May is blue marlin season for North Carolina’s bluewater big-game fishermen.

David Dodsworth wanted a blue marlin, so he went to the best place at the right time, fished for a week and got his marlin.Dodsworth tests big-game tackle for his company, Offshore Pursuits, on fishing expeditions from Canada to Australia.

He chases giant bluefin tuna off Prince Edward Island, Cape Cod, Hatteras and Morehead City, and once, he caught a giant tuna on spinning tackle — “Which I’ll never attempt again,” he said.

“I’m coming to Hatteras to try out some new tackle and methods on blue marlin,” he said.

Dodsworth’s plan was to pull big baits — to discourage dolphin — and alter the array of tackle from seven 50- and one 80-class rod-and-reel combos to four of each. The baits on the 80s would be horse ballyhoo or other big meat baits on big, flat, skirted heads and a mix of skirted jigs and/or big baits matched to all the tackle. The 80s would carry 125-pound line, and the 50s also would be bulked up.

To avoid wahoo, he’d fish only on top, and to avoid yellowfin tuna, he’d avoid dredges or other gear that mimic balled baitfish. And he’d look for still waters that run deep.

Hatteras Village is five easy hours from Raleigh, and Dodsworth’s plan was to be at Oden’s Dock at 6 a.m. to board the Tuna Duck.

The wind blew hard on the morning of April 28 and would get worse. Capt. Dan Rooks suggested that Dodsworth wait until an oncoming front passed.

“The boats out there are reporting growing storms that will be worse by the time we reach blue water,” Rooks said, leaving the option to Dodsworth, who decided he’d rather go out and fish as long as he could, then return when the storms got too bad.

Rooks steered that day toward the Rockpile, east of Hatteras Inlet, to look for good water, then out to the edge of the shelf, and finally southwest along the edge trying to get away from the growing storms. By the time he had put out eight large trolling baits (two on each rigger, plus two flat lines and a shotgun from topside), the sky had darkened, the wind was suddenly building, suddenly waning, then quickly rising again. Black storms spread and intensified in every direction.

The Tuna Duck gave up cutting through the growing seas and began trolling its big baits between wave ridges in ever deepening troughs. Dodsworth wasn’t fazed nor ready to leave quite yet.

At once, four rods leaned hard over, but Dodsworth responded unruffled. One after the other, he brought in all four gaffer dolphin. That burst of action was a consolation prize; the increasingly large seas ended the fishing day.

The next day, winds were strong out of the northeast, causing a no-go, but Rooks was able to steer out a day later as the weather quickly abated.

Radio chatter indicated that other boats had raised several blue marlin, with a few fish caught and released.

Billfish action happens suddenly and unexpectedly.

In mid-afternoon, a blue marlin rose and lunged at six baits, one after another, without hooking up, then turned away grandly — as though proud of a great trick. It was over in a minute or two.

Rooks was booked, but Capt. Steve Coulter on the Sea Creature was open on Dodsworth’s final day.

Blue marlin partied everywhere.

Sea Creature was trolling along a weedline in a 3-knot current in 73½-degree water when the radio crackled. Gambler had released a 500-pounder and lost another. That boat was inshore in a 1-knot current at 75 degrees, apparently in a Gulf stream eddy above a wreck at 175 fathoms.

Eddies appear stationary compared with the fast-moving Gulf stream, but eddies can mean blue marlin, and Sea Creature raced westward.

With baits in the water, it wasn’t long before a blue marlin found them and did the right thing. Dodsworth took the rod while the fish took command at the other end. Half a spool down, the big fished jumped the line, leaving 10 feet of unseen chafe that later would part, but not before giving Dodsworth and everyone aboard a workout.

Still, the day wasn’t finished. A second blue marlin soon slashed the baits but failed to hook up. Fifteen minutes later — perhaps it was the same fish — a blue marlin rose into the baits. This time, the mate lifted the rod to make the missed bait look like an escaping baitfish and dropped it back, teasing the fish into hitting again and finally hooking itself.

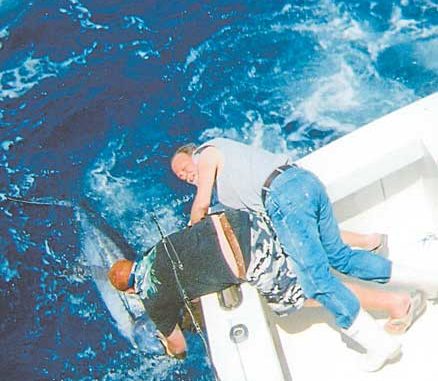

The fight began on a 50-class outfit. Ninety minutes later, the fish quieted down, seemed to give up and came in as dead weight.

The marlin, estimated at 400 pounds, had wrapped itself in the wire leader and almost drowned. It was as exhausted as Dodsworth after the fight on light tackle.

After Dodsworth cut the wire, the fish was patiently revived and swam off.

Dodsworth had his big blue marlin.

Gulf Stream eddies like the one that held Dodsworth’s fish are prime locations for blue marlin. Capt. Mike Romeo of the Gannett has some other ideas.

Romeo said he looks for changes in water color or temperature, especially at a current edge. He likes finding locations where Gulf Stream water in the mid-80s, flowing northward, meets cooler southward-flowing Labrador currents, creating a rip at the edge and dropping the bluish water temperature to 74 or 78 degrees.

“Low to zero current is best,“ he said, referring to a circulating eddy that remains fixed while other currents flow around it. When he starts his search, Romeo begins at 100 fathoms and follows the temperature trail.

If those conditions are inshore, he follows the good water inshore.

“You can find blue marlin in 50 fathoms sometimes,“ he said. “The Rockpile and other structures hold baitfish. So do the rocks seaward of Diamond Shoals light tower. I also fish the 880 break 35 miles south-southeast of the inlet. The fish aren’t always on structure, but somewhere near it, so you have to troll wide.”

Romeo generally pulls baits along the 60-, 80-, 100-, and 200-fathom breaks, working downcurrent, especially when blue water or blended water is moving over structure.

Blue marlin don’t like to fight current to hold position near baitfish; that’s why Romeo trolls downcurrent where there is a current or in eddies with no current. He finds current rips by marking sargassum weedlines. Sometimes, sea birds mark baitfish.

“You have to pay attention to everything,” he said.

Romeo fishes for blue marlin with horse ballyhoo, big squid, or Spanish mackerel dressed with an Ilander or Chugger. Some fishermen prefer pure artificial lures to cover lots of water, but Romeo likes natural baits fished slowly and deliberately.

“The new NMFS rules require circle hooks on natural marlin baits,“ he said, “but how do you rig a ballyhoo with a circle hook, except with a cradle? A lot of skippers are still figuring that out.

“We can continue to use J-hooks on artificial lures.”

Some skippers have stopped trying to rig ballyhoo with circle hooks because it’s time-consuming and awkward.

Dodsworth’s plan was a good one, Romeo agreed. He knew what not to do.

Normally, Romeo and other offshore skippers want to keep their guests fired up with action, and tuna and dolphin on 50s provide enough action to keep everyone happy. But tuna, especially, come up from down deep when they think baitfish are being balled by predators, and that’s what a dredge mimics.

Romeo has mullet dredges and ballyhoo dredges, and he fishes up to three tiers of dredges to roil the water for tuna — and later in the year for white marlin.

But dredges don’t work, he said, if natural bait balls aren’t around, such as in the spring. In addition, big baits can discourage small fish, but the won’t discourage blue marlin.

“Have you seen the size of a blue marlin’s mouth?” he asked.

No wonder they’re hard to hook.

Be the first to comment