Hunters don’t have to travel far, lease an expensive blind, battle crowded game lands or own a private impoundment to hunt January Canada geese.

The goose calls came from the east, directly behind five hunters hidden at a fence line that bordered a stand of hardwood trees in Orange County.

“Honk, honk, honk, a-honka, honk.”

Wearing camouflage clothing, caps and face masks, the five friends could see nothing in the sky because of the woods behind them but knew a flock of Canadas were flying toward them.

Each toting a 12-gauge auto-loading shotgun crammed with steel and other types of non-toxic shotshells, the men had driven in darkness to the northern piedmont farm, parked their vehicles, then grabbed their guns and dozens of goose decoys to spread in the field while the world was still asleep.

It took several minutes to walk to their chosen spot. The grass was wet and the ground was sloppy from recent rains.

“We’ve been seeing lots of geese in this field for weeks,” said Rick Poole of Efland.

***

Seeing lots of geese at North Carolina’s central counties these days isn’t unusual, particularly Canada geese.

It’s one of the anomalies of modern times that Canada goose numbers are plentiful across most of the state when other waterfowl numbers seem to be declining. With a seemingly endless string of warmer-than-usual winters that have reduced duck flights for several years — even as the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has noted overall booming duck populations along the various flyways — Tar Heel hunters haven’t had a really good duck season in recent memory. Usually, as duck seasons go, so go goose seasons — but not in North Carolina.

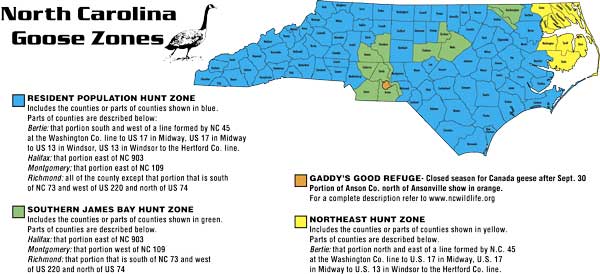

Even stranger, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission have put restrictions on shooting Canadas in the northeastern corner of the state because so few of these geese fly south along the eastern edge of the Atlantic Flyway to reach North Carolina. In fact, at the Northeast Hunt Zone (Currituck, Camden, Pasquotank, Perquimans, Chowan, the eastern half of Bertie, Washington, Tyrrell, Hyde and Dare counties), hunters are restricted to one Canada goose per day and required to turn in a report of their hunting trips or risk not being issued a hunting permit for the next season.

What’s also unusual is the Northeast Hunt Zone once was about the only place a N.C. hunter could find a Canada goose. Currituck, Dare and Hyde counties, in fact, were considered Meccas of duck and geese hunting, going back as far as pre-Colonial times. But legendary waterfowl hunting at the coast started its decline during the early 1960s after years of market hunting and sport shooting reduced what once seemed an unending supply of birds.

Today most of North Carolina’s Canada geese fly everywhere except the northeastern corner.

But while migratory Canada geese numbers have declined in the east, piedmont (resident) geese numbers have exploded. And they present golden opportunities for hunters who take the time to knock on doors and ask permission to hunt.

A retired worker at the county’s Department of Social Services, Poole had relatives in Orange County, in particular his uncle, Bill Ray, and Ray’s son, Kenny, who were landowners. Bill Ray, a farmer, also was a friend and neighbor of other residents happy to allow a scruffy group of goose hunters to set up decoys in their pastures.

Many of Ray’s friends, as well as he, own land that attracts Canada geese. His dairy farmer friends were more than happy to allow goose hunters on their property to reduce the numbers of honkers that annually invaded their land, ate their crops (corn, soybeans) and whose droppings sometimes carried diseases (salmonella, coliform bacteria) that sickened and had killed some of their cattle.

So the hunters were hunkered down at a fence line last January, listening to flying Canadas a few minutes after daylight. Just after first light, the birds had lifted off from a local reservoir where they’d spent the night, floating on the water, safe from predators such as coyotes and foxes.

Now they were hungry, headed for a green field to land and nibble breakfast from tender foliage.

However, hunting late-season Canada geese isn’t as easy as filling the eight permitted daily tags during the early September season. At the start of September, the birds are unwise to hunters; by January they are wary of anything that doesn’t look natural on the ground.

North Carolina has a fairly complicated set of goose seasons. Happily, resident birds can be taken almost the entire hunting season. The 2007-08 season dates were Sept. 1-29, Oct. 3-27, Nov. 10-Dec. 1, and Dec. 15-Jan. 26.

September features the early “state” season, while hunting after Oct. 1 is set within a framework offered to the N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Bag limits drop from eight Canadas in September to five geese per day during the post-Oct. 1 seasons (except for the small Southern James Bay Hunt Zone, where only two birds per day are allowed, and the Northeast Hunt Zone, where one bird per season can be shot).

After securing a hunting site, the next step to successful Canada goose hunting is purchasing decoys and knowing where to place them.

There are many types of decoys — silhouettes, hollow shells, motor- and even wind-driven models. For hunting small areas, it’s good to use as many decoys as one can afford (or have hunters combine their decoys). Two dozen decoys is a minimum number, although the more the merrier is the general rule of thumb.

“Shell decoys have the best price,” Poole said. “The cheapest ones cost about $120 per dozen. But more expensive, larger shell decoys can cost up to $350 to $450 per dozen. Full-bodied plastic decoys also work but can put a $300-for-12 dent in your pocketbook.”

