Mackerel are prime candidates to help teach Charleston-area fishermen the basics of fly-rodding.

Spanish mackerel visit South Carolina’s nearshore and inshore waters during the summer, and you can almost “bank” a few each trip in July.

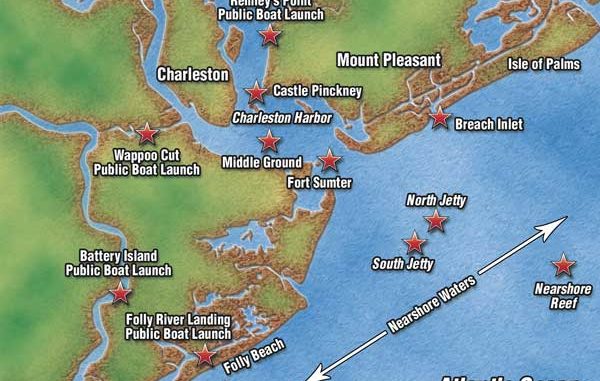

Charleston Harbor is a great place to start looking for Scomberomorus maculates, the smaller cousin of the king mackerel, when they make their frequent high-arching jumps out of the water in pursuit of baitfish.

And unlike other species, strong currents don’t hurt the action; when you’re targeting Spanish, the faster the current the better.

Tidal currents run hard in the harbor’s shipping channel, and just off this channel are favorite haunts of Spanish known as the “Middle Grounds” and “Chutes Folly.” In this area, the channel’s depth goes from 50 feet as it approaches Castle Pinckney to only 12 feet deep. Capt. Mark Phelps of Shore Thang Charters knows this is where Spanish likes to drive and trap the bait against the bank, using current or wind conditions to their advantage.

Phelps specializes in fly-fishing and has guided in the Florida Keys, but he calls Mount Pleasant home and routinely rings up impressive redfish tallies. When Spanish mackerel invade coastal waters, he’s excited about the action he can put his clients on, and he knows that summer saltwater fishing is at its peak.

While targeting schools of Spanish in the harbor, he knows the chance exists of running into bluefish, ladyfish and occasionally a jack crevalle.

Cruising into the Chutes Folly area, Phelps picks a Ross Worldwide Essence FW 9-foot, 8-weight rod with a Ross reel spooled with 8-weight, sink-tip fly line with a clear end. The first 15 feet of the line sinks, and the rest of it floats.

“This sink-tip helps to get the fly down quick,” Phelps said, “and the Spanish think that it’s the (back) half of a previously thrashed bait, and they strike it.”

Spanish mackerel move inshore when the water temperature reaches 79 degrees. In July, Spanish average 12 to 20 inches long and run in schools, but larger fish are often available.

“The biggest Spanish mackerel move up the coast earlier, like May and June, and these are typically females,” he said. “You can look at the Spanish mackerel records at the Folly Beach Pier to help understand when the heavier Spaniards come through.

“The Spanish mackerel come here on the Gulf stream and then turn inland, so they might actually arrive here before somewhere like Savannah.”

Getting the jump on mackerel can often mean an early rise in July to beat the heat that arrives at mid-day. Phelps reads the water before the sunrise and get a bead on small bait that’s jumping out of the water as if being pursued. that usually means the favorite food for Spanish: glass minnows.

Outboard motor noise can spook Spanish, so Phelps likes the engine cut off in order to drift near to the fish. He looks for diving birds like royal terns and common seagulls; their presence often signals that feeding Spanish are nearby. Pelicans do not typically dive over the smaller baits that Spanish prefer, so you can rule them out.

When he sees bait fleeing, he makes a false cast or two before landing the fly where he last spotted the bait. Then it’s strip-strip-strip of the line and a hookup — right at sunrise.

Once subdued, most fishermen will swing a Spanish into the boat — unless it’s a very large one. Nets, well, they don’t win battles against the sharp teeth of a mackerel.

Typically, hooking and fighting one or two fish out of a school of Spanish does not upset them, whereas running an outboard motor close to them will often cause them to sound and disappear. When fly-fishing, remember to use stealth, and plan your angle of approach so you can place your fly ahead of the school.

As the summer progresses, another baitfish arrives on the scene, and mackerel take notice.

“Spanish Mackerel flourish and grow a lot during the summer, and they love to eat small menhaden,” said Phelps, who believes that Spanish have the great vision of a tuna and uses 30-pound fluorocarbon leader for more strikes. Yellow and white Clouser Minnows work the best in Charleston harbor because they imitate menhaden.

Water clarity can affect fishing options. “In clear water conditions, I like an olive-and-white Clouser Minnow, and for overcast days or dirty water, I prefer a pink-and-white Clouser Minnow. Electric chicken colors also work well,” Phelps said. “Sometimes, I switch to a Gurgler popping fly, which has small holes that water passes through, and other times I throw a Crease fly, which lays on top of the water so I can twitch it.”

Capt. Chris Keen of Keen Eye Charters in John’s Island weighs in with his choice of flies.

“Anything that mimics a flashy glass-minnow pattern is okay with me, and the Spanish are likely to ignore everything else when they are keying in on these baits,” he said. “My favorite flies are a chartreuse-and-white Clouser Minnow, Kirk’s fly spoon and Cowens Albie Anchovie.”

Keen carries a 7-weight G.Loomis rod paired with an Orvis reel. He also uses sink-tip fly line. “Sink-tip is more versatile than a floating line,” he said “If you strip it fast enough, it doesn’t sink anyway, but since the larger Spanish are underneath the bait a lot of the time, you want your fly to sink.

One of Keen’s tricks is to “dead stick” the fly, casting toward the Spanish, stripping four times before shaking the gathered line back out of the rod tip, allowing the current to take the fly down 15 feet or so for a natural presentation. Keen uses a leader of four to five feet of 50-pound mono and never uses wire. Monofilament holds up, but “cut-offs are part of the game when going for Spanish mackerel,” he said.

“Anglers enjoy about the same amount of success using a fly rod when targeting Spanish as they do using light spinning tackle. When clients fly-cast, I remove all obstructions from the boat or cover what can’t be removed with a towel.”

Be the first to comment