Kerr Reservoir, a.k.a. Buggs Island, may be North Carolina’s best lake for big catfish.

If you like heated arguments, it only takes one question: which North Carolina lake has the most and biggest catfish?First, you’d begin and end with just two species — blues and flatheads — because they grow larger than any North American catfish.

Then, in the Tarheel State, one would move to individual lakes, such as those on the Yadkin/Pee Dee River chain — High Rock, Tuckertown, Badin, Tillery and Blewett Falls — or the Catawba chain — Rhodhiss, Hickory, Lookout Shoals, Norman, Mountain Island and Wylie. The Yadkin lakes might even prevail because the state-record blue catfish, an 89-pound fish, came from Badin Lake. And one easily could make a case for the Neuse and Cape Fear rivers as well.

But for consistent numbers of large blues and flatheads, it would be difficult to surpass John H. Kerr Reservoir, a 48,900-acre impoundment shared by North Carolina and Virginia. Fished by anglers from both states, Kerr Lake, also known as Buggs Island Lake, probably produces more trophy-size catfish than any of North Carolina’s large lakes.

You would get no argument from Tony Small of Graham, a fisherman who heads to Kerr Lake almost every warm weekend.

Two summers ago, he visited Kerr, ready to show a fishing buddy some premier fishing for blues. He had no idea he’d encounter one of the biggest blues ever taken from the reservoir.

“My fishing buddy, Dale Eastwood, and I put our boat in the water at the Ivy Hill ramp early one Saturday morning,” Small said. “We like to get out early because it usually gets too hot for us by afternoon most days.”

Small and Eastwood were in a 14½-foot aluminum tri-hull loaded with six, stiff-spined 6-foot rods and reels spooled with 50-pound braided line, heavy-duty swivels, 40-pound monofilament leaders measuring two feet long, and big 7/0 hooks — the kind of tackle anyone needs to challenge Kerr Lake’s magnum catfish.

“We didn’t have to go far,” Small said, “just across the lake to Island Creek. We’d been over there a lot of times and had good luck with catfish.”

They headed for a large cove near the end of Mill Creek Rd.

“I like to use Carolina rigs for catfish,” Small said. “I use ¾-ounce barrel weights, then tie on a leader and hook. My favorite bait is a big chunk of (gizzard) shad.”

After putting shad filets on each rod, the two anglers lowered three lines at the front of the boat and three off the gunwales near the stern, placed the rods into holders and settled back.

“We dropped the chunk baits down at different depths, from 10 to 25 feet,” said Small, who estimated the depth at 30 feet, except for a deeper creek channel that coursed a few feet toward the cove’s middle. Small said he believes big catfish roam the channel then move shallow to feed.

“I like to drift for catfish at different depths,” he said. “That way I might catch one either moving shallow or going deeper.”

Small uses his trolling motor only if there’s no wind. He’ll slowly crawl upwind, cut off the trolling motor, then let the wind push his boat with his baits trailing just off the bottom.

“I catch blue cats mostly this way,” he said. “I’ve caught a few flatheads, but it’s mostly blues.”

While seated at the boat’s stern, watching the three back rods that day, Small noticed one of the them dip sharply. He grabbed the rod and lifted up.

“I could feel something on there, so I gave it a good yank,” he said. “That’s when the fight started.”

Small had no doubt he’d hooked into a large catfish; he just didn’t know how large it would prove to be.

“He pulled me and Dale around the cove for maybe a half-hour,” he said. “I had a hard time getting back line. When he decided to go somewhere, he just went, and we had to go with him.”

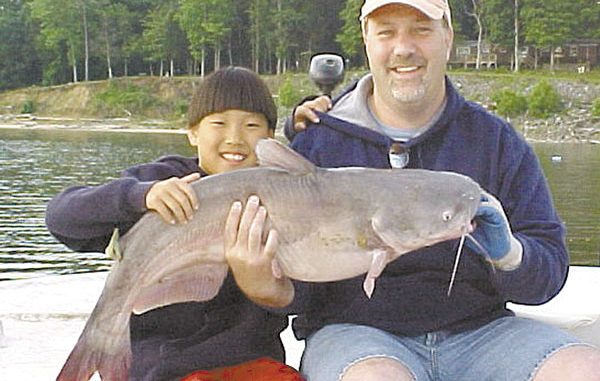

After applying back-straining pressure, pumping and reeling like he was fighting a blue marlin, Small, a master carpenter, finally pulled the big fish near the surface. His fishing buddy nearly had a heart attack.

