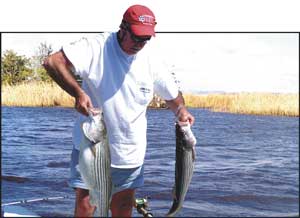

Striped bass fishing hits its fall peak during October at the Combahee River.

South Carolina boasts some of the best striped bass fishing in the country.The state holds the fish is such high regard it’s the official Palmetto State fish. The South Carolina Department of Natural Resources expends a tremendous amount of time, manpower and money each year to insure inland reservoirs are stocked with these hard-charging game fish.

The result has been a multi-million dollar industry. But what many South Carolinians don’t realize is a portion of our striped bass fishery when settlers first arrived in South Carolina exists on a self sustaining basis.

That population of stripers gave rise to S.C.’s freshwater inland fishery that exists in a landscape that pretty much looks the way it did years ago when settlers established crops of indigo and rice to make their living in the new world.

These are the striped bass of the ACE basin.

The ACE basin is the name given to the area of the state that stretches eastward between the town of Walterboro and the coast. It comprises the shorelines and coastal wetlands of the Ashepoo, Combahee, and Edisto rivers.

The rivers are freshwater but are tidally influenced, with the saltwater dividing line flowing back and forth with the tides.

During rice plantation days, a trusted servant would be stationed at the flood gates separating the rice fields from the rivers. The servant was supplied with a bar of soap and instructed that the gates were to be left open to the river “so long as da’ soap make lather.”

When the soap no longer lathered (the current stopped), the servant closed off the gates, preventing intruding tides and saltwater from ruining the rice crop.

Past years have seen a decline in the native population of the striped bass that inhabit the coastal rivers of the ACE basin, particularly the Combahee. During these years of decline, state biologists gave consideration to adding the coastal rivers to the list of hatchery-stocked waters to augment the population.

About this time biologists made some remarkable discoveries about the stripers that inhabited these water. Unlike their cousins to the north that enter coastal rivers to spawn and retreat to the ocean to live out their lives in the deep blue, the southern strain of striped bass never left their river environment.

Striped bass are found in all three rivers of the ACE basin, and it’s suspected each river maintains its own particular gene strain of fish that marginally migrate between the rivers.

These fish winter in the estuarine areas of the rivers near the saltwater dividing line. Summers are spent in the upper reaches of the rivers where natural spring-fed tributaries and dense tree canopies provide the necessary cooler water these fish need to survive.

A more intense study of seasonal movements of the striped bass in the Combahee was conducted in 2000 by fisheries biologists at Clemson University. This team, led by Dr Jeff Isely, electro-shocked fish native to the river during January of the study year and outfitted them with radio-telemetry transmitters.

The Clemson scientists tracked these stripers for the remainder of the year with the fishes’ exact locations recorded on a bi-weekly basis. Telemetry data indicated striped bass utilized the upstream areas, which afforded them the benefit of heavy shading from the dense overhanging tree cover during warm summer months.

These areas are 10 to 15 degrees cooler than the downstream rice-field areas of the river.

Movements consisted of upstream migrations during the early summer, then localized movement within the upstream tree shaded areas during summer, and a return to the lower river during late fall. Local anglers (rather than scientists) also found out the downstream fall migration meant hungry striped bass invaded the lower tidal reaches — with eating at the top of their list.

Ed Woodward, known in striped bass fishing circles as “Mr. Ed,” has fished the Combahee River for migrating fish since he was a teen-ager 50 years ago.

“I mainly target the lower reaches of the Combahee from a few miles above the U.S. 17 bridge down to Fields Point which is just a little ways above the confluence of the Combahee and St Helena Sound,” he said.

Woodward said striped bass in the Combahee system specifically target structure in and near the banks of the river to find ambush points to help them feed on unsuspecting prey.

Woodward said the prime season for fishermen to catch striped bass in this stretch is the period sometime before Halloween and ending near Christmas, with late October being the peak time.

That’s when the rivers are still full of shrimp and finger mullets, prime baits to use for the returning stripers.

