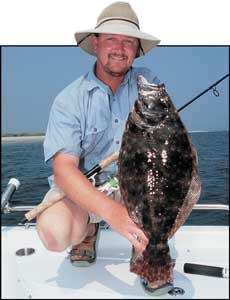

Anglers who love to fish for doormat-size flatfish need persistence to score big at crowded Carolina Beach.

Carolina Beach has earned a reputation for producing some of the nicest catches of big flounder in the state of North Carolina and perhaps the world. But the waters of the Carolina Beach flounder zone, which extend from the mouth of the Cape Fear River northward to Carolina Beach Inlet and out into the Atlantic Ocean a few miles toward Wrightsville Beach, are becoming more crowded by the minute. The area is one of the fastest-developing human habitats in the country. No longer the sleepy little community of three decades past, the building boom is fueling a huge surge among flatfish anglers.

While the competition can be fierce, there’s still no better place to catch a big flounder. Charter captains such as Walter Bateman have learned to join the crowd when seeking doormat-size flounder.

“It’s no secret that Carolina Beach Inlet is the place to go for big flounder,” said Bateman, who operates Coastal Carolina Guide Service. “You can pick your poison and anchor your boat or drift with the current. You just have to know how to contend with other traffic going in and out of that area.

“Always point your boat out toward the channel because there are going to be some big wakes that could swamp a small boat if they come over the stern. Wind and current can magnify the size of the boat wakes, so you have to be aware of what’s going on around you.

“It’s a navigation inlet, so you have to be patient, and the fishing is crowded. Other people will fish right beside you, but if you can tough it out, you’re going to catch some fish.”

Bateman puts flounder in his boat during every tide stage at Carolina Beach Inlet. However, he prefers to fish during rising tidal periods.

“I have a 45-minute rule for most other places when I’m fishing for flounder,” he said. “But Carolina Beach is one of the few places I won’t leave because I know there are big fish there. If you’re anchored up at a good spot along ‘The Hole,’ you don’t want to move or somebody will move into your place. You have to have the confidence to know you’re going to get a bite.”

The “Hole” goes by many names. At the south end of Masonboro Island (the north side of the inlet) where the channel joins the ICW, vehicles were once parked after being ferried across by surf fisherman. That practice ended three decades ago when the state purchased Masonboro Island and converted it into an estuarine reserve. Now a few of the old rusted-out automobile frames remain visible during low tides, giving the “Hole” its former name of the “Parking Lot” or the “Old-Car Hole.”

More recently, erosion-felled trees toppled into the water, and anglers re-named the hot spot “The Tree” and “The Tree Hole.”

“The Hole has a ledge that drops from 8 feet to 30 feet,” Bateman said. “The current is really strong, so you have to use an anchor bigger than you boat usually calls for. Sometimes you get a good hang, and sometimes it takes several tries, so you have to watch where other boats are anchored in front of you so you don’t snag their lines if your anchor doesn’t catch. Sometimes it catches the ledge and you lose the anchor.”

Anglers must also be prepared to lose some rigs. The ledge is rocky and shell-covered; it eats hooks, lines and sinkers.

“The ledge is the reason the flounder are there,” Bateman said. “You’re going to lose some rigs, so you’d better take along some extra tackle. If you don’t get hung up, you aren’t fishing in the right place.”

Hang-ups occur whether an angler is drifting or anchored. The swift current sweeps by the ledge, taking the tackle into the hard structure.

“I use a 6-foot, 6-inch St. Croix medium-action spinning rod with a Daiwa Capricorn 3000 series reel filled with 30-pound (Spectra) PowerPro braid (line),” Bateman said.

“I use a ½-ounce egg sinker most of the time, but I’ll go up to a 1 ½-ounce barrel sinker if the current is strong. You have to keep the bait near the bottom where a flounder lives, so I use a fairly short leader. I use 12 to 18 inches of 20-pound monofilament tied to the line with a swivel and the sinker slides above the swivel.

“Some anglers add floats to keep their baits off the snags along the ledge or at Snow’s Cut and some add plastic beads. I tie on a No. 4 wide-bend hook. It’ll hold a big flounder, but it’s small enough to straighten out with the 20-pound leader most of the time if you get hung. If not, the leader will break before the braided line, and you get to keep your sinker and swivel.”

Bateman has a 12-gallon and a 15-gallon live well in his boat. He fills them as full as he thinks they can get with bait before he goes fishing.

“I use live bait — mullet, menhaden, mud minnows — whatever I can catch with a cast net,” he said. “You’re going to catch speckled trout, gray trout, bluefish, sharks, sea bass, ribbonfish, Spanish (mackerel) and some rays. They’ll eat your bait supply in a hurry.

“The worst thing is hooking a big ray. You don’t want to lose a world-record flounder, but after a few minutes you can tell if you’ve hooked a ray because they don’t give up. It’s better to break him off than waste an hour trying to catch him by pulling the anchor and following him.”

Bateman sometimes fishes at Snow’s Cut. It has a reputation for big flounder but can be difficult to fish.

