Besides providing N.C.’s only legal gambling, the Cherokees attract scores of anglers looking for guaranteed creels of rainbows and brown – including some monsters.

Bright sunshine broke through a thin layer of fog lifting off the Oconaluftee River deep in the heart of the Smoky Mountains of western North Carolina, as anglers started taking their places along the pristine stream for opening day of trout fishing at the Cherokee Indian Reservation.It was too pretty a day to ruin with a fall, so David Shehan, 60, and his nephew, Stephen Shehan, 36, both of Greenville, S. C., took their time as they carefully worked their way down the steep muddy bank to the river.

Both were wearing hip boots pulled up as high as the straps allowed to avoid stepping in over the tops in the swift, clear stream.

The water just off shore didn’t look deep, but in fact the two anglers nearly waded above their boot tops as they walked through a narrow channel to a group of large semi-flat rocks some 15 feet in the stream.

They were full from having eaten too much breakfast at the restaurant next to their motel, which added to their unsteadiness as they climbed upon rocks yards apart and sat down.

Should they use salmon eggs, in-line spinners or small spoons to entice some hits from trout?

The older Shehan tied a No. 1 Mepps Aglia with a treble hook to the end of his 6-pound-test monofilament line, and tossed the small spinner just upstream from a large boulder that split a run near the far shore.

He let the spinner sink almost to the bottom before he closed the bail of his open-faced spinning reel and turned the handle once before something almost jerked the rod out of his right hand.

Instantly, he set the tiny hooks in the upper jaw of a large trout that made Shehan’s rod arch sharply as it raced around the long pool. David had preset the drag to a light tension, so it took several minutes before he finally netted a tired rainbow that measured more than 16 inches in length.

“Nice going, uncle,” the younger Shehan said. “Now it’s my turn.”

While his uncle was fighting his first fish, his nephew decided to try salmon eggs. He tied a Size 8 treble hook to his line before crimping on a small split shot about a foot above the hook. An enlarged salmon egg was pierced by each of the three points of the hook, then he cast to the head of a deep run about 30 feet upstream.

Stephen Shehan delayed closing the bail of his reel only a few seconds, but when he did, he knew a fish had swallowed the egg. A trout put a hard, steady pull on the light line as it tried to swim upstream.

This fish wasn’t quite as large as David’s, but it was a scrappy, colorful 14-inch ’bow.

For the next two hours, the Shehans continued to fish this section of the river, using almost every lure they carried, just to see which ones were most attractive to the trout.

The bad news was the experiment failed; the good news was it didn’t matter. Each lure or bait caught one or more fish. By the time they stopped for lunch, they’d taken a total of 19 trout, with the uncle winning the contest by one fish. The happy fishermen removed their boots, stowed their gear in their car and called it quits.

“We’ve been coming up here for opening day fishing since 1977,” Stephen Shehan said, “and we’ve missed only one opener in 28 years.”

The previous afternoon David Ensley, manager of game and fish for the tribe, gave an update regarding the Cherokees’ pay-to-fish program is progressing.

“Each year, we’re seeing an increase in the number of fishing licenses sold,” he said. “Last year we had about 4,000 anglers here for opening day, and based on advance license sales, it looks like we may top 5,000 for opening day this year.

“We have a high rate of repeat customers, and many of them bring friends when they return. We’re obviously pleased for the need to increase our stockings because more guests are catching more fish.”

During the week before opening day, Ensley and his 9-man crew of technicians and law enforcement officers stocked 13,000 pounds of rainbow and brook trout in the 33 miles of four streams and three ponds that make up Enterprise Waters, the business name of the Cherokees’ pay-to-fish waters. The tribe stocked 157,500 pounds of trout during 2004.

Enterprise Waters consist of Raven Fork River from its confluence with Straight Fork River downstream to its juncture with the Oconaluftee River; the Oconaluftee from that point downstream to the reservation boundary at Birdtown; Bunches Creek (a Raven Fork tributary); the fish ponds in Big Cove community (fed by Raven Fork River); and Soco Creek, which is bordered by U. S. 19 East of Cherokee.

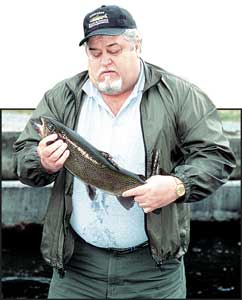

Most of the stocked fish are 8- to 9-inches long and weigh about 1/2 pound, but Ensleys’ crew also releases 1,000 trophy-size trout, each weighing more than 5 pounds — and some are much larger.

