible. When handled in this manner, other than being tired and a little sore, king mackerel suffer minimal strain.

Most fisheries biologists agree a fish has better odds of surviving when quickly and easily released, even if the hook is still present. The fish often suffer more damage from the stress, strain and rough handling of removing a hook that’s buried deep.

I’ve caught several fish that appeared to be healthy even though they carried a hook from a previous encounter. I’ve also landed fish that continued to eat while carrying hooks after being caught earlier.

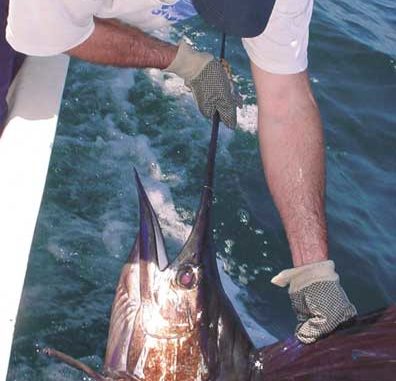

A television show about sailfish was a little better as anglers used heavier tackle and didn’t wear out the fish to the point of near-death before boating them. However, bringing the fish in the boat sooner and while they were struggling aggravated the problems associated with Strikes 2 and 3.

Even worse, these people touted circle hooks, the type of hook they removed from the sailfish. Except for getting a better picture, there was no need to bring those sailfish into the boat.

The circle hooks could have been removed while leaning over the side of the boat and leaving fish in the water.

Several states have passed legislation that prohibits bringing a fish that’s not going to be kept into a boat.

When anglers know they will release fish, they can choose a rod, reel and line outfit, plus terminal gear, tackle and bait or lures to shorten the fight and increase the fish’s probability of survival.

Alaska and Florida don’t allow anglers to pull fish that will be released from the water. Alaska also requires anglers to stop fishing once the legal limit is reached. Anglers may catch and release fish until they reach the last fish of a limit, but then they must stop fishing.

Some of our most commonly released fish include trout (speckled and gray), red drum and flounder.

Trout and flounder often must to be released because they’re too small to keep. These fish should be handled properly or they won’t recover and won’t continue to grow.

While a few trout and flounder anglers release a high percentage of their fish, more drum fishermen release fish that could be legally retained. This willingness to go beyond the regulations to protect the species is what makes them so passionate about drum at fishery meetings.

While they aren’t the final word in proper tackle for releasing fish, circle hooks are a great starting point. When used in the correct size range and fished properly, non-offset circle hooks have a high hook-up rate and a low probability of hooking a fish deeply. The great majority of fish caught with circle hooks are hooked at the jaw, near the corner of the mouth and the hook easily rotates out.

For years veteran eastern N.C. anglers have touted a rig developed by Pamlico County fisherman Owen Lupton as being excellent for catch-and-release fishing of large red drum.

I recommend his rig. It uses a circle hook with a nearby stationary sinker to quickly turn the hook into the corner of a fish’s mouth. This feature helps prevent large drum from swallowing natural baits and becoming deep hooked, which may be fatal.

The success of this rig runs well into the 90-percent range. The success has been so good, with high hook-up ratios and low deep-hooked issues, more anglers are using Lupton’s rig in smaller sizes for smaller fish.

While they’ve been used successfully for offshore bottom fishing, circle hooks still have not been totally accepted by the bluewater trolling fraternity.

With circle hooks required for natural baits during billfish tournaments, the rigging techniques to best use them should improve rapidly in the next few years. Use of circle hooks, scheduled to become a tournament regulation during 2007, was postponed until 2008.

The N.C. Governor’s Cup Billfishing Conservation Series and other tournaments saw the writing on the wall several years ago and began adding a secondary category for the most releases of circle-hook-caught billfish. In an attempt to persuade fishermen to accept circle hooks and learn to use them, this rule was added to the Governor’s Cup categories beginning with in 2005.

A federal requirement for circle hooks was issued then withdrawn for the 2007 billfish tournament season. The requirement for non-offset circle hooks for all natural baits has been reinstated for the 2008 billfish tournament season.

Unfortunately circle hooks don’t work well for all applications. Lures that use treble hooks don’t work well if replaced by circle hooks. Circle hooks work fairly well with jigs such as Stingsilvers, Hopkins and diamond jigs. Many lures often work best, even for catch- and-release fishing, by simply substituting a J-hook for a treble hook.

The bottom line is anything anglers can do to make hooks easier to remove and reducing stress and time out of water aid a fish’s ability to survive. When planning to release fish, it’s far easier to excuse pulling a hook or other mistakes that allow the fish an earlier but unintentional release.

Once a fish is fought to a bank, beach, pier or boat, anglers can employ several techniques to help ensure its survival upon release.

First, handle a fish as little as possible. Dragging a fish across the gunwale or transom, onto the bank or a pier can cause serious bruising, internal injuries, rake off its protective slime coating and seriously reduce its ability to survive.

If a fish must be handled, wear wet cotton gloves or use a wet cotton towel. Wet cotton doesn’t scrape off the slime coating as much as handling a fish barehanded or with most glove fabrics.

When holding a fish that weighs more than a few pounds, don’t hold it by the jaw or gill covers. Use your hand or arm to support its body along its length. It’s especially important to support the stomach area. A fish’s internal organs are held in place by thin membranes and tendons don’t support them well when a fish is removed from water.

Posing fish for pictures is one area where most anglers set awful examples. Large fish especially shouldn’t be held vertically by their gill plates or a lip gaff. Being held vertically may rip tendons and cause internal damage that quickly becomes a death sentence.

When posing pictures, support a fish properly, handle it carefully and return it to the water as quickly and in as good condition as possible.

Hook material also can help a fish’s survival. Hooks made of metals with no- or low-corrosion resistance deteriorate faster. Bronze hooks are the least corrosion resistant, followed by tin and nickel, with stainless steel being the most corrosion resistant. Avoid stainless steel hooks when possible.

After removing or cutting off a hook, a fish probably will need to be revived a little before it’s ready to swim off. Many small- to medium-size fish can be supported by a hand underneath their bellies while being slowly wiggled by the tail to get water flowing over their gills to revive them. Hands under a fish’s belly and around its tail give some control while allowing the fish to easily swim off when ready.

Larger fish often require a flow of water over their gills before they revive. Leaving the motor in gear at idle and slowly pulling the fish forward through the water is a good way to create the water flow and revive them.

Billfish are a natural for this revival technique as their bills become handles for anglers to hold. Just be sure to push the bill away when the fish responds and starts swimming.

It isn’t difficult to tell when a fish is ready to swim away; it will shake its head or kick a few times. That’s when it’s ready to go.

Catch-and-release doesn’t harm fish when done correctly. But handling a fish improperly while unhooking or releasing it can cause harm beyond the ability to recover.

Remember catch-and-release fishing is more than simply removing the hook and throwing a fish back into the water.

With proper handling, a released fish will recover to produce future generations that may thrill future fishermen.

Be the first to comment