Scouting and patience are the two keys to working this region’s early season gobblers.

For most South Carolina turkey hunters, nothing is better than hearing several longbeards booming gobbles at dawn on Opening Day.

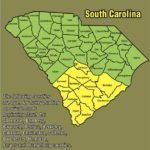

But for many, there is a way to improve on the scenario — to begin the season in the South Carolina Lowcountry.

Hunting gobblers in the Lowcountry carries with it several advantages. First, you get a two-week jump on the rest of the state. Second, gobblers are typically hammering their heads off by the middle of March.

Finally, there are plenty of places that offer exceptional hunting opportunities.

Those are some of the reasons why guide John Coit always opens his season in the Lowcountry.

“By March 15, when the season traditionally opens, the gobblers are full-bore, wide open, gobbling their fool red heads off,” Coit said. “But I’ve learned from many years of hunting (that) these birds are sort of a different breed when it comes to being successful hunting them. They are hunted hard every season, and they have a lot of terrain ideally suited to their survival.

“To be consistently successful, you’ve got to have a good plan, do your scouting and be willing to work hard for these birds.”

Coit lives in Florence, but he begins his season guiding for Bang Collins at Bang’s Paradise Valley Hunting Club. Collins has a 10,000-acre paradise with headquarters in Ehrhardt but with tracts of land scattered throughout the Lowcountry.

“One of the first keys to success in the early season is to have access to different types of hunting areas,” Coit said. “That’s one reason I enjoy hunting and guiding here, I have a lot of choices on different types of habitat to hunt.”

Collins said that key areas during the first couple of weeks can change dramatically, even from day to day.

“The old toms are gobbling hard, but they usually don’t reach the peak of breeding season for another couple of weeks,” Collins said. “To be successful, hunters have to be willing to change locations quickly. Access to swamps, hardwood bottoms, open pine plantations, cutover timber lands, controlled burn areas and chufa and other green food plots are ideal in terms of distinctive places where gobblers will be found.”

Coit, and Bang Collins’ brother, Tom Collins, guide extensively for turkeys and have developed what they call the “Lowdown on Lowcountry gobblers.” It’s based on years of experience in this area and a phenomenal success rate.

“Compared to hunting the rest of South Carolina and really throughout the South or anywhere for that matter, these birds have some unique characteristics,” Coit said. “First of all, we open the season early. Typically, the birds are often still flocked up, and that does make a difference. Plus, while the weather is seasonable, it is highly unpredictable during mid-to-late March. We may be hunting in warm sunshine one morning but have to face a cold, driving rain that afternoon. Or it may be 28 degrees in the morning and 70 degrees in the afternoon. Be prepared to hunt comfortably in these extremes. That is a key to success.

“Plus, these are basically flat-ground birds,” Coit said. “There’s a little elevation change from the swamps and hardwood bottoms to the pine plantations and green fields, but not much.”

Tom Collins said that creates detection issues for hunters not accustomed to hunting flat land.

“There are few ridges or contour changes to hide your movement,” he said. “First of all, a hunter must adapt to thinking about a move before getting up. The gobbler may be 250 yards away, but he may be able to see a quarter mile.

“Second, there can be property boundary issues. Even on a huge place like ours, we have to be very careful to stay on our property. In this flat land, you can hear a gobbler a long way off, but there are simply times he’s off the property that you have permission to hunt, and you sometimes simply can’t get to him or call him to you.”

But Collins said there’s some good news regarding this issue.

“During the early part of the season here in the flat country, gobblers will travel long distances during the course of a day,” Collins said. “I spend a lot of time scouting, even during the mid-day, and sometimes follow the travel of a gobbler by making him gobble at various times throughout the day. Gobblers will often make a 3- to 4-mile loop during the course of a normal day of looking for hens.

“That’s why scouting is so crucial to Lowcountry success. You may get on a gobbler too late one day — he may be out of your area — but if you know where he’s been, or where he’s headed, you can get on him. In their walking, I’ve heard gobblers where they were not on our land, but a couple of hours later I pick them up again where I can hunt him.

“Now, I have an approximate time and a place, and by being in position early the following day, we can sometimes take that bird. They don’t always make the same loop, but in general it’s a fairly dependable scenario in our area. Turkeys down here do like to roost in the same general area … and they do have a routine they use when not pressured too hard. I’ve used this mid-day scouting technique countless times to put clients on big, hard-walking, loud-gobbling birds. “

Coit has developed his Lowcountry expertise by hunting there for several weeks each season, as well as many other areas later on. With upwards of 60 days or more in the turkey woods each year, Coit has learned a lot about chasing gobblers and how to specialize in Lowcountry birds.

He uses one overriding philosophy that embraces all of his turkey hunting techniques.

“Patience is my No. 1 asset for killing turkeys in the South Carolina lowcountry,” Coit said. “Of all the things most turkey hunters can do that will help them see and harvest more longbeards, is to liberally add patience to their arsenal of turkey hunting techniques.

“Far too many times when I was just learning about hunting turkeys down here, I’d call, and a bird would answer, then get quiet. I’d wait what I felt was ample time, and then get up to move on him. Many times, as soon as I moved, he was close to me and looking for a hen. Often the gobbler was in shotgun range, but I had no chance to make a play on him. That’s one of the tendencies of Lowcountry gobblers. You may get that one strong gobble to your call and nothing else, but he may come right to you.”

