Here are some tips to draw a full house on Lowcountry waterfowl.

Duck hunters in the Lowcountry’s ACE Basin either have connections with a plantation owner who plants food plots and possibly buys raised mallards, or they are rugged individualists with masochistic tendencies.

That’s an exaggeration, of course, but in the expansive waters of the Ashepoo-Combahee-Edisto Basin, ducks are scarce most of the time.

That’s no surprise to Dean Harrigal, the waterfowl program coordiNator for the S.C. Department of Natural Resources and chief biologist for Bear Island and Donnelley Wildlife Management Areas.

“There just isn’t much food in the tidal marshes for ducks to eat,” Harrigal said. “On the other hand, private plantations and some WMAs go to great lengths to attract and hold wild ducks.”

Yes, there are actually plenty of ducks in the ACE Basin, but the average Joe, who doesn’t have connections, needs to work pretty hard to find them or he has to get lucky.

Jay Lovell and other members of the South Carolina Waterfowl Association are among those average Joes who ply legally accessible areas and make the most of what is there. Lovell did not grow up hunting ducks, only coming to the sport eight to 10 years ago when the contractor who built his home got him started. But like many who come later to the sport, he has been bitten by the bug in a big way.

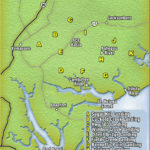

Lovell and his friend, John Hobrook, do plenty of hunting in the ACE Basin, generally hunting in the tidal zone, though most of the time staying beyond the brackish portions of the tidal rivers, in freshwater, using the higher portions of the tide to access old rice-growing areas. Tides come into play mostly as a limiting factor; when the water is too low, hunters can’t get their boats into the abandoned rice plantations and flooded marsh where it’s legal to enter.

What impresses a newcomer to these coastal waters is the massive amount of huntable wetlands and the birdiness of the area, even when you consider that major portions are off-limits as privately owned plantations or protected areas. When navigable water allows easy access, one marvels at the number of places to hide on edges of tidal ponds that look very ducky. They are good spots for sure, but there are not many ducks there. How could there not be ducks all over this place?

“Most of the ducks are attracted to the plantations and the managed wetlands where they plant attractant crops and then flood the fields for the season,” he said.

In preparing for its many public hunts that are controlled by annual drawings, SCDNR also pulls ducks from public areas onto its managed lands. For the public hunter, most really successful hunts accidentally coincide with hunts on adjacent managed lands when hunting pressure pushes birds away. Other times, shooting a few ducks is considered a pretty good outing. As the old saying goes: sometimes it’s better to be lucky than good.

With water depths ranging from mud to 10 feet during different stages of the tide — plus strong currents in the rivers proper — Lovell uses heavy weights and longer lines on his decoys. He doesn’t have to pay out much line in the marshes, but in the rivers, with their stronger current, he’ll unwind most of it.

When setting up in abandoned rice fields, he deploys a sizable spread of decoys that may include bluebills, some redheads, a few mallards, some black ducks and a few pintails — mostly as confidence decoys. He uses whirling-wing decoys in the early season but feels that later on, after the ducks become familiar with them, motion decoys scare ducks away.

When hunting early-season teal, Lovell uses lots of decoys, usually between 18 and 24, with no particular formation except he wants the ducks to approach the spread into the wind and he leaves an open landing zone somewhere. When shooting on rivers, he uses fewer decoys, often including wood ducks in the spread.

Lovell and Holbrook always stay in their boat because of the pluff mud and alligators. Boat blinds, if not a necessity, are certainly a big advantage when the high marsh grasses get beaten down as the season progresses. Lovell covers his 13-foot Boston Whaler with an adapted boat-blind frame and woven marsh grass that he buys for about $50 a box and to which he adds some spray-paint splotches for contrast. Waders are generally unnecessary since hunter don’t leave the boat.

Lovell and Holbrook recommend a few additional accessories that make a hunt more comfortable and safer. Buy and use a strong spotlight to find your way in the twisting mazes of creeks and to signal other hunters of your location. Also invest in a Thermacell insect repellant device because the mosquitoes will carry you away in the early season. DEET repellant works well, but not nearly as well as these little devices.

The action in the November and December seasons is mostly on green-wing teal, with occasional gadwall, widgeon, mottled, pintail and some mallards if the plantations are shooting. There are plenty of buffleheads along the coast, but few people target them.

Lots of hunters frequent the ACE Basin for ducks, and some are experienced, some are novices. Many of the good ones are successful. Be courteous out there, don’t blow your calls excessively and don’t sky bust birds working toward another hunter’s spread. Duck hunting traditions are alive and well in the ACE Basin, even if the hunting is challenging.

Be the first to comment