Anglers have been using hooks to catch fish since the Stone Age, fashioning hooks from wood, bone, shells and horns. Stone Age men crafted fine hooks from animal bones. Native Americans made hooks from the claws and beaks of hawks and eagles. In ancient Norway, fishers made hooks from the thorns of the hawthorn bush. According to some accounts, early residents of Easter Island made their hooks from human bones.

Today’s hooks are the result of thousands of years of trial and error, a collective effort of hundreds of generations of fishers. While manufacturing methods and materials have become more sophisticated, the basic hook pattern has changed little since the first Stone Age angler dropped a hook and line into a stream and pulled out a fish.

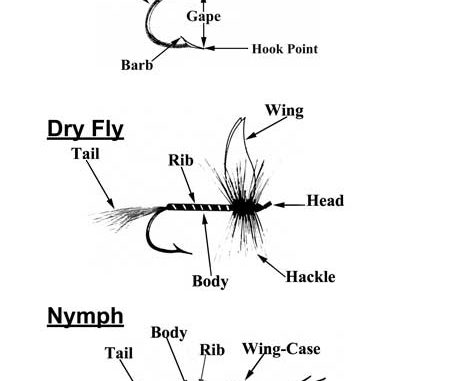

Understanding basic hook terminology is the initial part of the process of learning how to use flies to catch trout. Following is the basic anatomy of a hook:

Shank: The shank is the leg of hook, extending from the eye to the bend of the hook. The most common shanks are straight, forming a straight line from eye to bend. Some hooks have a curved up shank to accommodate certain fly imitations.

Hooks with a sliced shank have barbs cut into the shank to anchor soft baits such as worms. Shanks also come in different lengths. A 4X long shank, for example, is used for tying streamers, flies that imitate minnows and other aquatic forms. A 2X long shank is used for tying nymphs such as Hare’s Ear, Pheasant Tail, as well as wet flies, pupa, and other insect forms. A standard shank hook is used for tying Caddis, Cahills, Adams, terrestrials, and parachute patterns.

Eye: The eye is the hole or loop at the end of the shank where the line or leader is attached. Position of the eye is important when it comes to improving the hooking potential of a fly.

Straight is the standard position; other variations are turned up, turned down and parallel. A parallel hook’s shank is curved down so the eye is parallel to the hook.

Bend: The bottom or curved portion of a hook.

Hook and barb: The hook is what “catches” the fish, and the barb keeps the fish on the hook.

For catch-and-release fishing, anglers often use “barbless” hooks to make it easier to remove a fish from the hook. Most ancient hooks were made without barbs. Only after thousands of years were hooks equipped with barbs, grooves, bulges or holes.

Gape: The distance between the point and the shank.

Bite and throat: The distance from the apex of the bend to its intersection with the gape.

Hook size: Hook size is determined by the gape, not by the length of the shank. For example, a No. 14 long streamer hook will have the same gape distance as a No. 14 standard dry fly hook or a No. 14 2X long hook.

Also, in a departure from standard measurement, hooks for trout flies range in size from 0 to 32. The higher the number, the smaller the hook. Most American flies are measured in even sizes. In another departure, when hook sizes go beyond 0, (1/0 to19/0), the higher the number, the bigger the hook and the gape. A 19/0 would be used for catching sharks and other large marine fish.

Other distinctions: Hook points come in a variety of features such as knife edge, needle, short, and beak. Hook eyes also come in a variety of forms: ringed, tapered, lopped, open, needle and flattened. Hook coatings can be made of Duratin, black nickel, tin, or gold. Hook finishes can be black, black matt, bronze, blue, green or yellow.

To keep the process simple, experts suggest keeping a stock of four hook styles in the most popular sizes: a standard hook in sizes 18 to 10, a 3X long fine wire dry fly hook in sizes 14-10; a 2X long nymph hook in sizes 18-8; and a 4X long streamer in hook sizes 12-6.

That range of flies should cover about every fly you need to successfully fish for mountain trout.

Be the first to comment