Poole mixes silhouette decoys that look real and twist in the wind with shell decoys and a few full-bodied decoys that sit on stakes and also will move with a slight breeze. It’s an advantage to have moving decoys to get the attention of flying Canadas.

“Putting out decoys isn’t as simple as just setting them anywhere in a field,” Poole said. “You’ve got to take into consideration wind direction, if there is any, because geese like to land headed into the wind for a slower, safer landing.”

If it’s a windy day, Poole likes to place decoys in a “V” pattern, with the head of the “V” facing into the wind, leaving an area in the middle for flying honkers to land. If there’s no wind, an “X” pattern works well, with geese having four landing zones to choose while flying into at spread from any direction.

Some hunters like to put their decoys in family groups of four to eight, spaced apart with room for the birds to land between them, and with each decoy facing into the wind. It’s also a good idea to put a few decoys in the alert position at the edge of any spread. Canada geese, similar to crows, have “sentries” that watch for danger while a flock is feeding, so a spread with three or four sentry decoys looks natural to flying birds.

“We’re gonna put the decoys in this (five-acre) pasture but not too far out,” Poole said. “You normally don’t want to put decoys near woods or fence lines because Canadas are wary of landing too near woods (because of potential ambushes by predators).

“Then you’ve got to think about how far you want your hunters to be from the decoys. You don’t want to set them up so far away they geese won’t be in shotgun range.”

Hunters should be positioned no farther than 20 yards from the outer edges of a decoy spread. In our case, we violated one of the rules of field hunting by hunkering down near the fence because the ground was so wet. Nobody wanted to get soaked lying down and we didn’t have any field blinds.

Some hunters have good success by hiding underneath camouflage burlap cloth while lying down inside the decoy spread. Some hunters prefer to use hay bale blinds and they work well, but take a little time to set up.

“It shouldn’t matter today,” said Poole, who had patterned the birds. “They’ll be coming from behind us from the east. If we’d gotten out in the field, hidden under camouflage, we’d be looking into the sun at the geese and that’s tough.

“What’s going to happen is we’ll call to them as they fly toward this field and overhead. If they’re gonna land, they’ll turn and their attention will be on the decoys. If they look at us, we’ll be hidden in the shadows of the trees — and the geese also be looking toward the sun.

“With us being about 20 yards from the outside edge of our decoys and the geese trying to land, hopefully, from 20 to 40 yards from us, we should be in shotgun range.”

Hunters also must consider the shot shells they’ll use. Federal law makes mandatory using non-toxic (non-lead) shot, even when hunting fields, so hunters have to use steel shot or some other approved metal pellets.

“The best shot sizes for geese are sizes 1, BB, BBB and T steel shot,” Poole said. “We ought to be OK with BBs or BBBs shot. Another thing to remember is since steel shoots tighter patterns than lead, the best chokes for goose guns are customized and improved modified.”

The final key to getting late-season Canada geese within gun range is calling.

Although most experts believe hunters should call to flocks of flying Canadas that are fairly close, Poole sounded off this morning as soon as he could hear the honkers at a good distance.

“You never know if a bird that hears your call will turn the flock and head for that sound,” he said. “I’ve had geese come from a long way after calling to them.”

Although there are two main types of Canada goose calls, the flute and short reed, flute calls mainly are for hunting over water because they produce quieter and mellower sounds than the short reed. Short-reed calls are versatile and make authentic sounds that broadcast for long distances, ideal for hunting fields where hunters are trying to lure geese from long distances.

“I like wooden calls because they make a mellower sound, but some plastic calls work just as well at times,” Poole said.

The two basic Canada goose calls are the honk and cluck.

When he answered distant geese, Poole blew into the call from deep in his chest, going from a high to low note while saying, “whooo-it.”

Poole and his hunting buddy, Dan “Moose” McLaughlin, had good success luring birds this day. Upon hearing calls, sometimes geese would fly lower, break formation, rapidly change altitude or direction or their wing beats slowed. That meant they were headed for the decoys.

“The main thing is to remain still and not look up at the birds until it’s time to shoot,” Poole said. “They can see movements like that, particularly if your face isn’t camouflaged, and won’t land.”

Poole allowed the first Canada goose that was fooled by the spread to land in the decoys.

“If the others see him walking around, it’ll help bring them in,” he said.

After the lone goose, perhaps a sentry bird, landed, several flocks flew overhead. Poole’s and McLaughlin’s calls lured them close enough that when a flock of 10 birds set their wings and fly closer, the hunters opened up with their guns.

Several birds fell with a thud into the grassy field.

“We’ll leave ‘’em out there,” Poole said. “If we go pick them up, we might scare off other birds flying by.”

Sure enough, within the next 20 minutes, two more flocks of geese tried to land and the shooting resumed. After 45 minutes of intense action, the hunt ended.

“It’s usually like this,” Poole said. “You’ll get birds flying in, shoot them, a few more flocks may come, then the other geese fly to another place. It’s a short morning hunt, but a lot of fun.

“And goose breasts are fine eating, too.”

So even if North Carolina experiences another mild winter and the ducks don’t fly that much down east, do a little scouting to find flocks of Canadas at rural areas. Then visit a landowner to ask permission to hunt.

Piedmont hunters can experience some great wing-shooting for geese close to home while duck hunters travel far and wide to the east, hoping for a glimpse of a mallard, pintail or scaup this month.

Be the first to comment