Now Coit has added a great amount of patience to his hunting style.

“If I’m sitting on a good food plot, which is a place a gobbler may want to come anyway, I’ll give them a long time to get there, especially if he gobbles at my calling,” Coit said. “A chufa patch, like the many at Paradise Valley, is a place he wants to come anyway. It’s a place for hens as well. So he’ll come here not only to eat, but to get with other turkeys. Many times you’ll see strut marks in the fields as well as scratching for food.

“If a bird gobbles at me, I’ll wait an hour, maybe two” Coit said. “This is particularly effective during the mid-morning or mid-afternoon time period,”

Coit said you can stay too long, but generally, if a bird gobbles, he’ll give him over an hour to filter in before even considering leaving.

“Sometimes the birds will not gobble coming in;, they’ll just show up,” Coit said. “If you’ve got your decoys set right, they’ll focus on the decoys and come to them in a manner where you can get a good shot.”

In fact, decoy management is another strong point of Coit’s game plan.

“I don’t always use decoys, but many times I do,” he said. “Just seeing another turkey can often help a gobbler feel at ease and come on in. I think decoys are very helpful in a food-plot situation. I’ll set my decoys in a manner such that they will be facing the woods, trees, or other cover, as if they’re leaving the field. I’ll set a hen decoys at the edge of the plot, as if she is leaving the field right then. A jake decoy will be facing her but slightly behind. I’ve watched gobblers sneaking in being very cautious, and then see this decoy setup. Typically, they will come right on in.”

Another method for taking a gobbler in quick fashion is the “flash hunt” as Coit calls it.

This is a situation when most hunters get too aggressive and spook the bird when it is very killable.

“If I make a call in an area that’s fairly open, and a gobbler cuts my calling off with a hard, aggressive gobble, I have to make a quick choice,” Coit said. “One is to try to get closer to the gobbler, which is usually a good thing, to cut the distance. However, if the ground is open and a gobbler can see a long distance, many times I’ll simply have to find cover right where I’m located. For that reason, I usually look around before I make a call at all in that situation. If I do strike a bird that’s too close to move on, I can quickly set up and have a play on him.”

Coit also suggests hunters use caution when setting up. Open pine plantations near a hardwood bottom are inviting, but difficult to hunt effectively.

“These birds are very nervous, and a hunter sitting against a pine tree in an open pine stand just sticks out. Unless there’s a lot more cover than just a big pine, you’re taking a big chance of being seen. Also, getting in the hardwood bottom with him can help conceal you better, but remember, you are literally in his bedroom. Good setup selection here is as critical as good calling.”

Coit will go where the birds are, but if he hasn’t patterned a gobbler on a specific tract of land, he likes to stick with the swamps and bottoms.

“I’ll generally have more plays on birds in a day if I stay in the swamp bottoms,” Coit said. “Unless I’ve got a bird roosted elsewhere, I start and end the day in the swamps or hardwood bottoms. It takes a special kind of idiot to want to get into the swamp in the pitch-black dark to set up on a gobbler. But that’s where they like to be … so that’s where I like to be. I do wear and strongly recommend waterproof snake boots as the footwear of choice.”

Calling is another strong suit of Coit’s. He is a master of numerous calls and uses different calls throughout the day.

“You can certainly overdo a good thing,” Coit said. “If I call a bird using a particular call, generally that call will be much less effective on that gobbler in the future. Even if the gobbler isn’t spooked by a missed shot, if he works in and we can’t shoot, it seems he will remember that specific call. He may gobble at it in the future, but he’s not likely not work it. That’s why I’ll usually hold some calls back for emergencies. Then I have a play on a bird that’s been worked before by using a totally different sounding call.”

Coit prefers the glass Perfection call as one of his favorite weapons for locating and calling gobblers in close. But he’ll use box, slate and mouth calls as well.

Coit’s final trick for Lowcountry birds is to work a gobbler with hens. During the early season, birds being henned up can be a real problem. Coit acknowledges this can be one of the most difficult tasks in turkey hunting, but it can be done. Coit’s advice is again use a heavy does of patience.

“To me, the key is not messing up the bird by being seen,” Coit said. “As long as he doesn’t know you are a threat, you still have a play you can make on him. Sometimes, you may have to set up two or three times. Sometimes, you may have to just be pinned down and wait until the hens leave him. Also, you can sometimes get into a calling ‘fight’ with the dominate hen with him.

“When this happens, you can sometimes call the hen to you, and the gobbler will tag along for the show,” Coit said. “My clients have taken many gobblers through the years using these techniques.

Coit added that if the hens drag the gobbler away, that’s the time to move and try to get in front of them. Otherwise, being patient is typically the key to success.

“Most turkey hunters are simply overanxious,” Coit said. “Turkey hunters need to have patience and try to figure out each gobbler as an individual bird. Each gobbler wants to be treated in a different way, it seems. Some like aggressive and loud calling. Many prefer soft and subtle. That’s why I use several different calls.”

Be the first to comment