Hunters understand the need to harvest does, but many are confused about when, why and how many. Two deer managers answer those questions.

Twenty-five years ago, killing a doe deer was not only disapproved of, it likely would get you run off the property you were hunting or kicked out of your club.

Through grassroots efforts by a number of concerned deer hunters, biologists and land managers, the tide of popular opinion turned, and by the mid-1990s, the antlerless deer harvest in South Carolina — as well as the overall deer population — was at an all-time high.

But even with the doe harvest now recognized as a sound management tool, many hunters still have questions about when does should be harvested and how many.

Two biologists who can supply the answers are Charles Ruth and Joe Hamilton.

Ruth is the deer-project leader for the S.C. Department of Natural Resources, and Hamilton, a former state biologist, is founder of the Quality Deer Management Association.

Some hunters still don’t understand that killing does actually benefits the overall deer population — especially when combined with the use of restraint in taking younger bucks. According to Hamilton, that’s an equation for a healthier herd and bigger bucks.

“Having too many does in a local deer population leads to reduced nutrition for the entire herd, including young bucks,” Hamilton said. “Less nutrition means reduced body weights and reduced antler development.”

Ruth agrees.

“The worst scenario is a property or club that aggressively pursues the harvest of bucks only and takes no female deer out of the population,” he said. “My suggestion is that managers should have a plan in place prior to the season for quality deer management, and that plan should include the number of does that should be harvested.”

Regulations guiding the harvest of deer, be they bucks or does, are pretty broad across South Carolina. However, Ruth is quick to point out that hunters should not attempt to harvest a limit of deer on their hunting grounds, just because it’s allowable by law.

“The burden is still on the individual hunter and land manager to act within the framework of the law to manage their own areas,” he said. “While the overall deer population is stable, it’s impossible to regulate appropriate harvest numbers by law only. That’s why each hunter and each land manager is responsible for their own deer herds, within the limits of the law.”

“The responsibility for quality deer management definitely falls on the shoulders of the hunters,” Hamilton said, “but South Carolina hunters have proven they are more than up to that responsibility. Early in the 1990s, South Carolina was one of the first states where antlerless deer harvests exceeded antlered deer harvests. South Carolina hunters were some of the first to take advantage of the doe-harvest programs that offer a lot of flexibility for managing deer.”

South Carolina provides hunters the opportunities to harvest antlerless deer through a variety of programs, including specific doe tags and general either-sex days during the season.

The deer-tag program can be further divided into two programs: the Anterless Deer Quota Program and the Individual Antlerless Deer Tag program.

“The quota program is a property-based system where tags are allotted based on the acreage owned or controlled by the applicant,” Ruth said. “On the other hand, the Individual Tag Program is a hunter-based system where the hunter uses the tag to harvest antlerless deer. The quota program is more popular in the lower part of the state, where land managers control large tracts. The application fee is $50, and tags are issued based on the number … needed for that particular tract. The individual tag program is more popular in the Upstate and more suited to the average hunter who either hunts game management lands or smaller private tracts. Each hunter can apply for either two or four of them at a cost $5 for each tag.”

Unlike the quota program, which requires hunters to tag all antlerless deer regardless of the date of harvest, individual tags allow flexibility for hunters who may be in the woods on days other than designated either-sex days —when tags aren’t required. As an added bonus, the money generated from these tags is specifically ear-marked for deer research.

“It may seem complicated, but the goal is to allow hunters the flexibility to harvest does within a framework that’s healthy for the state’s population and convenient for the hunter,” Ruth said.

Either-sex days are decided upon within the framework of the hunting season, and they allow antlerless harvest on lands other than quota-managed properties. Over the years, either-sex days have gone from one or two per season to a nearly every weekend, and they have been adjusted in recent years to match the capacity of the deer herd.

“Ideally, in the future, I would like to see our deer harvest come in line with some other states where tags are issued for both bucks and does” said Ruth. “This would help tremendously with the management aspect, while hunters would still have the flexibility to harvest both bucks and does as they see fit for their hunting grounds.”

Being able to accurately assess the deer harvest and population trends is a key for Ruth and other deer managers. Biologists believe that before making changes to deer regulations, they should have a foundation in biology; the population dynamics associated with annual hunting mortality cannot be ignored.

In other words, it takes good numbers to support proposed regulation changes or tweaks.

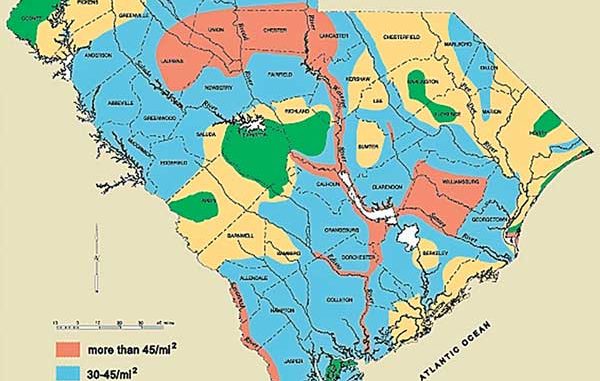

Methods used to document South Carolina’s deer harvest have changed over the years. Historically, harvest figures were developed using mandatory check stations in the 18 Upstate counties (Game Zones 1 and 2) and the reported harvests from properties enrolled in the Antlerless Deer Quota Program (ADQP) in 28 coastal counties (Game Zones 3, 4, 5 and 6). This system yielded an actual count of harvested deer and was, therefore, an absolute minimum harvest figure.

The system’s shortcomings included deterioration of check-station compliance and failure to report harvested deer by ADQP cooperators. Also, since the acreage enrolled in the ADQP accounts for only 50 percent of the deer harvest in those four game zones, past harvest figures did not account for deer harvests on the nearly four million acres of non-quota lands, because there was no legal requirement to report harvested deer in those areas. Therefore, it is suspected that historic deer harvest figures only accounted for about one-half of the state’s annual deer harvest.

The SCDNR decided that an annual hunter survey would be a better analytical tool. The Annual Deer Hunter Survey represents a random mailing involving a database constructed by randomly selecting 25,000 hunters who bought big-game permits.

By applying the statistical method to the results received from surveyed hunters, Ruth and other SCDNR staffers can construct a remarkably accurate assessment of what was killed, where and when, in any particular season.

SCDNR has available for hunters a wealth of information, including harvest data, antler records and other statistics on its website, www.dnr.sc.gov/wildlife/deer/index.html.

Be the first to comment