During 2001 for instance, the Oconaluftee gave up a 17-pound, 6-ounce rainbow to a teenager, and an adult caught a 7-7 brook trout from Raven Fork, Ensley said.

Ensley, a game-and-fish employee for more than 30 years and department manager for the past 9 years, said two-thirds of the trout his crews release are born in the hatchery at Straight Fork River, a major tributary of the Raven Fork.

A daily permit costs $7 and allows an angler to catch and keep 10 trout. Three- and five-day and season licenses cost $20, $28 and $200, respectively.

Children under 12, accompanied by a licensed parent or guardian, may fish free and the daily limit for these two anglers is also 10 fish.

Enterprise Waters are stocked twice weekly, and there is no size limit.

Public fishing is closed from March 1 to the last Friday in March, when heavy stocking takes place. Otherwise, you can fish from the last Saturday in March to the last day in February, seven days a week.

The Cherokees started their fishing program in 1964 with trout obtained from the nearby federal hatcheries at Erwin, Tenn., and Pisgah Forest.

The tribe’s completed its Straight Fork hatchery during 1984. Since then, the concrete walls of the raceways have gradually deteriorated, and for the past 3 years, Ensley’s workers been replacing the walls. When work is completed in the spring of 2006, this project will have cost $200,000.

“During 2004, we obtained 360,000 trout from 600,000 eggs,” Ensley said, “for a 60-percent survival rate.”

Many hatcheries around the country have a survival rate closer to 50 percent.

“We receive fertilized brook trout eggs from a hatchery in Utah, and rainbow eggs from several federal hatcheries around the country, including the one at Erwin, Tenn.,” he said.

There is some interesting history associated with the Eastern Band of the Cherokee Nation. During 1838 President Andrew Jackson ordered General Winfield Scott to round up the Cherokees and force march them to “Indian Territory” in Oklahoma. That devastating trek came to be known by the Indians as the Trail of Tears because so many Cherokees died during the harrowing journey.

But a few hundred avoided capture by hiding out in the Great Smokies, and there’s no doubt now their avoiding capture was a blessing for the Cherokees and present and future trout anglers.

Of the 16,000 Cherokees who started the Trail of Tears, at least 4,000 died en route to the Oklahoma Territory and many more perished later of injuries and illnesses acquired on the forced six-month march.

Fortunately, the Cherokees who hid from Jackson’s edict eluded capture and some of their descendants now provide what many consider to be the best commercial trout fishing in the United States. The Qualla Boundary’s public trout-fishing enterprise is believed to be the largest — and best — operation of its kind in the country.

At Bunches and Soco creeks during the dry months of summer, “dappling” is becoming a popular form of fly fishing. At that time of the year and especially at the small creeks, the trout can be spooky in the small pools.

At many stretches of these creeks, the canopy of overhead trees is low enough to prevent normal back casting, so that’s where local anglers developed dappling as an effective technique to present lures to trout.

The afternoon before opening day last year, Gene Shuler, a local fishing guide, fished Soco Creek east of Cherokee to demonstrate dappling.

“I keep a very low profile and use as long a rod as possible to avoid being seen by the fish,” he said. “I normally use an 8 1/2- to 9-foot rod and a 3- to 5-weight line, but I sometimes have to use a shorter rod where the creeks are too clogged with mountain laurel to permit the use of a long rod.

“In that case, you want to make sure you wear drab-colored clothing and move stealthily and very slowly upstream. Make only deliberate movements and avoid taking your feet completely out of the water when wading to avoid any kind of splashing or surface ripples.

“The need for stealth is paramount when dappling and magnified when you’re forced to use a shorter rod. When you’re only 6 feet away from your quarry, you need to be mistake-free to expect positive results. You should gently flip the fly to the head of the near pool,” Shuler.

The next step is to allow the fly to move with the current. When a trout strikes, the line will twitch, and the angler, with only a few feet of line out and pinching his line against the rod just above the reel, simply lifts the rod’s tip to set the hook. (A cane pole probably would work as well but wouldn’t look as impressive). Some anglers use strike indicators to help them see a trout smack a nymph.

But plenty of care to be noiseless is needed for this technique to work.

And, oh yes, be sure to wear felt-bottomed wading shoes. The rocks in the streams are slippery, and the water, even in summertime, feels like it came directly off a melting glacier.

Be the first to comment