The Little River on the ‘Peaceful Side of the Smokies’ is a top-100 trout stream in America.

Guide Gene Shuler approached the East Prong of the Little River’s first pool below the Chimneys campground on his hands and knees and from the side to avoid being seen by trout chasing cream midges to the surface.

The sky was totally free of clouds, the sun beginning to warm the surface water of this well-known trout stream. Dozens of insects swarmed above the pool, but only a few larger brown bugs were flying above the stream’s surface.

Shuler didn’t have a fly small enough to match the tiny midges, so he tied on a No. 14 March Brown and flipped it with his 9-foot, 5-inch rod to the foot of the shallow riffle at the head of the pool. As the dry fly drifted slowly downstream, he began stripping in line in short jerks, trying to imitate a swimming insect.

With his polarizing sun glasses, Shuler saw a decent-size trout cautiously approach the fly in the gin-clear water, bump it, then swim away.

Two additional casts to the same area produced similar results — bumps but no strikes.

This type of inspection and rejection by trout was foreign to Shuler. He knew something was wrong, but he didn’t know the source of the trout’s reluctance to take his offerings. He didn’t believe the trout had seen him approach the pool, and he has taken many trout at other streams with the March Brown.

“What’s going on?” he said.

Shuler has hooked and netted many trout at other heavily fished streams, so this fishing was becoming frustrating.

Perhaps the trout in this pool had been spooked by children wading in the shallow water above the riffle or maybe they’d tossed stones into the water. A family of four, including two small children, left the stream as Shuler approached the pool.

At any rate, he thought he’d better change locations, so he carefully waded out into the stream, keeping a low profile as he approached the next run above the riffle.

Shuler cast the March Brown to the head of the swift run and stripped line as rapidly as possible to keep up with the movement of the floating fly. It was almost back to him on the riffle when he had a savage strike.

He set the hook (he thought) with the snap of his wrist, and the fish instantly put a good bend in his rod as it struggled to escape. Seconds later, a 12- to 13-inch rainbow parted company with the hook. He had a brief flashing side view of the fish as it swam away.

An hour earlier, when he first started fishing this Smoky Mountains National Park stream, Shuler had spent about 30 minutes casting dry and wet flies unsuccessfully to trout in the long, deep pool below The Sinks, which is located several miles downstream.

Many large brown trout reportedly have been taken from that pool, but Shuler

didn’t get a strike, only a few bumps.

He didn’t reach The Sinks until around 10 a.m., and since it was almost noon, it was nearing lunchtime, and Shuler needed a break.

At his Hummer parked at the campground parking lot, he shed his wading shoes, waders and fishing vest.

After wolfing down a cheeseburger, fries and a drink during lunch bought at nearby Townsend, Shuler said he thought he’d be able to solve the dilemma by day’s end.

His next stop was at the Fighting Creek Gap area, just above the last Tennessee Rt. 73 bridge to span the river before the Elkmont turnoff.

There is considerably more incline to the river bed in this section, and many of the runs and pools are smaller and swifter than similar downstream waters.

Approaching a shaded pool that swirled against a high rocky cliff, Shuler said Little Sally and sulfur flies were leaving the water.

He deftly cast a No. 14 Little Sally dry fly to the water between the cliff and the riffle and almost hooked an aggressive, 12-inch rainbow, but the trout didn’t have the fly entirely in its mouth.

After two futile casts near the cliff, Shuler switched to a No. 12 Mr. Rapidan dry fly. His cast to the center of the pool attracted 8- and 10-inch trout. One of them bumped the yellow-black-gray fly during Shuler’s retrieve, then both swam away. But his retrieve again had been through relatively slow-moving water.

At the head of the pool, water rushed through the rocks in a steeper riffle.

Shuler’s next cast dropped the wet fly onto the fast water. It barely touched the surface before a trout grabbed it, ripping off line after the angler set the hook.

After a brief fight, Shuler led the brightly colored 9-inch brown trout into his landing net. As he reached into the net to hold it up to see the fish more clearly, it was evident the hook wasn’t in its mouth.

