Lake Moultrie provides fishermen with great autumn action for bluegill.

Fishing for bream is simple.

You wait for a bright day in May, pack a light spinning rod and some redworms or crickets to fish under a bobber and ease around the shallows, dunking your bait near trees, logs or stumps. When you catch one decent-sized fish, you set up camp and load the livewell.

When May is over, you fish for some other species and wait a year, then repeat.

No consideration is ever given to where the bream spend the remaining 11 months, and if you accidentally come across one, you stare at it like somebody dropped an Easter egg in your Halloween bucket.

Now, here’s the secret. Bream live full and eventful lives throughout the year. They swim, they eat, they make little bream, they swim some more, and they try not to get eaten by other fish.

A good case in point are the bream that call Santee Cooper home. The fertile waters of Lake Marion and Lake Moultrie make for ideal reproduction conditions for bream throughout the spring and summer. Once water temperatures begin to cool off, the spawn-weary panfish migrate from the shallows to deeper water where they’ll spend the winter.

The Santee Cooper lakes offer very similar spawning conditions for bream: expansive shallow bays and coves lined and littered with standing trees and stumps, as well as a multitude of small aquatic and insect life for food.

The lakes’ deeper portions, however, differ a great deal. Lake Marion’s deeper areas contain standing and subsurface timber, while Moultrie’s deeper sections are comparatively devoid of vertical structure. Given this situation, the addition of fish-holding structure in the deeper areas — brushpiles sunk by local guides and anglers or fish-attracting structures planted by the S.C. Department of Natural Resources — draw bream like metal shavings to a magnet, especially on the lower lake.

“The status of the bream population on Lake Moultrie and Marion are excellent,” said Jim Glenn, an SCDNR fisheries technician who works out of the Bonneau field office.

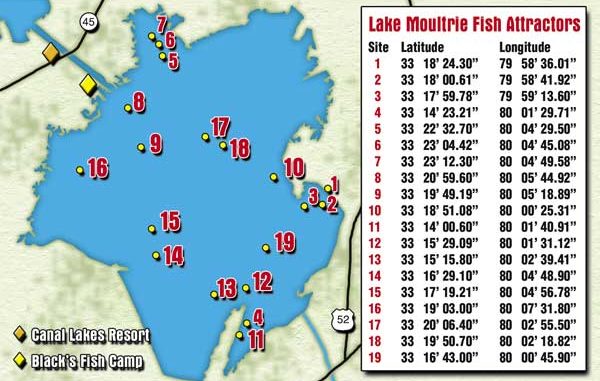

Glenn oversees the installation and maintenance of fish- attracting structure on the lakes. These structures, a combination of old Christmas trees, myrtle bush brushtops, and tree-shaped structures constructed of 1-inch black waterline, are placed in the lakes in locations where they’re likely to be run into by migrating bream. The attractors are normally associated with crappie habitat, and they are inhabited by crappie throughout the year.

“Crappie populations in any lake can be cyclical,” Glenn said. “This means that some years’ populations are high and some years’ low. On the other hand, bream recruitment on these lakes is extremely good, which means populations are good and have been for at least the last 10 years.”

While “bream” is an often- used collective term for a number of sunfish species, the bream that are drawn to the open-water brushpile habitats are bluegills. Santee Cooper is home to the world-record shellcracker, technically known as redear sunfish. Shellcrackers prefer a sandier bottom and more current. A shellcracker’s diet also requires them to inhabit areas where they can find freshwater mussels, snails, and other aquatic invertebrates. As such, shellcrackers are a rare, albeit welcome visitor to open-water brushpiles.

The “discovery” that big bluegills flocked to open-water brushpiles on Lake Moultrie was probably first made by guides fishing for crappie. Captain Spencer Edmonds of Eutawville has been guiding on Santee for 5 years, but he has fished the waters of the two lakes, the canals and rivers surrounding them for over 40 years. Edmonds spends a great deal of time during the months of January and February making and sinking brushpiles in both the upper and lower lakes.

“These are the same brushpiles I fish for crappie,” he said. “Starting in the fall, the piles in the lower lake load up with big bream. You can catch them on brushpiles on the upper lake, but there aren’t as many around the piles on the upper lake, and they don’t seem to be quite as big.”

Fishing from his 25-foot Crest pontoon, Edmonds and his business partner, Sparky, a Jack Russell terrier, locate their brushpiles by using GPS.

“Back in the old days, we used to line up trees or other landmarks on the bank,” Edmonds said, “but now I use a hand-held GPS and can go right to them.”

Once a brushpile is located, Edmonds throws out a marker buoy and begins systematically working the pile. With a transducer on his bow-mounted trolling motor, he can see what is directly beneath the boat on his depthfinder and get an idea how the brushpile is shaped.

“They’re funny sometimes, and they’ll stack up on one side of the pile,” Edmonds said. “If you just fish one side, you’ll think they’re not there, then you move all around the pile and find them, and you can catch a whole mess in that one spot.”

Holding to one spot can be a chore, especially on the lower lake where there is little topography to stop the wind. Windy days require Edmonds to mark his spot with a buoy, and then motor upwind and drop an anchor so his boat is positioned over the brushpile. Caution is urged when anchoring, especially around fish attractors planted by the state, not to hang the brush with the anchor line and pull it loose from the bottom.

Typical water depths for bream in the fall are in between 12 and 30 feet. Edmonds said that the shallower brushpiles work best earlier in the fall. Gradually, fish begin targeting deeper piles until they leave altogether for the winter. His favorite water depth for the peak of the season is between 18 and 22 feet.

Edmonds targets bream by presenting a bait vertically with a long, light-action rod. His bait of choice is a live cricket, hooking it on a small, gold bream hook.

Sometimes, bream will orient at the top of the brush, and other times they will be down in the brush or deep beside the brush. Needless to say, hang-ups are frequent. To combat constantly having to retie hooks, Edmonds uses monofilament line in 10-pound test.

“Ideally I’d use 6-pound, but with 10-pound I can usually straighten the hook out and then bend it back in place with my thumb,” he said.

Edmonds’ tackle choices are a 9-foot Shakespeare Ugly Stik crappie rod or a B&M Buck’s Jig Pole. The long rods make it easier to lower a bait vertically around the brushpile and are strong enough to horse a big bull bream out of the brush. These rods are matched with light action spinning reels.

The problem with using crickets to target bream is that you have to constantly rebait the hook, and you end up catching a lot of small fish. It’s also rare to catch anything but bream on crickets.

The alternative is to use small crappie jigs. Since bream have small mouths and tend to “pluck” at their prey rather than engulf it whole, jigheads poured with small, Nos. 4 or 6 hooks and tied with short hair or marabou feathers work best.

Another of Edmonds favorites is the 1-inch Berkley Power Nymph. The nymph baits work well on the smaller jigs and can catch quite a few fish before they have to be replaced. The small jigs are also attractive to Santee’s crappie population, and most of his client’s don’t mind splitting time between catching bream and crappie.

Be the first to comment