“Snow’s Cut is really snaggy and a great place to lose an anchor,” Batman said. “Drifting is effective, but you can count on losing some rigs. Drifting during the slacker tides helps. Rising tide and falling tide can created different drift directions along parts of the bank, and the tide and wind can be doing different things to the boat at the same time so you never make the same drift twice. Wind and current can create eddies that can spin your lines together, so you have to keep them tight.”

Bateman keeps the motor running and kicks it in and out of gear to steer the boat. He fishes near the bank along the channel edge, but keeps out of the main channel. Boat traffic sticks to the main channel, and there aren’t as many flounder in the deeper water.

“Sometimes fishermen use very little weight or a cork on the flounder rigs to keep the hooks off bottom,” he said. “I use really light barrel sinkers to keep from hanging up in the rocks.

“A No. 4 wide-bend hook catches big fish and little fish, but I can straighten it out with a good pull.”

Once a fish is hooked, Bateman has his clients keep the rod tip up, never pointing it toward the fish.

“If he gets a straight pull, he can pull free,” he said. “I prefer leaving a bend in the rod and some line out. Otherwise, the rod’s in the way when you try to get the net around the fish’s head, and you’ll be fumbling around. You can’t net a flounder from the tail.”

Bateman uses a 34-inch walleye net with a telescoping handle big enough to land a man. He stores it until getting ready to fish. Anglers sometimes question the need for the large net, but most don’t because they’ve come for the trophy flatfish.

“I lived around Carolina Beach all my life until a couple of years ago, and I’ve been guiding since 1998 and I just turned 37,” Bateman said. “I moved to Sneads Ferry for the drum and trout fishing, and (that area has) some flounder. But if anyone wants a big flounder, I always return to Carolina Beach because that’s where they live. If you want to win a tournament, you go there.”

But make no mistake; flounder fishing can be b-o-r-i-n-g. Anglers might fish all day for a few fish. During a typical day, Bateman’s clients catch eight to 10 fish between 1 and 3 pounds, perhaps with a 5-pounder in the mix. Sometimes they might catch just one fish, but that single flatfish always seems to be a big one that may weigh at least 8 pounds.

“I’d rather catch one big fish than lots of smaller ones,” Bateman said. “But different people might rather catch the big numbers of fish.”

For inexperienced anglers, detecting a flounder strike and hooking a fish can be difficult. Those familiar with setting the hook at any sensation of a fish taking the bait will have poor luck.

“After a couple of times, most fishermen can tell a flounder strike from a speckled trout strike,” Bateman said. “I tell them to wait for 30 to 60 seconds before setting the hook on a flounder. You can’t wait too long when a flounder is eating the bait. When you set the hook, set it hard.”

Bateman fishes from a Sea Pro boat. When a couple of his regular customer liked his craft so much they bought their own models, he went along for the maiden voyage to Carolina Beach Inlet.

“We always have good luck when we fish with Walter,” Mike Maguth said. “I caught a nice gray trout, and Ralph caught a 4-pound flounder.”

“Walter has taught us a lot about flounder fishing,” Ralph Edgar said. “He helped us out with the shakedown cruise. We’ve been fishing with him for several years, and I think we’re ready to try it on our own. This inlet has some really good fishing.”

Capt. Barry Phillips of Fish Stalker Guide Service at Southport fishes the creeks and ICW near the Cape Fear River mouth. He uses the same baits and tactics as Bateman.

“I fish at Fort Caswell a lot,” he said. “The hard structure areas along the shoreline hold some nice flounder. I also fish the boat docks in Dutchman Creek and the sea walls at the Bald Head Island Marina entrance channel.”

Phillips anchors his boat, sometimes using two anchors to keep the boat from swaying in the current and wind. He likes the boat stationary so he can feel the sinker contacting the bottom.

“If you can’t feel the fish bite, you can’t catch him,” he said. “Once I feel him pick up the bait, I usually wait until he moves off with it before setting the hook. That way I know he has it well back inside his mouth or has swallowed it.

“More flounder are missed by setting the hook too soon than for any other reason. The second reason fish are lost is rushing them to the boat. If he’s not tired out, and you get his head out of the water before you net him, he can throw the hook.”

Phillips spends a lot of time obtaining baitfish. He likes to use finger-sized mullet and it takes a lot of time to fill his boat’s live well.

“I look along the Waterway edges and at the bars in the creeks,” he said. “(Baitfish) are usually easier to find early in the day. The creeks get shallow at low tide, so you have to know where you’re going. You can get stuck on a bar if you aren’t careful and get too involved in throwing the net.”

Ned Connelly catches flounder from Wrightsville Beach to Southport. Last summer, he caught his biggest flatfish, an 8.4-pound summer flounder that came from the hard-bottom area between Carolina and Wrightsville beaches.

“There are lots of flounder out there at John’s Rock,” he said. “But it can be tough fishing. You get hung up and lose a lot of rigs, and other fish eat your flounder baits. A school of bluefish can burn through 100 baits in a few minutes.

“If you’re fishing (with) two people, you’ll need about 50 baits an hour.

“The last thing you want to do is head home when the fish are still biting because you were too lazy to catch enough bait.”

Be the first to comment