“Oh, my God!” Eastwood said. “That catfish has got to weigh at least 100 pounds!”

Small recalled thinking the catfish couldn’t be that big, but when he got a good look at the monster blue, he knew his partner might be correct. He knew they couldn’t put the catfish, which was nearly five feet long, into his boat.

“I was afraid if we tried that we’d get overbalanced, and he’d turn us over,” he said. “We couldn’t lift him into the boat. I didn’t have a livewell either, and if I had, he wouldn’t have gone in it.”

They finally decided to pull the monster catfish to the side of the boat, grab it, then try to motor to shore. Without a rope to secure the big catfish to the side of the boat, Small gaffed the big cat’s head.

“Dale held the gaff and the fish while I drove the boat back across the cove,” Small said. “I thought we’d never get to the shore. It took forever, but I didn’t want to go too fast. I thought he might get off.”

Eastwood held the gaff as Small slowly motored across the lake to the Ivy Hill ramp. Once they beached their boat, they dragged the huge cat onto the shore.

“We had some scales, so I threw a rope over a tree limb, then tied the scales to the rope,” Small said. “When we pulled the catfish up, (the scales) showed it weighed 87 pounds, eight ounces.”

That was an unofficial weight, because Small and Eastwood skinned and fileted the catfish on the spot, then took the filets back to Graham for a neighborhood fish fry.

“That’s what we always do,” Small said. “We eat the catfish we catch at Buggs. I don’t know how many pounds of filets we got from that fish, but it was a lot.”

Neither of them knew they’d dissected Buggs’ No. 2 blue cat of all time, trailing only a 92.28-pounder caught June 29, 2004, in Bluestone Creek by Roxboro’s William Zost — a catfish that once held Virginia’s state record.

Small fishes today mostly with another Graham resident, Jerry Crowder.

“We go pretty much every weekend,” he said.

Small and Crowder fish where they find fish biting. They usually don’t fish the Staunton River and its feeder creeks above Clarksville, Va., where many anglers hunt monster catfish, even though North Carolina and Virginia honor reciprocal fishing licenses.

“We go to Ivy Hill or Henderson Point mostly,” Small said. “We just jump around, trying to find a good spot.”

One tip Small has for novices is to look for freshwater mussel beds along the shoreline.

“If we’re close to the bank in eight or 10 feet of water and see mussels on the shore, I’ll take my aluminum (boat) pole and punch down to the bottom,” he said. “The (end of the) pole will feel like it’s crunching stuff — mussels down there.”

Why is the presence of mussels important?

“Blues and flatheads eat mussels, the shells and everything,” Small said. “I’ve caught catfish with a pound of shells inside ’em.”

Small said 95 percent of his catches are blues.

“I like drift fishing, and that’s what we usually catch,” he said.

To find good spots, he simply watches his depth-finder.

“We’ve caught most catfish in 15 to 30 feet of water,” he said, “although I have caught ’em in 80 feet.

“We normally try to keep the baits just off the bottom, but we stagger (the depths) when we first start drifting. We drift channels mostly, anywhere we can see a big concentration of fish. We use live or cut shad.”

A typical summer day begins with Small and Crowder on the lake at 7 a.m. They fish for about three hours, then head for the shore, some shade and rest. About 6 p.m., after supper, they head back out for a session of night fishing.

“We might set a few jugs (noodles) out while were resting,” Small said.

Small said deep-fried battered catfish chunks (½- to 1-inch square) are the best reward for anglers.

“Just don’t cut too close to the skin when you filet,” he said. “You don’t want any of that red streak (of meat) in your filets because it tastes strong.”

Be the first to comment