Flooding fall tides open up some great hunting in the Lowcountry.

Fly, damn it! Shooting them is easy; the toughest job with marsh hens is making them fly.

Normally hidden from sight in thick marsh grasses, literally thousands of marsh hens, aka clapper rails, go unnoticed by fishermen and boaters all year, only occasionally revealing their presence with ranting calls of “kek, kek, kek, kek, kek, kek.” But when the autumn “spring tides” are super high, and the rising water covers all but the tallest Spartina grass, it’s game on.

Hunting marsh hens in South Carolina’s Lowcountry salt marshes — one of the most popular shooting venues of our southern forefathers — is way under-exploited nowadays. The birds are still there and just as easy to hit with a shotgun as ever, but since poling a boat takes both a little muscle and skill, not as many hunters ply the marshes. Those who do often use light, canoe-like boats or jonboats and occasionally stretch the rules about shooting while under power.

The rules for hunting marsh hens are similar to those for other migratory waterfowl, requiring the forward motion of a boat under power to be ended and the motor turned off before birds may be shot. Thus, hunters can prowl flooded marshes looking for rails, but when they’re spotted, forward progress into shooting range is by pole, paddle or oars. Unlike ducks, however, lead shot is permitted because rails are not considered waterfowl, but rather migratory birds like doves, woodcock and snipe.

In those bygone marsh-hunting days, most boats were handmade wooden bateaux, built wider than a Louisiana pirogue since our much-higher tides and more-open marshes required a more seaworthy craft. Two types populated the marshes before World War II: oyster bateaux, which were 16-foot-long, 6-foot-wide, open pine boats with pointed bows; and rowing bateaux that measured about 14 feet long, narrower and lighter and often made from cypress. Oyster bateaux were skulled with a single oar; rowing bateaux were fitted with a pair of oars and were typically the ones used for marsh hen hunts around the high tides.

In the days before most boats carried outboards, hunters had to play the tides, riding the rising water on their trip away from the hill and returning on the falling tide, using the ebb and flood to their advantage.

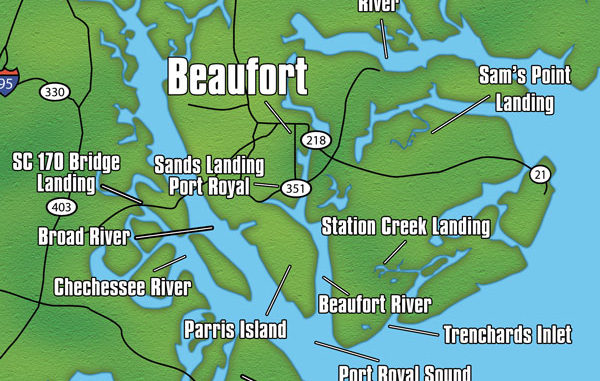

Ralph Davis, who was raised on the plantations of Wadmalaw Island just south of Charleston, spent most of his adult life plying the waters around Saint Helena Island, near Beaufort, and he knows them intimately. Being raised as one of a handful of whites among the black plantation populations, Davis speaks the native Gullah language fluently and learned the local hunting and gathering traditions related to the barrier and sea islands. A favorite in the fall is shooting marsh hens.

Davis’s approach is typified by consecutive November hunts, the first by himself and the second with a friend, Jack Schaaf. The approach is slightly different when going alone, but in both cases the hunter enters the marsh as the tide approaches its flood stage, arriving at the landing about 1½ hours before the peak high tide.

On the second hunt, the tide was predicted at 8.8 feet high at 8:57a.m. After quick greetings at the landing and loading of gear, the little wooden bateau motored out toward the oceanfront to meet the rising tide. The idea is to work the water from the more oceanfront areas, where high tide is earlier, back toward the up-creek areas to take full advantage of the high water.

Davis and Schaff, both former fighter pilots, began chasing marsh hens more than 50 years ago and still manage a hunt or so each year with sons, grandsons or friends.

Once near the oceanfront, plenty of rails were visible loafing on the floating wracks of sedge and in sparse clumps of Spartina remaining above water. After loading the shotguns, the next task was to motor slowly into an upwind position and then close to flushing distance with the pole. Davis stuffed three shells into his humpback, 20-gauge Browning, even though he never fired more than once at any flushed bird.

According to bird books, clapper rails range from Cape Cod to the Texas gulf coast, are 14 to 16 inches long and only inhabit coastal salt marshes. Their listed size is misleading, as they have extremely long necks. Their body mass is similar to a bobwhite quail or an American woodcock. Most any coastal salt marsh in the Carolinas and Georgia should hold birds, but in our area they are particularly plentiful.

Marsh hens would rather hide in the grass or swim away from approaching danger than fly, so the object is to pole in on them quietly, otherwise, they will swim away. If you push them toward a small, dense clump of exposed Spartina where they think they can hide, they will often hunker down and wait. When you get within 15 to 20 feet of the hiding birds, they often fly. If not, you move even closer and slap the water to scare them into flight —and even that is sometimes not enough to get them airborne. Even at that range, rails sometimes just swim away, often putting a wrack of unpenetrable floating sedge between you and them and leaving you slapping the water and shouting, “Fly, damn it!”

The little bateau, being designed very narrow abeam to pole easily through the grass, is a bit tippy for someone not fully steady on their feet. At first, Davis tried to stand and shoot but couldn’t keep his balance well enough to hit the birds. Once convinced to shoot from a seated position, a technique that most people use in the wiggly bateau, he started hitting birds.

By the November hunt, most of the Spartina dies back or becomes windblown, and a big tide fully exposes the birds. Except for the poling, the hunting is easy — which isn’t bad. In an next hour or so, Davis shot a limit of 15 rails, with only a few kill shots from the guide, all while being poled into range in the classic manner. He was repeatedly teased that it was likely his first fully legal limit of marsh hens in 50 years.

When working hens solo, you have to do both the poling and the shooting, but clapper rails’ hesitancy to fly allows a solo hunter to get real close and thus have time to put down the pole, pick up the gun and fire before they get out of range. Often, the challenge is to shoot them before they land again rather than fly out of range.

Hunts typically only last two to three hours, while the water is high enough to pole through easily, with the bigger tides giving you some extra time. On a good day, a limit can be collected in an hour, but some days are tough because of the wind or tide. Even on a predicted big tide, a west wind can keep the water from fully rising and ruin your hunt. Other times, strong east winds blow in tons more water than predicted, and some days the wind is so strong it is scary in a tiny boat.

Marsh hens are easy shooting for sure, on good days perfect for introducing youngsters to shooting at flushing birds. It is even more satisfying when done the old fashioned way. Sliding over a flooded coastal marsh with a friend on the pole and you standing in the bow, the rising sun of a cool autumn morning at your back, an old shotgun in hand and marsh hens ahead transports you back to when life was simpler and maybe better.

Be the first to comment