The Rock Hill resident often has little time to arrive early enough to catch bait after the long drive to the Combahee. But he discovered he can substitute blueback herrings, readily available at many bait shops at Lake Murray, on his way to the river.

Blueback herring are like cotton candy to striped bass and are are anadromous fish (they can live in fresh and salt water) like striped bass, so the two species are at home in the ACE basin’s brackish saltwater.

Woodward uses his graph to check several of his favorite holes along the Combahee. Any deep hole can hold fish, but he likes deep water combined with a current break.

“The river has a couple of paved road and old railroad bridge crossings, and these are normally very productive spots,” he said. “In addition, there are some old rice-field dikes that have collapsed and stripers hide in the eddies behind the pilings used to hold the gates.”

Woodward said at times trolling can be productive if anglers use bucktail jigs with plastic trailers or shallow running crank baits.

“The problem with trolling is the tides often keep the river littered with plant debris,” he said. “Floating grass makes it difficult to troll without constantly freeing fouled lines.”

Woodward’s favorite tactic is to anchor upstream from a likely area and free line live baits back into holes. He said current and tides will dictate when and how much weight is needed.

A good starting point, he said, is to anchor at the upper edge of a spot and free line while drifting live bait across a hole, presenting baits with a Carolina-rigged down-rod with the butt set in a rod-holder.

Another striped bass veteran of the Combahee River is Nick Stratton, who lives in Walterboro, a few miles from the U.S. 17 bridge.

He said the October bite is probably the best time to fish the Combahee for striped bass. He also has success targeting these fish during their spring run, which takes place near the end of February and can last into early May, depending upon water temperature.

The target temperatures are between the middle 50 to 70 degrees mark. Once temperatures rise much above 70 degrees, the fish began looking for cooler water at the upper swampy stretches of the Combahee and its tributaries.

Without relying completely on a temperature gauge, anglers can judge the presence of fish by the availability of natural baits.

“Natural baits must be present for the striped bass to be in this area and active,” Stratton said. “Finger mullets will move into the rice fields as the tide rises and move back out when the tide drops.”

That’s the reason that Stratton always tries to fish with baits the stripers are targeting, including finger mullets and, at times, menhaden.

One of his favorite tactics is to position his boat above a likely ambush point, either a bridge piling or a collapsed dike, and back troll a bait into the hole.

“Sometimes I’ll anchor and drift baits back to them,” he said. “But I think a bait holding still in a moving current doesn’t look natural to the fish.

“There are lots of current movements — top currents and back currents, plus tidal currents. And that means everything is on the move.”

To simulate this with a hooked bait, Stratton will deploy two rods out the rear of his boat and use either the trolling motor or the big motor, depending on the strength of the current, to ease the bait back into his targeted area.

Stratton isn’t as concerned with depth of presentation as the tannic murky water of the Combahee makes the fish less spooky than fishing in clearer water. He also has found most of the natural bait moves in the upper one-third of the water column, and stripers are accustomed to looking up and coming to shallow water to feed.

“I want my lines to be angled back at about a 10- to 15-degree angle” Stratton said. “I’ll have enough weight on so that the bait is somewhere near the 10-foot depth. That’s deep enough for them to come up and get a bait.”

Stratton said he’s not talking about small fish all the time, although the majority of stripers caught from the Combahee aren’t giants.

He said he has caught and seen stripers in the 30-pound range come from this area, but that the average size was probably nearer to 5 or 6 pounds. It’s also not an area where anglers are likely to catch limits of 2- to 3-year-old fish, such as is usually the case at inland stocked reservoirs.

Juvenile stripers certainly will be abundant, which is a good sign for the continued health of the fishery. But they usually will be caught with a different pattern most of the time.

A good day fishing the Combahee will see three or four fish in the 6- to 10-pound range with an occasional line stretcher thrown into the mix.

As a bonus, Stratton said anglers also sometimes have nice red drum pound their baits when targeting the stripers of the Combahee.

Be the first to comment