Coastal rivers swell with shad during the spring, and winter-starved catfish are some of the first to feast on the banquet.

Even though winter never really gets a good grip on the Lowcountry, the lengthening days of March have a feel to them like none other on the calendar.

The air smells clean, and the warmth of the sun on your skin is as comforting as a blanket to a 4-year-old. While the woods and swamps seem stark and lifeless, pockets of color from yellow Jessamine are a visual reminder that spring is coming.The only problem with the coming of spring is its trickery. The pleasant temperatures and sunshine welcome anglers, but the physics of energy and water keep the fish on a different schedule.

Even though air temperatures have warmed, there is a delay in the heating of water. You could have a week of 70-degree days in March — up from the 40s of previous days — but the water temperature may only nudge up into the 50s. It is enough to get some fish species active, but not adequate to get the entire community biting.

Fortunately, not all fish have a fondness for warm water like tarpon or bonefish. An increase of a couple of degrees from winter lows can get some species on the move. Two of those species are shad and blue catfish. A cause-and-effect relationship exists between these two early-spring movers.

Shad are anadromous fish —they spend the majority of their lives in saltwater but migrate into freshwater to spawn. Along the Atlantic coast, lengthening daylight and a rise in the temperature of coastal rivers prompt Hickory and American shad to begin their migration upstream from the ocean.

The adults attempt to move far upriver to freshwater areas where they spawn and then die. Juvenile shad are hatched and move downstream as they mature. Eventually reaching the ocean, they remain offshore for several years before returning as adults to repeat the spawning process.

This annual cycle has played out over the millennia. Although blue catfish haven’t always been present in coastal rivers, they have learned to tap into this moving bounty. Anglers who discover the phenomenon will find some of the best catfishing in the state, and at a time when most fish are still sluggish.

“In some years, the action never ends,” said Capt. Tommy Scarborough of Georgetown Coastal Adventures (843-546-3543), one of the few guides who crosses over between freshwater and saltwater species.

“The catfish bite normally picks up in February when the shad start running,” he said. “It is really good in March and April and can continue until the menhaden begin to move into inshore waters.

“When you are thinking about spring, I can tell you, the bite will be on.”

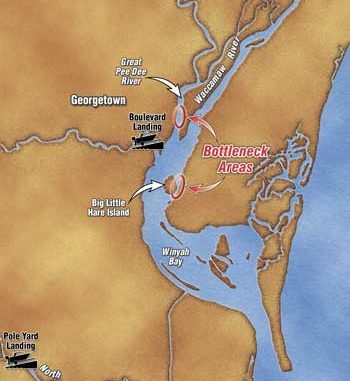

Scarborough concentrates his efforts in the Santee River south of Georgetown and in the Pee Dee and Waccamaw rivers right outside the city. The easy way to describe his fishing area is to find U.S. Hwy. 17.

Except where listed in the S.C. Department of Natural Resources Rules and Regulations booklet, U.S. Hwy. 17 is the dividing line between freshwater and saltwater for regulation purposes. Freshwater regulations apply for waters lying upstream of the line, and all waters, including streams, tributaries and rivers, downstream of the line are under saltwater regulations.

“Under average conditions, good catfishing can be found on either side of the freshwater and saltwater dividing line,” Scarborough said. “If there is a drought and a reduced amount of freshwater coming downstream, the saltwater moves farther upstream and pushes the cats upstream with it.

“On the flip side, if we have been getting a lot of rain, freshwater will move far downriver, and the catfish will move with it.

“I have caught catfish as far down as Muddy and Winyah bays below the Pee Dee and Waccamaw rivers and all the way down to the ICW (Intracoastal Waterway) on the Santee River.

When the bait starts moving in, it’s like being in a buffet line for the catfish. They move downstream as far as the salt will let them, so that they position themselves to be the first person in line.”

When it comes to catfishing in coastal rivers, especially during the spring, Scarborough said most fishermen have it all wrong.

“Most people think of catfishing as setting up over a deep hole and dropping down a stinky bait,” he said. “The blue catfish that are homing in on these runs of shad are actually very bait-oriented. You are not fishing exclusively deep holes like you hear for catfishing.”

The key to finding catfish is concentrating on areas where bait gets concentrated.

“As the shad push upstream, there are areas at Winyah Bay and in the Santee River that force the fish into bottlenecks,” Scarborough said. “The bait gets compressed at these spots, and the blue cats just wait there for it.”

For anglers interested in finding catfish, you have to have an idea where the saltwater is, then find the bottlenecks.

“A typical bottleneck area that everyone can see is located right outside of Georgetown,” Scarborough said. “Heading north on Hwy. 17, if you look upstream when you cross the first bridge, a perfect example is the old bridge to your left. As the bait moves upstream, this is one of the narrowest areas of the river.

“Farther downriver along the Hobcaw side of the river, Big and Little Hare islands are two more good spots. I’ve been fishing here and caught 20- and 30-pound redfish right next to some big catfish.”

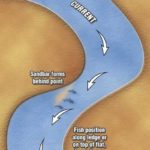

The tight twists and turns of the Santee make bottlenecks a little different. Scarborough said they exist in the form of primary and secondary sandbars affiliated with bends.

