Preserves not only extend waterfowl season, offer opportunities for kids to hunt and training for dogs but have saved family farms.

Wayne McDowell sloshed through shin-deep water while behind him trailed a dozen mallard decoys tied to monofilament lines, banging together like plastic drums. With one eye on the sky, he placed the decoys with serious intent while watching for early arrivals.

“It pays to get out here early because you don’t know for sure when the ducks are going to fly,” he said. “But you don’t want to miss seeing the sun come up. Seeing the sunrise over a spread of decoys is what waterfowl hunting is all about.”

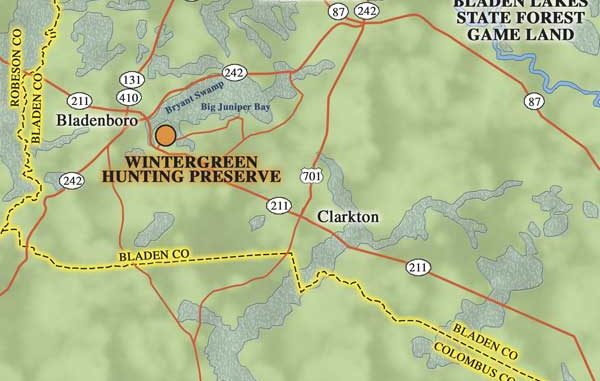

McDowell is a hunting guide at Wintergreen Hunting Preserve near Bladenboro. The hunting preserve has been in operation since 1987, but ducks are a relatively recent addition to the shooting menu.

The hunt began well before dawn, with a clubhouse full of hunters preparing for quail and pheasant hunts with handlers working pointing dogs in the morning. Tower shoots for pen-raised game birds were scheduled for the afternoon, another reason McDowell wanted to get the duck hunt underway as early as possible.

“We can hunt ducks in the morning and get in a quail or pheasant hunt after lunch,” he said. “If the ducks work well, we should have our limits by mid-morning.”

Boyce White, now 41, began operating Wintergreen at the family farm. In 1987 he was a student at N.C. State University where he took a course in game-bird production. The education gave him an idea that would help preserve the family farm for future generations.

The farm encompasses 500 acres of land in Bladen County and has been owned by his family for more than 75 years. While still a working farm with a beef-cattle operation, an increasing amount of the farm’s income comes from the hunting preserve operation. Boyce White convinced his father, Jerry White, that raising quail would enhance the farm’s income. Then he began a quail hunting preserve.

The operation was named Wintergreen for the green fields planted each winter for cattle forage.

“We now raise 85,000 quail to sell to other preserves,” White said. “We started our own preserve, and it’s been very successful. The duck side of the preserve’s operation began four years ago, but we weren’t happy with the results. It was like many canned hunts, and we wanted it to be as close to a wild bird hunt as possible. So we began using a mallard that is part wild duck and we release them so they’re essentially feral and not acclimated to people. Now, it gives us an exceptional hunt because they act just like wild birds.”

The mallards are raised in ponds that are remote from the ponds where McDowell places his decoys and hunters. The hunting ponds were cleared out of cut-over forests and fallow fields, leaving some standing oaks, sweet gums and other trees in the flooded waters.

The pond bottoms have a solid footing composed of native clay for ease of placing decoys and were constructed in a stair-step fashion, with water flowing from one pond to the next in series. Risers hold water at a comfortable level for hunting, the way most impoundments across the Southeast are constructed.

The Whites used a bulldozer to construct the pond dikes and level bottoms that had been recently logged. During the past, these areas would have been converted to pasture, left to regenerate a forest or replanted in trees. But wildlife uses are supplanting farm and producer uses at much of the coastal plain as farms try to find ways to survive the onslaught of humanity immigrating to the area.

The entire hunting operation, which now takes place at more than 300 acres of the farm, began with the clearing of just 10 acres for quail hunting. Now, the operation includes several rectangular ponds with eight hunting blinds overlooking the ponds. The ponds are approximately 2 acres in size and wide enough that shooting a duck at the opposite side is a questionable objective.

Each blind is several times longer than wide, they’re comfortable and built of plywood with bench seats with a shelf across the front for shells and resting shotguns.

“An organized blind that’s comfortable for five hunters is a great addition to any hunt,” McDowell said. “We build the blinds and maintain them, brushing them with native vegetation and camouflage netting so the ducks won’t flare from them. The ducks get wary this late in the season because they’ve been hunted fairly hard. You need to wear a face net or they’ll spook away at the shine of your face if you look up at them.”

One thing that helps keep mallards at the ponds is an abbreviated hunting schedule, with duck hunts scheduled only for Saturday mornings. All ducks get smart if they get pounded day after day.

“You have to work them just like wild ducks,” he said. “You call very sparingly and once they see the decoys, you need to tone down the calling with quiet quacks and feeding chuckles or the birds will flare away.”

As dawn grew, mallard wings ripped overhead with the sound of an airplane’s wings flaps shearing the sky, preparing to land at a runway. Quiet quacks, loud hail calls and muted feed chuckles issued from small groups and large flocks, but most of the ducks headed for the sanctuary ponds.

“If you listen to them, you can tell what mood the ducks are in,” McDowell said. “If they’re quiet, you need to use quiet calls and if they’re being loud, you need to make some loud conversation to get their attention.”

