Artificials can be more effective than live bait for Bogue Inlet flounder.

On a warm, sunny, calm day, Capt. Mike Taylor navigated his 24-foot bay boat through Bogue Inlet without a hitch until he hit the last set of breakers. As the boat crested the final wave and slammed down into the trough on the ocean side, he changed course eastward.

“We’ve been catching more flounder than you can imagine on the hardbottoms,” he said. “We catch anywhere from 70 to 100 flounder in a day, sometimes even more. About 25 to 50 percent of the fish will be keepers, and some will weigh seven or eight pounds.”

To some fishermen, that might seem like bragging, but by the time Taylor’s half-day trip was over, three anglers had landed more than 100 flounder, including limits of 15-inch keepers. A few years ago, Taylor discovered the flounder, which are so numerous they almost seem to be on top of one another other.

“I’ve been scuba diving to see what’s down there,” he said. “The flounder are beside the rocks, on the bottom between the rocks and even right on top of the rocks.”

But rocks and ledges create difficulties for anglers who want to catch flounder. They snag lines and lures, and they also attract other fish that chomp through dozens of live baits in short order.

“We started out fishing the Bogue Inlet ledges with live baits a few years ago,” he said. “Sometimes we rigged them on 2-hook rigs or jigs, but we went through baits so fast we decided to try using some artificial lures and jigs.

“We kept experimenting until we found the right combination of a 2-ounce Spro bucktail jig with a 4-inch Berkley Gulp! shrimp trailer. The big bucktail is necessary to reach the bottom. The Gulp! shrimp adds scent and flavor. Once a flounder grabs it, he usually gives you time to set the hook before he lets go. The main reason it works so well is that the lure looks just like a ‘finger-popper.’”

Taylor was once a commercial fisherman, and to a shrimper, a finger-popper is a mantis shrimp, which has modified claws for defense and offense. The claws pop outward against their target, which can be the fingers of a fisherman culling a shrimp catch, leading to the nickname “finger-popper.”

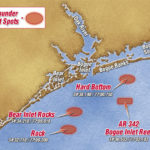

There are several rocky bottoms outside of Bogue Inlet. Taylor fishes Keypost Rock, Bear Inlet Rocks and other natural bottoms as well as the Bogue Inlet artificial reef, AR 342.

“At Bogue Inlet Reef, concrete pipes are the best places to fish,” he said. “They attract flounder because of their high relief. The holes in the pipes attract baitfish, which attract flounder. If you fish the concrete, the best bet is to fish right inside the pipe fields. Other anglers fish the outer edges of the pipes to keep from snagging their bottom rigs.”

Taylor slowed the boat once he arrived at his intended fishing area, about three miles from the inlet. He rigged a artificial shrimp on a bucktail, dropped it to the bottom, lifted it about the length of a rod, giving it a couple of small twitches, then let it fall back to the bottom.

“Flounder strike the lure as it falls or when it hits the bottom most of the time,” he said, “but they sometimes hit it on the way up. Most of the time, they strike right beside the structure. They might even hit the lure as it bounces right on top of a rock.”

Taylor kept the motor running as the boat drifted. The wind was calm, but a current of about two knots was flowing, moving the boat at a good clip.

“I use a 14- to 20-pound braid on my spinning rods,” he said. “I use a 40-pound fluorocarbon leader because it’s tough, easy to grab when landing a fish and the fish can’t see it. I tie the lure to the leader with a grouper knot.”

Taylor’s lure snagged a rock; he shifted the motor into reverse and began backing over the same track as his drift.

“You need a boat with a wide rear upper deck or a deep transom,” he said. “It should also be self-bailing. If there are any big waves, they can come right over transom boat while you’re freeing a jig.”

Once the boat had backed over the snag, Taylor tugged the lure free and resumed his drift. He bounced the jig on top of the rock, then down to the bottom on the opposite side.

“There he is,” he said. “It feels like a nice one.”

Taylor set the hook as soon as he felt the strike. He said any hesitation might give the fish a chance to spit out the lure.

“It’s not like fishing with live baits on bottom rigs, and you have to wait for the fish to swallow the bait,” he said. “You set the hook fast. You soon learn to tell the difference between a pinfish and a flounder by the way the fish bumps the lure. When in doubt, set the hook.”

Taylor and the other fishermen caught several flounder within the first 100 feet of drifting. Once the bite stopped, he motored back to the starting point to make another drift over the same hot spot.

“The flounder schools are scattered,” he said. “You might catch a dozen or more from one small area, so you keep going over it until you don’t get any more hits. Then you move to another spot.”

After fishing the ledges for a few drifts, Taylor moved to the Bogue Inlet Reef. Other boats were anchored around the area, and those fishermen were constantly dropping live baits to the bottom, reeling empty hooks back up and baiting them again.

He made several passes above one of the concrete junkyards, catching flounder on each drift. The action was consistant, with several non-flounder species landed, including a gag grouper and black sea bass, but most of the fish landed were flounder, and those flounder comprised more than one species, based on observations of the patterns on their backs.

Chris Batsavage, the N.C. Division of Masrine Fisheries’ lead flounder biologist, said the bag limit where Taylor was fishing off the beach had been reduced from eight to six fish, in part to protect one of those different species.

“The decrease in the bag limit was intended to reduce the recreational harvest of southern flounder as part of the Southern Flounder Management Plan to end overfishing,” Batsavage said. “The 15-inch size limit last year covered areas north of Browns Inlet, including eastern Pamlico Sound, Core Sound and Albemarle Sound. But the new stock assessment found we needed to increase the (minimum) size statewide.”

Batsavage said the restrictions intended to help southern flounder stocks rebuild should incidentally help summer flounder and Gulf flounder. All three species are caught near Bogue Inlet.

“Gulf and summer flounder share the some of the same characteristics so you have to look at them closely to tell the difference,” he said. “They both have oscellated spots on their backs. On the Gulf flounder, they form a large triangle pattern with two spots near the tail and one near the head, whereas on the summer flounder, they form a smaller pattern toward the tail. Gulf flounder have short, stubby gillrakers and more of them.”

Batsavage said there are times and places where Gulf flounder make up a good proportion of the catch. They prefer sandy bottoms, while southern flounder prefer hard structure areas.

“There’s no direct management plan for Gulf flounder, but they benefit from southern flounder and summer flounder management plans,” he said. “Statewide, Gulf flounder comprise less than five percent of the total recreational catch, but they can make up large proportions of some anglers’ catches at the nearshore ledges and reefs.”

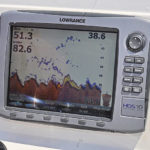

Batsavage said overfishing of southern flounder in the ocean is due to a combination of more anglers fishing reefs and ledges and those anglers having greater success through better education. He also credited better sonar and navigation equipment.

“We don’t know how effective the new regulations will be,” he said. “They should result in the reductions we need, and we will know during the next southern flounder stock assessment in a few years. But there’s always the possibility of more summer flounder restrictions at the federal level, which would impact fishing for Gulf and southern flounder.”

Be the first to comment