Sandbars naturally form in the back eddies of hard turns, normally between the hard current and the heel of the turn. The catfish position themselves right on the edge of the current, waiting for shad to pass by.

“As the shad move upstream, they are following the current and taking the shortest routes,” Scarborough said. “For a catfish, all he has to do is wait right along the edge of the hard current, and the shad move directly past him. The key is finding where along the ledge the catfish are lying.”

You have to think in a 3-dimensional format when trying to visualize where the catfish will position themselves on bottlenecks. They can be located along the ledge, at the bottom hiding behind a hump or even up in the shallower water above the ledge.

“The blue cats will chase bait,” said Capt. Dan Scarbor-ough, Tommy’s brother. “They could be deep or shallow.

“What I do is initially set up on the break line. I anchor the boat right over the edge and then make casts from there. I’ll make a long cast up into about six feet of water. The next cast will be a little deeper. The third will be out of the back of the boat right on the break.

“The last cast I make is out into deeper water,” he said. “This bait usually slowly washes its way from the diagonal position from the boat right into the bottom of the ledge.

“With these four rods, you have all of the depths covered. If the bite is up on the flat or out in deeper water, just move the boat to take advantage of it.”

Scarborough prefers the incoming tide when fishing the Pee Dee and Waccamaw. He feels that the bait stages as the tide switches from ebbing to flooding, and then moves up en masse with the rising water. On the ebbing tide, fish will be still be moving upstream, to some extent, but he feels they trickle through rather than move in larger schools.

“I don’t feel like the tide is as big of an issue on the Santee as it on the Pee Dee and Waccamaw,” Scarborough said. “Even though the tide causes the river to move up and down, the current for the most part is moving downstream around the points and turns.

“If you are on a stretch of the Santee River where the tide exceeds the current, just switch to opposite side of the point or turn.”

An attractive feature of catfishing in coastal rivers is that fish are abundant and can get quite large.

“Blue and flathead catfish populations in the Santee, Pee Dee and Waccamaw rivers are extremely robust and under utilized,” said Scott Lamprecht, a fisheries biologist with the SCDNR in Bonneau. Small blue catfish dominate portions of each river, but catches of 30- to 50-pound fish are certainly possible. The SCDNR encourages harvesting every catfish caught in these systems because the fish are non-native, and their populations have displaced native fish species.”

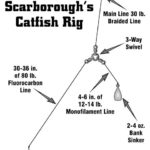

Given that some of these river catfish can be some real brutes, Capt. Tommy Scarborough doesn’t skimp on tackle and rigs. He prefers to use a 6 1/2- to 7-foot, medium-heavy Ugly Stik rod with a reel spooled with about 300 yards of 30-pound Fireline braid.

“I like to have a rod that has some backbone to get the job done when you need it, and you’ll value having the extra line when one of these fish makes a run downriver,” Scarborough said.

Off the main line, Scarborough said anglers could use a Carolina rig, drop-loop rig or a 3-way swivel setup. He usually opts for the latter because it reduces twisting of the sinker and bait lines.

For the 3-way swivel, he drops a 2- to 4-ounce bank sinker on 12- to 14-pound test monofilament off of one eye. He said that if you have to use more than a 4-ounce weight, you are fishing in the wrong spot. Further, because the sinker is what typically snags on debris, the lighter line allows you to break off the cheaper sinker while still retaining your hook and 3-way swivel.

The hook is dropped off the other eye of the swivel on a 30- to 36-inch piece of 80-pound fluorocarbon. A No. 7/0 to 8/0 circle hook finishes the rig.

“A lot of people laugh at me for using fluorocarbon line for catfish,” Scarborough said, “but I do not use it for the reason they think. I use it because it has low stretch and is super resistant to abrasions — not because I’m worried about making the line disappear.

“A catfish will roll when hooked, and when he gets those motorcycle handlebar spines that stick out from his side on your line, you had better have something that can take it.”

Scarborough is as particular about his baits as his tackle.

“I treat my catfish baits like I’m going to take them home to eat for dinner,” he said. “I try to get the freshest baits possible, and I keep them iced down.”

The primary bait is shad, which is not surprising. Scarborough prefers a buck shad to a roe shad because the meat seems to be firmer and produces more durable fillets.

He uses fillets unless the “picker” cats, as he calls catfish in the half-pound range, are troublesome.

“You can tell the picker cats are a problem if your rod tip looks like it is being shot with a machine gun,” Scarborough said.

If the small catfish are a nuisance, he cuts shad into steaks, which takes the pickers longer to destroy.

“If you slowly approach shad fishermen working nets on the river, you can usually get some bait from them,” Scarborough said. “This is especially true if they are catching a high buck-to-roe ratio.

“You can also go to the fish houses for bait. One way to reduce your costs for bait is to ask if they have any “cut roes,” which are female shad that they’ve already cut the roe out of.”

Scarborough will also use menhaden later, when it becomes available. He makes a diagonal cut from the dorsal fin down the anal fin and uses both pieces of bait. He hooks the head chunk from the chin out through the top of the head and the tail nugget in the narrow part. He does remove the tail fin to reduce twisting the line.

“No matter whether I’m using menhaden or shad, I scale all of my baits,” Scarborough said. “I feel that you get better hook penetration with a scaled bait.”

Be the first to comment