“This has been the most frustrating experiences of my fishing career,” said Shuler, a top-ranked professional fly-caster. as he returned the fish to the stream.

“When those trout had time to notice my fly didn’t wiggle and try to escape when they bumped it, they knew it was a fake and refused to bite it,” he said. “The only chance I had of hooking one was to drop the fly into water that was moving too fast for them to carefully examine it.

“In the two fast-water areas where I hooked trout, the fish had to strike immediately or pass up a potential morsel of food. Real emerging insects have a soft body, so the hard body of my flies didn’t fool them a bit.”

Shuler and Richard Bauer, another Great Smoky’s trout guide, have made notice of their successes using Creme Lure’s soft-plastic caddis-fly nymphs.

So Shuler decided to see if the local tackle shops stocked these nymphs.

Walter Babb also had trouble trying to hook fish at the Little River during July and September. He, too, had many bumps but landed only one legal-sized trout each trip.

Babb, a well-known and respected local fly tier and angler, has spent 30 years fishing area trout streams. For health reasons, he had to give up guiding but still teaches fly casting.

“Expert fly anglers from other areas of the country have been skunked at the Little River,” Babb said, “including two experts from Montana and one from Pennsylvania.

“These are wild trout, and they’re much warier than hatchery-raised fish.”

Shuler agreed with Babb’s assessment of Little River trout.

“This is the most difficult trout stream I’ve ever fished,” he said “and I’ve fished many streams in several parts of the country.”

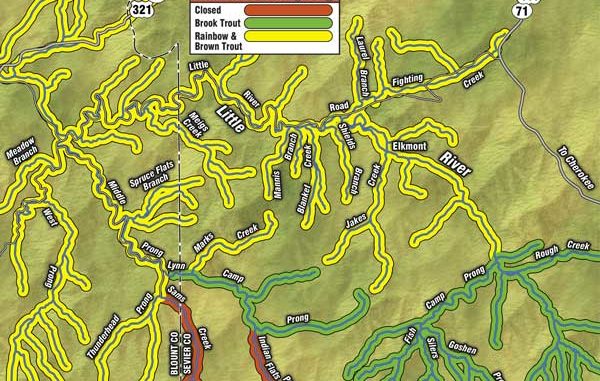

The three forks or prongs of the Little River drain 243,200 acres of moderate to steeply sloped forest that extends from Mount Collins at the northeast to Thunderhead Mountain at the southwest in the Tennessee portion of the Great Smoky Mountain National Park.

Some 1,625 miles of streams are included in the drainage, according to Cathy Rhodes, executive director of the Little River Watershed Association.

Before the first white men arrived, these streams contained three game fish — the southeastern subspecies of the Eastern brook trout lived in the higher, colder streams, while smallmouth bass and rock bass generally lived at lower elevations of the main streams and below The Sinks at the East Prong.

After the more accessible areas were heavily lumbered, brook trout retreated to the highest elevation waters.

In 1934 western rainbow trout and northern species of brook trout were introduced to the lower waters and restocked annually until 1974 in heavily fished sections and those segments adjacent to campgrounds.

German browns were released by individuals and well-meaning fishing organizations.

Because these releases threatened the existence of brook trout, GSMNP officials closed all streams to brook trout fishing in 1975 and they remained closed until 2002, when an experimental season was undertaken at 16 study streams in North Carolina and Tennessee.

Two Little River tributaries were included in that study; Fish Camp Prong was fished, while Silers Creek was unfished but studied.

Data from the study showed legal fishing had caused no significant declines in adult brook trout density, size, young-of-the-year density or in the total number of legal-size brook trout in seven of the eight fished streams during the study. A significant increase in size was observed in adult fish at Hazel Creek in North Carolina.

The Park Service hasn’t stocked rainbow or brown trout since 1974 because population studies revealed most of the streams already contained all of the trout the food supply could support. Many streams contained 2,000-4,000 trout per mile, many only 4 to 8 inches in length.

Also, the primary mandate of all national parks is to protect and preserve the natural and cultural resources within for the enjoyment of present and future generations.

