Calm winter days with a warming sun can produce big catches of weakfish.

Even in the dead of winter, there can be some lively “gray” days for fishing at North Carolina’s southeastern coast.

The sun smiles, melting the clouds and fills the air with warmth. The wind gods even seem to take a break, making the ocean’s surface seem as smooth as silk. Anglers must be prepared to take advantage of these not infrequent Indian summer/winter weather days.One angler always prepared for a break in cold weather is Shane Snow, one of the captains for Fish Witch Charters. He usually operates the family business’s smaller boats, a 25-foot Carolina Skiff, the Little Witch, or a 25-foot-long offshore boat, the S.S. Fish Witch. His dad, Carl Snow Jr., pilots a 48-foot Henriques, the Fish Witch II.

“I caught a lot of roe mullet last fall,” Shane Snow said. “I removed the roe and cut the mullet into fillets and salted them. Put them in the freezer preserved them, but the salt keeps them from freezing. Salted mullet fillets make the best baits you can have for catching gray trout.”

Gray trout, also know by their commercial name of weakfish, routinely have made strong showings in the waters where Snow fishes offshore from Pleasure Island. Sometimes the gray trout are small and must be sorted through to catch a limit of keepers. But the past couple of winters, the fish have been exceptionally large.

“We catch a few fish topping 4 pounds during most trips,” he said. “Most of the fish will weigh between 2 and 3 pounds, and we’ll catch an occasional, honest 5-pounder.”

While anglers in the northeastern and middle Atlantic states catch most of the adult fish, which can reach two or three times the weight of the fish Snow catches, these fish spawn in North Carolina waters a few miles offshore of Cape Hatteras, fisheries biologists note. The big brooders then migrate north, leaving the smaller, younger fish for Tar Heel anglers. These small fish can be abundant.

“Some years there are more gray trout than others at Carolina Beach,” Snow said. “But the winter of 2007-08 has been a banner season. Most trips everyone has been catching a limit, then we catch and release all anyone wants until they get tired of catching them.”

Fishing with Snow was his friend, Jesse Christopher, who is foreman of the Snow marine-construction business. The fact the two veteran anglers work together helps them stay ready for last-minute trips. They keep the 25-foot skiff ready and waiting at the Carolina Beach waterfront when the gray trout are present in waters just offshore.

“This is going to be a good night for catching grays,” Christopher said. “There are only a few nights like this each month when it’s calm and the moon is out.”

Indeed, a full moon was already rising as the Little Witch left the family dock at Carolina Beach. The sun was beginning to set, and the sky was showing grayish blue as the Snow checked the speed of his boat in response to the beeping of his GPS unit.

“This is the spot,” he said. “The gray trout have really been biting at Sheepshead Rock.”

Snow watched the depth-finder screen for a few moments as Christopher readied the anchor. Once Snow found what he was looking for, a nod of his head to Christopher sent the anchor to the bottom. The anchor dug into the sand, and the boat swung against the current, the line creaking against the cleat as it came taut.

“There’s always some current, even this close to the shore and without the wind blowing,” Snow said. “If you don’t get your anchor course right the first time, you can pick up the anchor and make adjustments the next time you drop it.”

On the depth-finder screen, Snow pointed to schools of baitfish at the edge of the rock outcrop. He said sometimes he sees larger marks that indicate gray trout, but what he was trying to find were baitfishes.

“If the bait is there, the gray trout are there,” he said. “It looks good down there, so we’ll cut some bait.”

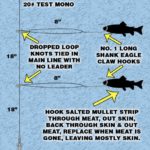

It was still light as he started slicing mullet fillets into strips from the dorsal to the ventral side. The strips were about 3/8- to ½-inch wide. He hooked the strips through the meat, then through the skin, back through the skin, then out of the meat side again.

The bait folded neatly into the bend of a No. 1 long-shank hook, leaving the point exposed. Two baited hooks were used on each double-dropper rig and a 3-ounce sinker took them quickly to the bottom. The two dropper loops were tied directly from the 20-pound test monofilament fishing line from each rod, and the sinker was tied with a surgeon’s loop to the end of the line. One dropper loop was tied 18 inches above the sinker and the second dropper loop was tied 18 inches above the first dropper loop. The loops presented the hooks about 8 inches from the dropper loop knots.

Snow uses bait-casting gear when he fishes on the bottom for gray trout. But the rods and reels are extremely light so they don’t impair the anglers’ sensations when feeling the fight of the fish. He uses Penn 940 reels and 6-foot, medium action Key Largo rods and sets a fairly heavy drag.

“Some people say gray trout have soft mouths,” Christopher said. “But if you let any slack get in the line, that’s when you’re going to lose fish. We keep the drags tight enough so that the line stays taut.

“When you’re reeling in two gray trout that could weigh 8 or 10 pounds combined, you can’t land them with a reel drag that’s set too light. If they’re hooked lightly, they’re going to pull off, no matter what you do.”

It wasn’t dark when Christopher hooked the first trout of the night. Soon gray trout, ringtails (spottail pinfish), bluefish, sea bass, tomtates (red-mouthed grunts) and oyster toadfish were coming up from the bottom. But approximately one-third of the catch consisted of gray trout. They bit well for a short while before slacking off.

