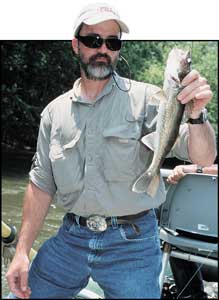

Cherokee float trips produce smallmouths, rock bass and walleye.

A light mist rose from the surface of the Oconaluftee River early last June when our two-car group pulled up to the only decent spot to put boats in the river below the Luftee Dam.The steep bank that had to be negotiated to launch guide Gene Shuler’s two boats wasn’t exactly what a river boat angler would normally choose, if he had a choice. But this launching spot would have to suffice, because it was the only one available.

Four of us planned to float and fish the Oconaluftee River from the dam south of Cherokee to where it joins the Tuckasegee River, then to the U. S. 19 bridge above Bryson City, where we’d take out the boats.

It was a bit of a chore getting the boats down the bank, over some rocks and into the water, but after 30 minutes of lifting, pushing and skidding, the drift boats were in the water.

Linda Whitecar chose to ride with Shuler in his 16-foot Hyde Drift boat, while her husband, Terry, rode in Shuler’s 13.5-foot Star inflatable rubber boat piloted by Alan Rogers, a Shuler assistant.

Mrs. Whitecar had expressed a burning desire to learn how to fly fish for smallmouth bass, and she had chosen a capable teacher in Shuler, who’s been a fly-caster for 24 years and an instructor/guide for six years.

While this was her first attempt to catch smallmouths with fly tackle, he’d been using bait-casting and fly tackle to hook largemouth bass in his native Florida for many years.

Recently retired, Whitecar and his wife were taking advantage of his freedom from the daily grind to visit western North Carolina’s Great Smoky Mountains and try a few new fishing spots.

Weather-wise, it was a gorgeous day for fishing, but we faced a challenging problem — slightly turbid water initially and very turbid water later that morning.

Earlier that week, heavy rains had dumped a lot of silt into the reservoir above the dam, and some of the sediment was working its way downstream.

Immediately below the dam, the river water was a little too cold to suit most smallmouths, but we saw several trout rise to the surface as they engulfed rising insects.

Once his drift boat was in the water, Shuler spent several minutes assembling two fly rods and tying on Size 6 brown and green Wooly Buggers with orange heads, which he’s found effective for attracting at least four species of game fish.

“Brown and rainbow trout, walleyes, smallmouth bass and rock bass migrate up the two rivers from Fontana Lake each spring to spawn on the shoals,” Shuler said, “and sometimes we catch the five species during a single float trip down the river this time of the year. After spawn, some of the fish take their time returning to the lake.

“Our trout fishing is well known throughout the region, but we also have some great smallmouth fishing at the Oconaluftee, Tuckasegee and Little Tennessee rivers.

“The daily bag and creel limits are liberal and the season is open each month of the year. Most of the smallmouths we’ve been catching have been running from 1 1/2 to 2 pounds, but they’ve ranged from 1/2 to 3 pounds.“

For local streams, the daily creel limit for smallmouth bass is five and the minimum size limit is 12 inches. However, two of the fish may be less than 12 inches.

While Rogers’ boat was lodged at the edge of shore and he rigged two fly rods for Mrs. Whitecar and him, Shuler pushed off from shore and his boat drifted 100 or more yards downstream to a rocky run before he dropped anchor.

Shuler knew from past experiences bass and trout would hit the wooly buggers — if the fish were in a feeding mood and could see the lures.

Shuler and Mrs. Whitecar were still fly casting when our raft drifted by a few minutes later, but they hadn’t had a hit.

Our first stop was at a rapids around the first bend in the river and a mile or so below the dam, so we temporarily lost sight of our companions.

Rogers handed a ready-to-use fly rod to Whitecar, who quickly cast the Wooly Bugger to the head of a swift run below some large rocks. After a half dozen casts, his client hadn’t had a strike, but he patiently kept trying different runs.

Rogers attached a Size 7 jointed Rapala to the snap swivel at the end of his spin-casting outfit.

“This is my favorite plug for catching river smallmouths,” he said as he sent the artificial sailing from the opposite side of the raft toward an even larger run closer to the center of the river.

