During August nights, the Cape Fear weaves a magic web of peaceful slumber for some and river giants waiting to be caught for others.

The Cape Fear River lowlands become unbearably hot each summer.

It doesn’t help that the riverbanks are high and steep, blocking all but the strongest winds from giving relief from an overhead sun and humidity hovering near 100 percent.

Summer was full blown; only a few boat trailers sat at the parking lot of the Corps of Engineers Tory Hole ramp at Lock and Dam No. 2 at the Cape Fear River near Elizabethtown.

Families used the park’s picnic shelter for shade while a few visitors tested the tepid water by tubing and swimming. Visible anglers were few, mostly children drowning worms, attempting to catch sunfish.

But as shadows began slanting, those who know how to fish the river began to stir. A 20-foot Bently pontoon boat launched and idled at the ramp, her aluminum toes tickled by river rocks. Web Weaver, printed across a pontoon, hinted at her purpose.

Brian and Ellie Newberger made last-minute preparations aboard the boat while a canvas canopy sheltered them from the sun. It also would shield them from night dew or rain or wind accompanying any summer thunderstorms.

As extra protection, they added a tarp to the factory cover, extending a plastic layer of overhead protection from stem to stern.

At her stern, Web Weaver sprouted 17 fishing rods with yellow tips. The reels were Penn saltwater trolling and casting models 9, 109 and 209, with a few Squidders in the mix. Not to discriminate, a couple of rods sprouted Shimano and Shakespeare reels.

“I’m only fishing 17 rods tonight,” he said. “Sometimes I fish more than 20. Tournaments allow eight rods per boat. But we’re fishing for fun tonight and there’s no limit on fun.

“I really like the old Penn 209s the best, but I remove the level winds so they don’t hang up.”

Using 17 rods at once sounds more like work than fun, even if you disregard the expense. But Newberger picks up reels wherever he finds deals (at garage sales and pawn shops). He pays more attention to rods, preferring 10-foot Bass Pro Cat Max and Bass Pro’s Power Plus heavy-action designs.

While the uninitiated can only guess why anyone would need so many rods, an expert like Newberger knows it takes setting lots of baits to catch blue and flathead catfish from the river. No one should cast any doubt about Newberger’s style of fishing because he caught the state’s record flathead catfish (78 pounds) from the river Sept. 17, 2005. He released the monster cat the following day.

It’s likely she weighed even more when she was caught. But Newberger had to hold her several hours until a marina with certified scales opened.

“I called the person who operates the scales at the marina because I knew the fish was a North Carolina record,” he said. “But it was early in the morning, and she wouldn’t come down to weigh the fish until regular hours.”

Some folks are night owls while others need their sleep — or don’t get as excited as Newberger about a record catfish.

But any state-record fish —to the fisherman who caught it — is the trophy of a lifetime.

While the record flathead was huge, she wasn’t the biggest Brian has hooked. He said he has lost battles with world-record catfish.

Newberger used the rest of this afternoon light to scout his fishing territory. He and his wife took turns navigating and watching twin depth-finders. One sonar was located at the bow and another on the console.

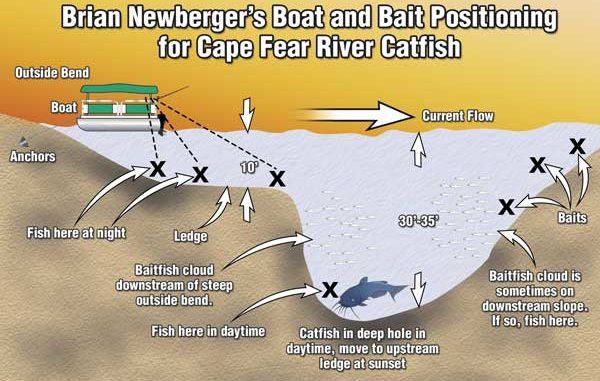

With their underwater eyes they found deep holes at the outside edges of river bends, identified cloudy patches as baitfish and saw marks that looked like suspended catfish.

“I’ve hooked catfish I know weighed over 100 pounds; I think there’s a world record lurking in the Cape Fear,” he said. “In 2006 I spent a week catching bullheads and bream as big as your hand for baits and fished every night. I hooked a big flathead on 1-pound bream. I finally got the fish up to the top, and he broke the line on a stabilizing cinder block. That’s happened twice with 100-plus-pound catfish. There’s no margin for error when it comes to landing the big ones.”

Once he found a steep drop at an outside bend of the river, he set a pair of grapnel anchors at the bow corners. He no longer uses cinder-block stabilizers tied to stern as secondary anchors since he lost the two big fish because of them.

“Catfish move into deep holes during the day then come to shallower flats upstream at night,” Newberger said. “I don’t like to move around much after dark. It’s too much trouble to reel in, re-anchor and re-bait all the rods.”

His wife netted a shiner from the livewell and handed it to Newberger. He put the bait on a hook and cast it into the river.

“I don’t fish as much as Brian,” she said. “But I like catfishing at night because it’s so peaceful.”

Besides finding the best holes, having enough of the right kinds of bait is the biggest obstacle between an angler and a trophy catfish. Newberger uses many different baits until the fish show a preference.

He has aerated live wells at both sides of his boat big enough to keep a 200-pound catfish alive. He fills them with sunfish and shiners caught on hook and line and live eels bought at tackles shops. He uses shiners, shad, eels and sunfish for baits, cut into chunks or alive.