“Someone finally realized in 1975 that we were stocking non-native species in the national park,” said Matt Kulp, Park fishery biologist. “That was in direct contrast to our mandate,”

Studies have revealed Little River rainbows are the fastest-growing trout species, but browns live longer and frequently grow larger.

While it’s uncommon to catch a brown longer than 20 inches, Lacy Schults caught a 32-inch, 12-pound brown trout at the Middle Prong during 1980. That catch is the largest recorded trout taken from Little River waters.

Kulp said it’s unusual to catch a brookie longer than 9 inches.

Aquatic insects make up the bulk of trout food, but the larger browns and rainbows also feed on crayfish, minnows and very small trout.

“There are a variety of aquatic insects available, but the big three are mayflies, stoneflies and caddis flies,” Kulp said.

Wading can be difficult at many stretches of these streams because of thick brush overhanging the higher tributaries and swift currents and sharp drop offs in the lower East Prong.

The distance between many popular drop-off and pick-up points can be quite long, if anglers fish the entire stretch. The distance from the Cades Cove turnoff to the Elkmont turnoff is approximately 12 miles, and The Sinks is the halfway point. At the Middle Prong, the distance from the Cades Cove turnoff to where the Thunderhead Prong and Sam’s Creek join is about 7.2 miles.

Trout fishing is legal each day of the year from a half hour before official dawn to a half hour after official dusk, except two streams, Sam’s Creek and Indian Flats Prong, are closed to fishing. They’ll reopen after fish populations recover from restoration, said Kulp.

A valid North Carolina or Tennessee fishing license is required to fish park waters in either state, but a state trout stamp isn’t needed.

Only single-hook artificial lures are legal. However, the use of a dry fly as a strike indicator above a nymph is permitted.

There’s a combined five-fish creel and possession limit for all trout species and small mouth bass. All kept trout and smallmouth must be 7 inches or larger. Twenty rock bass of any size may also be kept.

“Little River is one of the premier streams in the park and the country,” said Kulp, when asked how he would rate this stream in comparison with other park trout streams.

In his book, “Angler’s Companion to Trout Fishing in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park,” author Ian Rutter said “Little River is easily the most popular stream in the park and one of the prettiest trout streams in this part of the country. The river’s winding nature produces many large pools and long runs. A fisherman will have to look far and wide to find a wild Appalachian trout stream that has as much to offer. In fact, the stream was counted among Trout Unlimited’s top-100 trout streams in America.”

Heavy kayak and rubber raft traffic during the summer months and above-average fishing pressure much of the year cause trout to spook easily.

The Little River has a unique mix of roadside and pack-in angling. From the park boundary near Townsend to the campground at Elkmont, many miles of roadside fishing are available, but pullout parking spaces aren’t always conveniently located near desirable pools and runs, so considerable walking may be required.

From Elkmont at the East Prong and from end of the road parking spots at the Middle and West prongs, there’s more than enough hike-in and camp fishing to satisfy almost any angler. Especially at the more remote brook trout streams, fishers are unlikely to have much company, especially during week days.

A free backcountry permit is required to spend the night in the Park’s backcountry. Day hikers aren’t required to register or obtain permits.

The Sugarlands and Cades Cove visitor centers and the Elkmont ranger station have free brochures to pass out that show the location of open and closed streams and developed campgrounds. The pamphlet also includes color illustrations of the park’s five gamefish species and fishing regulations are spelled out.

Summer visitors may avoid the crowds by traveling before 10 a.m or after 4 p.m.

To request a copy of their Smokies Trip Planner or for up-to-date weather and road information, call (865) 436-1200 or visit www.nps.gov/grsm.

If you’ve never visited the Little River, the beautiful scenery is enough to justify the trip. If you also fish, you’ll likely enjoy the challenge of trying to outsmart some wary fish but may be rewarded with a nice catch of native trout, if you’re a skillful or lucky angler.

If you aren’t an experienced fly fisher, chances of landing a large East Prong trout will increase greatly with the aid of a good guide for at least a day.

Be the first to comment