South Carolina hunters can take lessons from this Greenville man’s history of great dove shoots.

In the beginning, Louis Batson III was his dad’s designated retriever in the dove field — a 5-year-old boy scrambling through corn stalks to pick up birds brought down by the blast of his father’s humpback Browning 12-gauge.

“But it didn’t take long before I ate more than the dog,” Batson said, “so I lost that job.”

He may have lost that job, but Batson has never lost his love for dove hunting.

Now 57, Batson, a Greenville architect, has designs on another prolific season afield when Opening Day for dove season in South Carolina rolls around on Sept. 3.

Over the past 52 years, Batson admits to missing only two Opening Day hunts: the past two years, when he chose to attend his youngest son’s Parents Day festivities at the Air Force Academy in Colorado.

“But I was there for the hunt after Labor Day,” Batson said — and most hunts after that. In fact, despite being a Clemson graduate, you’ll seldom him in the bleachers in Death Valley on a fall Saturday afternoon.

“There’s nothing like a good dove shoot on a crisp day,” Batson said. “That’s why I haven’t been to a football game on a Saturday for years. If I have the chance to go dove hunting, that’s what I’m going to do. We KNOW we’re going to have pretty good dove shooting.”

Need more evidence of Batson’s love for dove?

When Batson was remarried several years ago, his bachelor party consisted of a dove hunt.

“That gives you a pretty good idea of what I like to do,” he said.

Batson is far from alone. Dove hunting in South Carolina is a tightly held tradition — an annual pilgrimage to the fields and barns and barbeques, a social event with multi-generational appeal, and the virtual kickoff to a fall of hunting that is likely to include deer and ducks later on.

There are approximately 45,000 dove hunters in South Carolina, which makes it the second-most popular form of hunting behind whitetail deer. Last year, Palmetto State dove hunters went hunting an average of four times over the course of the season and harvested just under one million birds.

But dove hunting is much more than a numbers game.

“It’s everything rolled into one,” says Billy Dukes, small-game project supervisor for the S.C. Department of Natural Resources. “The traditional and social components of dove hunting are firmly entrenched, and it’s a gateway to hunting opportunity for youths.

“Then there’s a recreation component, and people also are eating these doves, make no mistake. Food may not be the primary motivation for some hunters, but I consider them a delicacy. They’re certainly a treat around my house.”

And around the Batsons’.

“I love cooking doves,” Batson said, “and my mother would rather eat doves than lobster. I think they’re just as good, too. I’ll shoot sporting clays and skeet, but I think I shoot better when there’s meat on the other end of the gun.”

Not that Batson minds when he misses. His long-held strategy is simple and straightforward — just keep blasting away.

“It’s not competitive with me,” Batson said. “If I’m shooting terribly, that’s okay — as long as the dog doesn’t get upset. And if I’m shooting well, that’s okay, too. I’m just happy to be doing what I’m doing.”

Batson comes by his love for shooting naturally. He learned to dove hunt at the hand of his father, Louis Batson Jr., 83, who can still be found under a holly tree at his son’s favorite field on Opening Day.

“He’s got it worse than I do,” the younger Batson said. “He just hasn’t been as scientific about it.”

Indeed, Batson is the first to admit that he thinks about dove hunting far too much, far too often.

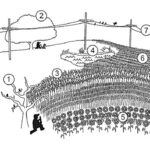

He co-owns a field with Ron Fleming, an Anderson-based wildlife consultant, and they have watched their pet project transformed into a 12-acre field that resembles scenes from the Wizard of Oz.

“It’s a beautiful field,” Batson said. “To see it go from nothing to one heck of a dove field in three years has been amazing.

“And since the architecture business is slow, I’ve got a lot of time to think about it,” Batson joked. “I’m thinking about going to a bigger diameter of wire on our (fake) power poles, and (I) may try pulling dove decoys up onto the wire.”

Batson and Fleming held nine hunts at their field last season, with gunners taking limits during each of the season’s three segments — and all the way until the Jan. 15 closure. The pursuit of such “extended seasons” is a growing trend among South Carolina hunters, according to Fleming.

“Good dove fields are not cheap,” Fleming said, “and when someone makes that kind of investment, they usually want to be able to hunt it more than just on Opening Day.”

Fleming offers plenty of advice in that regard. First of all, he hunts afternoons only, and he stops shooting by 6 p.m.

“I like to give them time to come in and feed before they go to roost,” Fleming said. “If you quit shooting by 6 o’clock, the birds will hang around. If you’re shooting at them all the time, they tend to disperse and find another food source.”

In addition to staggering his plantings so that different food sources are available over longer periods of time, Fleming also monitors the bird population as the season progresses.

“After two or three shoots, if you see the birds dwindling, give it a week or two to build back up,” he said.

Fleming, who worked for 16 years as a wildlife technician for SCDNR before embarking on his business endeavor full-time, said about half of his clients are seeking advice, strategy and assistance in building better dove fields or enhancing existing ones.

He said there’s no minimum-size requirement for a good dove field; his clients’ fields range from three acres to 50.

“I personally like about a 10-acre field, if the topography and pocketbook can stand it,” Fleming said. “Ideally, you’d also like to be at least five miles from another dove field, although that’s not always possible. And if you get a good dove field going, a lot of times somebody’s going to pop up right next to you. All I know is, if you have a good field, the amount of family and friends you have grows tremendously on Sept. 1.”

And that sits just fine with Batson, who relishes the social aspect of dove hunting.

“There’s nothing better than the fellowship of a dove hunt,” Batson said. “It’s not a solitary sport. You’re sitting with your son or your wife or your daughter or a friend’s son who wants to hunt. It’s the first step in becoming a hunter.

“It’s as much the fellowship and time on the tailgate of the truck as it is the hunt itself. It’s the smell of gunpowder and just sitting there seeing the birds. That’s what it’s all about — the shooting is so incidental.”

So, too, is the hitting.

“What’s more fun than watching them twist and dive, or a flurry of them coming in and buzzing the field and everybody’s throwing lead, and the birds come right out the other side, unscathed?” Batson asked. “You’re able to get a good laugh at yourself.”

And therein lies even more appeal for Batson, who is never happier than when he’s on a dove field.

This is, after all, a man who has hunted Africa on two occasions, shooting a lion and Cape buffalo, but ended up having more fun trying to shoot sand grouse as they burst from the tall grasses of the savannah.

Just give him some good old South Carolina simplicity — a shotgun and a good seat on a sultry opening day — and Batson is more than content.

“It’s low-impact,” he said. “All you need is a pair of khaki pants, a $7 camo shirt, a cap and a 5-gallon pail, and you’re good to go.

“There’s not any hunting I don’t love, but I may never shoot a big deer. And I’ll be shooting doves when I’m wheelchair-bound.”

Be the first to comment