He said small bullheads make top baits for flatheads. He catches them at creeks because native bullheads have been supplanted by the Cape Fear’s non-native flatheads.

His wife grilled hamburgers while Brian set his lines. He casts baits all the way across the river, using 4- to 6-ounce river sinkers with flattened teardrop shapes and longitudinal holes through the center; they resemble egg sinkers smashed on a railroad track. The flat shape keeps them from rolling in the current.

Between burger bites, his wife retrieved baits from the live well and handed them to her husband. He hooked live shiners, bullheads, eels and sunfish on 8/0 circle hooks. He also used cut shad and eels with several rods.

“Blues like cut baits and flatheads prefer live baits,” Newberger said. “You never know what’s going to work, so I always give them a choice.”

The first catfish bit as he was biting his burger. It was pandemonium as the 15-pound blue catfish tried to weave a quarter of the lines into a cobweb. But Newberger maneuvered the fish free of potential tangles as handy as knit one/pearl two.

“A big blue can tangle lots of lines,” he said. “A flathead is worse because he goes where he wants until you wear him down. A big flathead can fight an hour on 30-pound line. You lock the drag, move around the boat and do whatever you have to keep them out of log jams. If he wraps a log, he breaks the line.

“You keep him out of the other lines if you can. But if the line catches other lines, you play the fish and worry about untangling the lines after you land him.”

To keep baits on the bottom, Newberger ties a giant version of a bass angler’s Carolina rig, with a swivel, 8/0 circle hook and 50-pound fluorocarbon leader. The line runs through the hole in the sinker to the swivel, allowing the line to slide when a fish bites.

For fishing cut baits, he adds a Styrofoam float to the leader to keep the bait above the mud. Blues sometimes pick up the bait several times, shaking the rod before deciding to eat. The sliding sinker telegraphs these subtle strikes.

But flatheads strike live baits flat out. They’ll hit baits fished with bottom rigs, but Newberger also uses a trolley line to cast a surf sinker with protruding wires to the bank. He uses the trolley rod the same way as a pier angler fishing for king mackerel, sliding a release clip holding a live sunfish from the fighting rod along the trolley line to keep the baitfish swimming just beneath the surface. To retrieve the sinker, he navigates to the bank and gives it a tug. Whether hung in the mud or on vegetation, the wires fold to release the sinker.

Newberger continued setting lines as darkness fell until he had all his rods in holders across the stern. He rediscovered his cold, partially-eaten supper and switched on a light. He’d rigged six amber vehicle-clearance lights inside white PVC pipe along the stern. The lights pointed upward from a groove cut into the pipe, illuminating his high-visibility lines and yellow rod tips until they looked like a radioactive spider web. The tip of each rod was painted fluorescent yellow to reflect the amber glow.

He used different types of baits with his rods but remembered what bait was where and watched them for activity. No flatheads paid a visit. But the blues came calling steadily.

Several times, a catfish fondled the bait, bouncing the rod tip before letting the bait drop. Such behavior indicated a blue cat.

“They stick around and bite again,” Newberger said. “Sometimes they keep hitting the same bait or they might move to another one — they’re picky.”

Only one boat went by as darkness fell, heading to the ramp before it got too late. Brian heard the engine and moved a line from the center of the river so the boat could pass.

“Once it quiets down, you can cast lines all the way across the river,” he said. “A catfish can be anywhere. So if you cover the water all the way across any catfish moving upstream or downstream will find your bait.”

The Newbergers usually fish Saturday nights, remaining on the water all night, enjoying the stars, serenity and coolness. Newberger prefers to stick with one spot but occasionally moves to another hole if the fish aren’t biting.

“I don’t get to come with Brian often,” his wife said. “But I got someone to watch my daughter tonight so I could be here. Brian does most of the fishing when I’m along. I just enjoy being out at night on the river with him.”

She watched her husband catch a few blues, then retired to a folding camp cot to catch a few Zs. Mosquitoes whined and DEET aerosol scented the air. Ellie said she was going to buy a ThermaCell insect repellent device for a gift so her husband wouldn’t have insect repellent on his hands while he was fishing.

“You never knew what might keep a fish from biting,” she said.

Newberger caught 12 more blue catfish; the largest 20 pounds. Nevertheless he was disappointed he didn’t catch a flathead.

“You don’t catch as many flatheads as blues because they’re territorial,” he said. “Blues are schooling catfish and don’t have all that competition going on.

“If you fish near a logjam, you can catch a big flathead or two, but you could catch 20 blues. On a typical night, I’ll catch 24 flatheads and blues combined.

“I thought about moving when the bite was so slow. But you never know when a big one is going to hit, so I stayed put.

“It’s always a gamble.”

Newberger’s heavy tackle made short work of the blue catfish. Once he had a fish coming toward the boat, he kept reeling until it rolled at the surface. Then he scooped up each Mr. Whiskers with a cavernous landing net before he let it go.

The last blue catfish was one of the biggest. The clicker on a big Penn reel awakened Ellie as the catfish struck. The fish’s tail slapping against the deck after it was netted and Newberger brought the fish to the stern for a look.

While landing the catfish, Newberger began yawning. He’d fished all night after working all day as a forklift operator. However, the lack of shuteye was nothing new to this angler who stays pumped up for the next big bite.

While his wife didn’t land a fish, she’d also gotten what she wanted.

Web Weaver wove her a blanket of peace, while the waters of the Cape Fear lulled her to sleep, lapping a metallic lullaby against the aluminum pontoons.

Be the first to comment