If sheepshead consistently frustrate you, this winter approach may change your attitude about saltwater’s most notorious bait-stealer.

Driving to the boat ramp in fog as thick as she-crab soup, I thought I might be an idiot.

It was January and the air at the ramp’s parking lot was damp and clammy. Sitting in a deer stand or duck blind in these sorts of conditions is no problem, but the idea of running nearly 20 miles offshore gave me the chills.My fishing partner was just finishing launching his boat when I made it down to the pier.

“The fog is kinda thick,” said Capt. O.C. Polk, his image materializing through the fog like bad special effects in a low-budget horror movie. “That’s alright. The forecast is promising, and it should end up being a beautiful day.”

Those who know Polk’s experience know better than to doubt him but as the visibly heavy mist waffled between us I couldn’t help but think the start of a beautiful day was my head back home on the warm pillow.

We stowed the rest of the equipment in the boat, the depth-finder was turned on and the GPS was waking up and locking itself to several satellites orbiting overhead.

I have idled out of Shem Creek in Mount Pleasant many, many times before a fishing trip but this morning the creek stood in stark contrast to those warmer weather trips. The sounds of purring diesels from the shrimp-boat fleet and sportsfishers that line the creek were missing. My hands were not busy lathering on sunscreen either. I was pulling my fleece up around my neck and digging in my backpack for a winter stocking cap.

Hanging a left out of the creek, visibility was improving. By the time we had reached the Charleston jetties, a Carolina blue sky was hanging over us. Looking back over my shoulder at the fog bank lifting over Charleston was beautiful.

A calm Atlantic Ocean was laid out in front of the boat’s bow. A long-time head boat captain, Polk’s ability to find fish is common knowledge in the Charleston fishing community. After plying local waters for four decades, he knows the ocean’s bottom and what it holds better than someone knows their house in the dark. We headed southeast towards an uncharted shipwreck.

After a 20-minute ride, the GPS alarm sounded. I unzipped my hunting coat while Capt. Polk drew circles on the ocean’s surface looking for the wreck. The view of S.C.’s offshore waters on a depth-finder is as flat lined as Jimmy Hoffa’s EKG printout. If you find a blip on the depth-finder offshore, you should fish that spot.

“Get the anchor ready,” Polk said as the depth-finder showed the spikes of the wreck. He gauged the currents and wind and ordered the anchor dropped. We were in position.

Fiddler crabs, a sheepshead delicacy, were squirming around in a five-gallon bucket like a disturbed fire-ant mound. Polk grabbed one and threaded the hook up through the crab’s abdomen so the point was barely poking through the crab’s top shell.

“Drop it down, and let it hit the bottom,” he said. “It’s just like any other bottom fishing. You’ll feel the fish tap, and then set the hook.”

I watched my fiddler crab descend in the clear water, leaving a trail of bubbles in the process. Honing my saltwater teeth on redfish and trout, I wasn’t a sheepshead bite veteran. Knowing about a sheepshead’s reputation for stealing bait, I inquired Polk what to expect.

“Sheepshead are really hungry offshore in the winter,” he said. “People say to me that they can’t catch any sheepshead, and I tell them all they have to do is come offshore during the winter.”

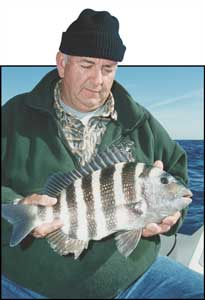

He was right. My bait had hit the bottom, and within 15 seconds a fish bit. No need to set the hook. My rod was already bowing. After a sturdy fight, the tell-tale zebra pattern of a stud sheepshead was appearing in the water column.

Throughout the morning, we caught several more sheepshead, including a back-alley brawler weighing about 8 pounds. The grizzled 12-pound brute remained elusive, but in addition to the sheepshead we also landed a few above-average black sea bass.

Anglers may encounter a lingcod too, a rare snowbird to Lowcountry waters but common farther north. Polk landed one during our trip.

“The sheepshead are on the reefs all year,” Polk said. “You can fish for them out here during the warmer months but other non-target fish will harass your bait.”

What makes winter offshore sheepshead fishing so attractive is the fish devour baits rather than nibbling them off your hook and the large number of fish.

Winter weather has them hungry. When inshore anglers come across sheepshead during the summer there is a plethora of food plus energy demands are much lower. Additionally, sheepshead aren’t ganged up as much during the summer as they are during the colder months.

“You might still find some holdover sheepshead inshore during the winter,” Polk said. “If you’re fishing around some docks for winter trout, you might get a sheepshead. However, most of the inshore population moves to offshore structure as the water cools. When that population has moved out there, it can be a load of fish.”

The affinity of sheepshead to structure is tied to their feeding habits. Check out the dental hardware of a sheepshead and notice that it has blunt, chisel-like teeth positioned well forward in its mouth. The arrangement and style allows the fish to scrape marine life, such as barnacles, off of hard structures.

Starting right at hard structures just off of the beach, anglers will find sheepshead as far out as water 100-feet deep. But there’s no need, especially if you are a small-boat angler, to search that far offshore. Many fish can be landed in 20 to 50 feet of water.

“You can find sheepshead at the Charleston jetty,” Polk said. “I like to fish farther offshore because the pressure is less and you have a greater chance of landing larger fish.”

That said, the state-record sheepshead, 15 pounds 12 ounces, was landed by Doug Hoover near the Charleston jetties. The fish also are located at the jetties guarding Winyah Bay, Murrells Inlet and Little River.

The best places for anglers unfamiliar with offshore waters are the many artificial reefs dotting the coast. A list is available at the SCDNR Web site. They are also located at many commercial maps along with other notable bottom features that may support sheepshead (see sidebar).

If you can fish the pieces of structure on the fringe of the reef, your chances of a trophy fish are increased.

“Fiddler crabs are a year-round favorite of sheepshead,” Polk said. “You can dig them yourself, but many tackle shops carry them during the winter. Live shrimp are usually available in tackle shops as well, but they’re pricey for this sort of fishing.”

As with any bottom-fishing, plan to lose a few rigs. One of the best, most inexpensive and easiest rigs is a Carolina rig. Polk rigged our rods with a 2-ounce egg sinker above a barrel swivel. Hook sizes may range from a No. 1/0 to 3/0 with a 12- to 24-inch 20-pound monofilament leader. We used medium-action spinning rods spooled with 15-pound-test line. Berkley Power Pro line is becoming attractive to bottom fishermen because of its lack of stretch.

You can employ a two-hook bottom rig that features a bank sinker on the bottom, but the added hardware means additional costs and a greater loss if you get snagged or break off.

The last piece of equipment that is imperative is a landing net. Sheepshead have tough mouths that sometimes lead to a weak hookset. So you don’t want to risk hoisting one over the gunwale. From a safety viewpoint, hypothermia is a threat in the winter and you can reduce your chances of falling overboard by using a net.

If sheepshead have always had the upper hand on you, now is the time to even the score.

Be the first to comment