Two boats anchored nearby showed bright lights from their T-tops for a few minutes before leaving. It was getting too dark to see well for navigation, despite the moonlight. A short debate ensued among the two-man crew of the Little Witch before they decided the anglers aboard the other boats likely didn’t have limits of gray trout. There hadn’t been enough activity, accompanied by whoops of success. The more likely reason for their leaving was that it was getting too dark for safe navigation for those of less experience, despite the moonlight.

“Most anglers want to get back home through Carolina Beach Inlet before nightfall,” Christopher said. “It’s almost as if they’re afraid of the dark. But it’s a full moon night, and that’s when the grays bite the best.

“The inlet can get rough, especially on a northeast wind and a falling tide. But it should be calm tonight because the water’s so slick.”

“Even when there’s no moon out, I make my own moon,” Snow said. “I shine some really bright lights down toward the water from the T-top or from my tower if I’m on the S.S. Fish Witch.

“If you’re a little bit off the fish, you can cast around and find them. Once you start hooking them and reeling them in, the school moves closer to the boat to follow the hooked fish. The light helps them see and holds them right under the boat. Where you were only catching a few moments before, you might start catching two fish on every cast.”

But when the first place they fished didn’t produce the results Snow and Christopher wanted, they moved the boat and re-anchored a few yards from the first spot. Soon the magic of the moon or perhaps their artificial lights changed things dramatically for the better.

Christopher began hooking pairs of gray trout almost every other drop to the bottom with his baited hooks. Snow was hooking just one gray per drop, often accompanied by a ringtail or sea bass, so he moved nearer the front of the boat where Christopher was having better luck.

“I usually wait until I have two fish on before I reel up,” Christopher said. “If there’s one down there, there’s got to be another one.”

“It also helps to be fishing at the right spot on the ledge,” Snow said. “Sometimes they hit best on one side of the boat or the other, and sometimes they bite better at the front of the boat or from the stern.

“Where you drop your baits from dictates where they’ll land on the bottom. You don’t want to set up the boat so it’s right on top of the ledge where you can get your rigs hung up.

“You want to fish to one side of the ledge, and that’s where lots of fishermen make their biggest mistake. They have a number for a piece of structure, such as a ledge, wreck or artificial reef structure, and they fish the structure they find at that number. They get hung up over and over, become frustrated and leave for another spot when all they have to do is move to the side of the structure.”

While a lot of gray trout anglers use landing nets to boat their fish, Snow and Christopher grabbed the line and hauled their fish in hand over hand or simply lifted them into the boat with their fishing rods, keeping their thumbs on the reel spools to stop them from revolving as they hoisted the fish.

It took a stout rod to lift two wriggling gray trout over the side without breaking. Some rods won’t withstand this test of stamina and durability, including some expensive graphite rods that won’t lift heavy fish over the side without snapping. The average king mackerel live-bait rod surprisingly doesn’t have enough backbone for the job, but a saltwater rod made especially for deep jigging works well.

Landing nets actually reduce gray trout fishing time when anglers are using double-hook bottom rigs. One reason is getting a pair of 4-pound gray trout into the same net likely will result in at least one of them being beaten off the hook by the net. The other is that hooks tangle in the mesh. Getting hooks out of the net is difficult enough during daylight hours, but at night it can take even more time to extract them.

Snow said gray trout prefer relatively warm-water conditions when speaking of fishing during winter. Grays bite well as long as the water temperature remains in the upper 50s to low 60s. This condition occurs in November and December during average N.C. winters. Then the water temperature cools down so much the gray trout leave, and the sea bass, sea mullet and ringtails take over bottom structure within 3 miles of the beach. But after the coldest part of midwinter, which occurs from approximately mid December through mid February, the water begins to warm again, and gray trout activity correspondingly increases, relative to the rise in water temperature.

“Sometimes they run as well as in the first part of winter, and sometimes they don’t,” Snow said. “It all depends on the water temperature, and the baitfish showing up on the structure. The only way to find out if they’re there is to go out and check all the gray trout hot spots.”

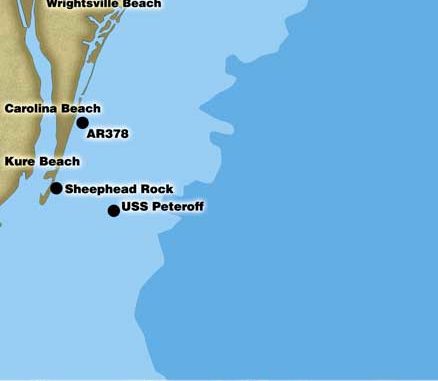

Gray trout may be found at any hard structure area between 17 and 60 feet of water near Carolina Beach.

Snow fishes for them at the Condor, a Civil War boat wreck located near Fort Fisher, another wreck named the USS Peteroff, and the 60-foot deep dredge hole just offshore from the Confederate monument at Fort Fisher.

The dredge hole covers a large area and easily can be found by anyone with a depth-finder cruising offshore from the boulders placed at the Fort Fisher’s shoreline to slow beachfront erosion.

Another popular place for catching gray trout is at AR 378, also known as the Phillip Wolfe Reef.

Be the first to comment