Summer stripers and hybrids mean deep-water fishing, and getting baits deep means down rods.

It’s hard to say for every species of fish that when a particular pattern is really working, that it’s the way those fish have to be fished for.

Take for instance, you decide you want to fish for striped bass — or their hybrid cousins — this month. Unless your favorite lake has some sort of cold-water discharge area, you’re going to have to fish in deep water.

To target stripers in deep water, you’re going to have to fish deep, and aside from a handful of heavy metal trolling or jigging tactics, you’re going to have to master the use of the down rod. Down-rod fishing for striped bass involves simple tools that have to be used together in a precise order to be consistently successful.

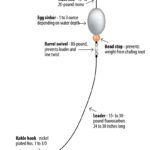

A down rod is basically a medium to medium-heavy action rod spooled with 15- to 20-pound monofilament. On the business end is a basic Carolina rig: of a heavy weight, a barrel swivel and a 2- to 3-foot length of leader — mono or fluorocarbon — tied to a live-bait hook.

Chip Hamilton, who guides on South Carolina’s Lake Hartwell, seconds the idea that unless you’re fishing some type of cooler, river system, down rods are about the only way to catch mid-summer stripers. To break that down even further, Hamilton has two basic patterns that he follows to put his clients on fish.

“Most of the year, you’ll find hybrids and stripers schooling together, but the exception is in July when they tend to separate for a time,” he said. “Most of the striped bass are going to head for the main-lake basin to find that deeper water, but because the hybrids tolerate warmer water a little better, they don’t always follow.”

Hamilton’s first tactic is to look for fish holding on a bare hump in deep water — in Hartwell, that’s 45 to 70 feet. Long points are typically placed in this category, but Hamilton prefers a strict hump, perhaps and old river-bend ridge or just a high spot surrounded by deeper water.

“These locations have good oxygen at those depths, and it’s a good place to feed,” said Hamilton, who compares the scenario to a clearing in the woods where deer congregate to feed. When he marks fish on his graph, he drops live bait to the bottom on a Carolina rig and reels up about three turns of the handle.

“We put the rods in the rod-holders and I hold the boat still or maybe just bump around with the trolling motor,” he said. “When one fish commits to a bait and we get hooked up, the action is usually fast and furious until the school moves back off the hump. By then, we’re well on our way to a limit.”

Hamilton’s second scenario is similar but involves much deeper water. He looks for a break in the bottom structure into which fish will move.

“In a lot of impoundments — and this includes Hartwell — they didn’t cut the timber, they just topped it off at certain depths, so you might be in an area that’s 100 feet deep but the trees come all the way up to 40 feet,” he said.

In this situation, he looks he’s for a low spot, or even a bare spot, in that old, submerged forest. If he finds a low spot where trees were cut 20 feet instead of 50 feet off the bottom, he’ll put his baits in the hole while keeping them out of the structure on the bottom.

“It’s the same principle. I’m looking for an open spot, in this case a low spot or a bare spot in the surrounding forest of trees,” he said. “The baits are even with the surrounding trees, and stripers will swim out of the trees into the open area to eat the baits.”

Hamilton uses only live blueback herring for baits, opting against gizzard and threadfin shad or bait-shop shiners.

“I can remember fishing in Hartwell with my dad when I was a kid, before there were herring in here,” he said. “The stripers would school up out of deep water, but they were the poorest fish you’d ever seen — long and skinny and no meat on them. They looked like they were starving.”

The introduction of blueback herring presented striped bass and other predator fish with an alternative, a forage bait that preferred to stay in deeper water and showed a similar intolerance of warm, low-oxygenated water.

“In lakes where a solid thermocline forms, all of these fish — the stripers and the herring — will be right in the top of the thermocline,” he said. “That’s not always a hard and fast rule on Hartwell because of how they pull water, but it does mean a much healthier striper on the end of your line.”

Be the first to comment