Basil Watts of Wilmington was at one pond and a short distance away at another pond was a party in another blind with guide Doug Jackson. As daylight light grew, shots taken by hunters at the other blind announced action was beginning.

“The initial reaction is to shoot at the ducks too far away,” McDowell said. “If you listen to the calling from that blind, you can hear it’s fairly quiet. The ducks have heard lots of loud calling already this year since they’ve been hunted since November. Whether it’s good calling or bad calling, calling loud or too much is the best way to keep them out of the decoys.”

A hen quacked overhead and McDowell answered with a quack. She hit the water, still quacking and even a trained retriever could hardly stand it. He stood and wagged his tail, beating it against the blind, and the duck flew away.

“I want to shoot some greenheads,” Watts said. “If the ducks are working well, I’ll let a lot of the hens go.”

The hen launched unscathed, secure from Watts’ shotgun. He was using a double-barrel 12 -gauge scattergun with Kent Matrix ammunition. He said the soft shot of the tungsten-polymer would kill ducks efficiently while protecting the barrel of his classic weapon.

“I shoot No. 3 and No. 5 shot,” he said. “For big ducks like mallards, the No. 5’s seem to work the best.”

McDowell did most of the calling, without much shooting. He stayed outside the blind while the hunters inside watched the birds work.

“If a hunter wants to bring his own dog, it’s fine with me,” he said. “But I bring my dog along if needed. I like to sit outside the blind where I can see the ducks working. I can tell the hunters where the birds are coming from and call the shot when it’s time to shoot. But if a hunter is experienced, he can also do his own calling. It’s whatever the hunter wants to do that dictates how much guiding and dog handling I do.”

Several flocks of ducks, along with singles and pairs, worked the decoys. While it was tempting to shoot, most of them appeared to be merely looking over the landing area.

“Their sanctuary pond is well over 500 yards away,” McDowell said. “It’ll pay anyone, whether it’s a preserve hunt or a wild duck hunt, to keep that in mind. Anyone with access to hunting property should leave an area where the ducks aren’t bothered. If you hunt every pond on your property day after day, ducks will move to where they aren’t pestered.”

As the daylight grew, Watts and McDowell took a few shots, but more birds stayed out of range. Still, they seemed to become more and more interested, circling lower all the time.

“You just have to be patient,” McDowell said. “Sooner or later, they’re going to commit. The worst thing you can do is start firing at them when they’re out of range. You wind up using your time chasing cripples and wasting ammunition. You’re also educating those birds and it’ll make it tougher to get them into the decoys later in the season.”

McDowell also predicted the best hunting would occur at mid-morning. After all, he had spent every weekend for several months watching the ducks, so he had the inside track. It paid to listen to him.

One particular flock with several nice drakes in it slipped down on cupped wings once McDowell began calling to them. Some ducks landed and some had their feet reaching for the water as Watts fired. Two stayed in the decoys, orange legs kicking.

“If they start landing, you want to shoot the birds in the air first,” Watts said. “The ducks that start getting up off the water when they hear the shooting will still be in gun range.”

It didn’t take long for Watts to down what would have been his standard limit of four mallards. But this was a license-controlled shooting preserve. For an additional fee, he could shoot all the ducks his wallet can stand or as many as the preserve’s pre-determined limit.

“That’s part of the attraction of preserves,” McDowell said. “You can extend your hunting season, and it’s also good training for you, your family and kids and a dog, if you have one. The later in the season it gets, the better the hunting gets because the ducks become better educated.

“You have to use all your skills, but at least you know there are plenty of birds there, and that’s what can set a preserve hunt apart from a wild duck hunt. If we don’t have any ducks, we’ll tell you that right up front.”

Jackson used his cell phone to tell McDowell his party’s hunt was finished. It was mid-morning and, as McDowell had predicted, each hunter at the two blinds had all the shooting he wanted. Jackson drove along the slippery road leading to the blind and helped McDowell pick up the decoys.

“Looks like you guys had some luck,” he said. “Did you notice how wary the ducks were? It didn’t pay to call too loud.”

Jackson and McDowell compared hunting successes while the hunters packed up their ducks, gear and shotguns into the pickup trucks. They headed for the clubhouse to check on the upland hunters and eat lunch before heading out for sampling the afternoon hunting opportunities.

“Did you have a good time?“ White asked. “We want our duck hunts to be as close to a wild bird hunt as possible.”

Watts nodded his head and smiled. His ducks were taken to the cleaning station behind the clubhouse to prepare them for cooking or the freezer. Other hunters’ birds were being cleaned as well.

“Without preserves like this one, a lot of hunters in this area of the state wouldn’t have a place to hunt,” he said. “Some people don’t like them, but to me, shooting a game bird is shooting a game bird.

“I like hunting wild ducks as much as anyone, but they’re getting tough to find. Preserves get people to buy hunting licenses and keep them interested in hunting. It helps them get out in the field with their kids and dogs. Most of all, Wintergreen is one place in southeastern North Carolina that hopefully will never become another golf course or subdivision.

“We have enough of them, but an open space where you can go hunting and that actually has game on it’s getting harder and harder to find.”

Be the first to comment