Whitecar continued to drift the Wooly Bugger through runs, but his hopes dimmed.

After about a dozen casts of the Rapala to several different runs, Rogers had had only one light bump, and that might have occurred when the lure struck a rock.

His next choice of a lure was a single-blade chartreuse spinner, which he considers to be a good back-up offering. He gave up on spinner after a dozen or so casts.

“I think we’d better try another spot,” Rogers said, as he pulled up anchor, and the boat started drifting rapidly downstream.

A long row of rough-looking fishing cabins, supported by stilts in the water, teetered at the edge of the north river bank overlooking our next fishing spot.

Considering how high this river rises after a heavy rain, it was amazing the cabins were still there.

Rogers dropped anchor at the edge of large, deep run below a rapids.

“It appears the water is a little too dingy for the fish to see our artificials,” he said, “so we’re going to try something a little different here — live salamanders. Bass can smell these lizards when they can’t see ‘em, and right now we need all the help we can get.“

Rogers replaced the Rapala with a Size 2 hook, which he inserted through the upper lip of the 3-inch-long salamander, then added a single small split shot to the line about 18 inches above the hook.

On his first cast to the large deep run, a fish picked up the salamander and started to swim away. Rogers let the fish go a short distance then reeled in the slack before snapping the rod upward and setting the hook.

The fish immediately put a sharp bend in his rod and gave a scrappy fight for several minutes before he reached into the water and lifted out a tired 15-inch smallmouth by its jaw.

“This is more like it,” he said, as he smiled and dropped the fish into the live well.

Before he cast again, Rogers added a similar hook and bait arrangement to an open-face spinning reel outfit he had brought along for his client. Minutes later, Rogers and Whitecar were battling smallies.

Whitecar brought in a smallmouth of about 12 inches, and the guide quickly followed with a large 10-inch rock bass.

As Rogers boated the goggle eye, the boat containing Shuler and Linda Whitecar came drifting into view as it drifted down the Oconaluftee. Minutes later, Shuler anchored slightly upstream and out from us, below a nearby shoal.

“Care to try the salamanders we’re using?” Rogers said. “We’ve caught a few smallmouths and rock bass, but the artificials haven’t been working.“

Shuler replied in the affirmative and grabbed the container of lizards Roger tossed to him.

Almost immediately after he and Mrs. Whitecar each tossed a live salamander to the head of a run below and to each side of their boat, they each hooked and landed a small bass. But the bite soon came to a screeching halt.

Rogers caught only one more rock bass, an 8-incher, while the other three anglers didn’t have a bite.

Our boats drifted down the river to where the Oconaluftee joins the larger Tuckasegee River, and while all four anglers tried their luck at that point, no one had a bite using salamanders.

By then the mid-day sun was high in a nearly cloudless sky and warming us considerably. But unfortunately, the Tuck was even muddier than the Oconaluftee.

Shuler said he learned later the high turbidity in the Tuckasegee was caused by sediment removed from the reservoir behind the Dillsboro dam.

Just before we called it quits, Rogers stopped our boat at a small pool below a rapids at the south side of the river. He lip-hooked another salamander and tossed it into a deep run next to the steep bank, the top of which was covered with thick shoots of bamboo.

The bait drifted only a foot or so before Rogers’ rod suddenly bent sharply toward the water, with the fish hooking itself. The sharp bend in the rod suggested this fish was larger than the others he’d hooked. Our guide, with a big smile on his face, soon lifted an 18-inch walleye from the muddy water.

By then Shuler’s boat was a long ways ahead of us down river, and it took some hard rowing for us to catch up. Shuler and Mrs. Whitecar had not had any bites.

A short time later, we beached the boats at the bank below Banner Farms, a fresh-produce operation, and the guides returned to their vehicles and trailers below the Luftee dam.

Obviously, all of us had been hoping one or more of the group would boat a really large smallmouth, but fishing conditions weren’t favorable and no 3-pounder was seen or taken.

Nevertheless, the Whitecars seemed satisfied with the results and remarked about how much fun they’d had and how much they enjoyed the scenery.

The magnificent scenery of the Cherokee Reservation’s two major rivers was well worth the trip. And bigger fish still are there, waiting for anglers to come visit under more favorable conditions.

Be the first to comment