The nearshore reefs out of Charleston are havens for lunker spadefish.

When Mark Melnyk ventured from Canada to South Carolina last year to film a handful of episodes of his World Fishing Network television show, Reel Road Trip, he happened on Charleston and Capt. Tom Siwarski of Carolina Aero Marine Adventures.

The speckled trout fishing had been okay, Siwarski said, but maybe Melnyk would be interested in a fish that he wasn’t on most anglers’ hit lists, one he wasn’t familiar with and that he’d certainly never caught before — one that was really biting.

Melnyk took the bait, and a day or two later, he found himself listening to the drag on his spinning reel screaming in protest, cackling with delight as he tried to keep a spadefish from diving down into the structure of the Caper’s Reef and cutting him off.

“Wow! My first spadefish,” he said, still panting from the exertion of the 5-minute struggle. “What a fighting fish. They’re so powerful. I can’t say enough about how much fun it was to catch this fish.”

And that was only a medium-sized one. When he capped the day catching a fish that pushed eight or nine pounds, he was hooked, literally, on spadefish.

That was no surprise to Siwarski, who will start taking parties to the nearshore reefs later this month to tie into spadefish, a warm-water reef dweller that looks like a huge, silver-and-black aquarium angelfish.

But it acts like anything but an angel.

“It’s like a bream on crack,” he said.

Siwarski and Capt. Mike Waller of Saltfisher Charters on Kiawah Island are thrilled for every chance they get to put a party of fishermen on spadefish, which arrive off the South Carolina coast when the water starts to warm up in the spring. They’ll stay through the summer, hanging around nearshore reefs in 30 feet of water or more, often swimming in big circles just below or at the surface in schools that may contain several dozen fish.

Giving fishermen a chance to actually cast to individual fish is enough of a rush, but there’s no describing the fight spadefish put up once they feel the hook. Their slim, deep bodies and big, powerful tails give them the ability to run and take drag with ease or turn sideways and resist efforts to drag them to the surface.

“They fight like a freight train,” said Siwarski (843-327-3434), who starts checking nearshore reefs like Capers and the Charleston 60 on a regular basis from mid-April through the first of May.

“One day, they aren’t there, and all of the sudden, they’re there — and they’re there to stay. They don’t go anywhere. They’ll stay through the end of July, at least.

“I’m usually finished with them by the first of July, because the later you get in the summer, the more it seems to me that the barracuda move in on those reefs and wrecks, and that will put the spadefish down on the reef instead of them coming up to the surface.”

Waller is usually already fishing the Lowcountry Anglers reef or Kiawah (4KI) reef for other species when the spadefish arrive. They’re typically all over the reefs by the first of May, and he catches them into August most years. In fact, he’s run into them as late as September.

“I don’t have it down to 70 or 72 or 74 degrees as to when they show up, but when we get some nice, warm, sunny days and the water has warmed up, they start showing up,” said Waller (843-343-8538), who runs most of his trips to the Lowcountry Anglers reef.

The four artificial reefs have some basic features in common. The 4KI and Lowcountry Anglers reef are in about 35 feet of water; the Capers is in 45 feet of water and the Charleston 60, as its name indicates, is in 60 feet of water. Each is spread out over a fairly wide patch of ocean and made up of barges and various other sunken watercraft, plus concrete and rubble from the old Cooper River Bridge. The Lowcountry Anglers reef is within three miles of the Stono River inlet; the 4KI is four miles out of North Edisto Inlet, and the Charleston 60 and Capers inlets are 12 miles out of Charleston Harbor.

Once spadefish are on a spot in good numbers, fishing can either be at or near the surface or down on the wreck. Sometimes, it’s a matter of time of day, sometimes it’s how smooth or rough the ocean is on a particular day.

“Early in the day, you’re more likely to find ’em up on top, finning, and sometimes, it seems like they’ll stay up all day,” Siwarski said. “The later you go in the day, if they’re not up on top, you can locate ’em on your (depthfinder). I’ll go to the highest relief on the reef or structure I’m fishing; that’s where I’ll usually find ’em.”

“If it’s a calm day, they’ll come up to the surface. You can chum ‘em up close enough to the boat that you can pick out the one you want to cast to,” Waller said. “If it’s rough, you might not see ’em.”

But they won’t go far, and once located, it’s not too much trouble to make ’em bite. In fact, it’s just a matter of putting a tiny piece of bait in front of ’em in a natural manner.

Siwarski has caught spadefish on two baits: shrimp and pieces of cannonball jellyfish. Those are also Waller’s two favorite bait, but he’s also caught them on pieces of squid.

When spadefish are finning at or close to the surface, the tackle is fairly simple: a medium-action spinning outfit spooled with 15-pound test fluorocarbon and a relatively small hook between Nos. 1 and 4. Specifics aren’t important, but Siwarski uses a 7-foot CastAWay rod and X-tra strong Owner hooks. Waller goes more for a Kahle, live-bait style hook. Both will add a small split shot if the fish aren’t at the surface, and sometimes, if Waller needs to float a bait to spadefish that are on the surface but out of casting range, he’ll clip on a float a foot above the bait and drift it back to the fish.

When Siwarski locates fish down on the reef or wreck, he’ll often set up a series of drifts over the spot, picking up a fish or two every drift. Waller likes to anchor up, because he’s not always targeting only spadefish, and he feels like the groups of fish swim circles around the reef structure; his fishermen will catch one or two every time the circle comes around his boat.

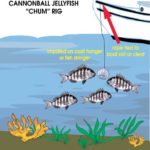

A third method to get sheepshead to bite is to chum with pieces of cannonball jellyfish, either cutting the jellyball into pieces and pitching it overboard to sink, or impaling a jellyball on a fish stringer or coat hanger and lowering it to the wreck, then easing it upwards as the fish become interested.

The bite is, in Siwarski’s words, “real light. You don’t need to really set the hook when you feel it, just lift the rod tip.”

After that, hang on.

Be the first to comment