Lake Norman is an oft-ignored venue for the challenge of huge catfish.

Little kids, big kids, even old guys like to catch catfish.

Coming in a variety of species, catfish are widely distributed in the Lower 48 states.

Many of us got our first fishing experiences catching catfish from a nearby pond or stream. Nonetheless, as a gamefish, catfish are undervalued.

Big catfish pull hard. They don’t leap like smallmouth bass or rainbow trout. Yet for a steady and strong pull, catfish acquit themselves as well as any other gamefish.

However, North Carolina is one of the states that doesn’t classify catfish as gamefish.

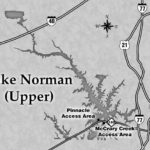

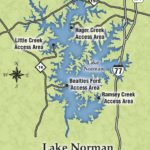

In recent years Lake Norman, the 32,510-acre impoundment formed by a dam of the Catawba River north of Charlotte, has become a mecca for anglers seeking a big fish to stretch their line.

Check Tony Garitta’s column, “Line Scores from the Livewell” in this issue for results of the North Carolina Catfish Association tournaments. You’ll see some big fish taken from the once-named “Dead Sea.”

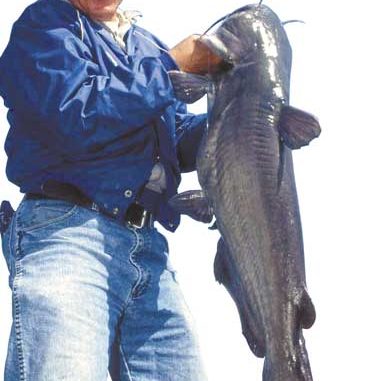

While neither blue catfish nor flathead catfish are native to Lake Norman, both species thrive there. Genuine trophies are fairly common, whether a blue or flathead. Twenty-pounders are scarcely noticeable among Lake Norman’s catfishing clan.

“Points, that’s where we’re going to catch them today,” said Mac Byrum, among the best if not the best catfish guides at Lake Norman as his boat dropped off plane and he began to rig rods. “This time of year, the big ones are all on the points.”

Byrum uses cut bait exclusively. He cuts pieces of crappie or brim into strips about

1-inch wide the length of the baitfish.

“For (bait) fish such as crappie, where there is a size regulation, you have to keep the entire carcass intact — head to tail,” he said. “That way, the Wildlife Resource Commission officers can confirm that only legal fish were used.”

Byrum also scaled the crappie as he sliced fillets for bait.

“I think once the scales are off the bait gives off a little better odor,” he said. “Catfish depend a lot on scent and the scaled piece offers a little better scent trail.”

In addition to crappie strips, Byrum also used strips of small live bream and live minnows. His set-ups were effective as he landed catfish with each technique.

While many catfish anglers discard a piece of cut bait after it gets chewed on, Byrum uses a cut bait until it’s absolutely gone.

“I use a cut bait until there’s not much left,” he said. “I think a cut bait that caught a fish preserves the scent of the previous fish and attracts then next one.”

With bream, Byrum likes to leave the tail on the cut bait.

“The tail, I think, gives the chunk of bait a natural sort of movement,” he said.

Jerry Hildebran of Sherrill’s Ford also is a successful catfish tournament angler.

“In summer, I use cut bait for blues,” he said. “Usually I use big gizzard shad and cut it into chunks.”

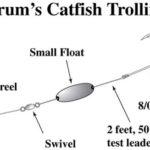

Bryrum arranged six Shakespere Ugly Stick catfish rods off the stern, three on each side. The lines on the outside were at 75 to 90 feet, the inside lines were at about 125 feet, and the center lines were intermediate of the others.

“With the lines at this length, if you want to turn tangles are minimized,” Byrum said. “At the speed I go, it’s pretty rare that the lines tangle.”

Once the lines were in the water, Bryrum put his trolling motor in the water and operated it by remote control.

“Half a mile an hour or less is the preferred speed for trolling,” he said. “With the GPS on the depth-finder, I can tell just how fast we’re moving.”

But Hildebran uses a different technique for blue catfish during N.C.’s warmest months.

“In summer I usually drift,” he said. “Main lake points are the places the blues are found.

“If the wind is up, I use a drift sock to control the speed. If the wind is calm, I use the trolling motor to keep the bait moving. Drifting is a great way to cover lots of water.”

A drift sock is a large, triangular bag with a big hole at one end and a small hole on the other. Dangled off the side of a boat, it slows the rate of a boat’s movement in high winds. Depending on where the drift sock is attached to the boat, the direction and speed of the drift also may be controlled.

In contrast, Hildebran usually anchors when seeking flatheads.

“I set up on main lake points,” he said. “If I’m after flatheads, I use live bream or live white perch for bait. Those white perch are all over Lake Norman and the flatheads love them.

“At the points, I cast the baits out in a big circle around the boat then I wait until somebody comes by and grabs one.”

When fishing in this manner, Hildebran uses 1 1/2- to 2-ounce egg sinkers to hold baits near the bottom. Flatheads often can be noticed on depth-finders yet remain inactive despite lively baits in the water.

Suddenly, rods around the boat dipped toward the water and big flatheads were on several rigs at the same time. The result was instant mayhem.

Night is a particularly good time for flatheads.

“I fish nights, partly to avoid the boat traffic,” Hildebran said. “Flatheads are out then, too. Some nights, not much goes on, but some nights, there are lots of flatheads.”

Byrum and Hildebran start the search for Lake Norman catfish operating their boats in 20 to 30 feet of water.

“I start in water than deep and move deeper or shallower as seems to be needed,” Hildebran said. “I don’t try to tell the fish how deep they should be.”

As a caveat, Byrum said he put the big engine in gear when he shut it off.

“If the engine is in neutral, the blade will rotate as we move,” he said. “If we hit any line left by other anglers, the rotating blade will simply wind the line around my prop. Then, when I fire up the engine, the wrapped line may possibly break the seals and cost me a lot of money (to repair).”

When we got to a point ahead of the boat, one of the rod tips dipped toward the water and line peeled off the reel. A catfish had made his presence known.

Lake Norman is fortunate to hold trophy catfish of two varieties, blue catfish and flathead catfish.

“The blues and the flatheads strike differently,” Byrum said. “The big blues hammer it. They grab the bait and take off.

“In contrast, the flatheads take a bait and sort of mush it about. If the rod tip slowly bends toward the water and stays there, chances are it’s a flathead.”

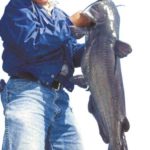

Byrum’s setup included 25-pound test line, a swivel and a 2-foot 50-pound test shock leader. His line choices were the same as Hildebran’s. Ahead of the swivel, Byrum used a 2-ounce “slinky” or snake sinker. The “slinky” sinker is merely a long, narrow weight wrapped in fabric, heavy enough to keep the bait near the bottom. The fabric cover helps prevent snagging on the bottom.

Hildebran also uses the “slinky” snake weights when drifting for blue cats. Between the swivel and the bait, Byrum rigged a small float that lifts the bait away from the bottom and into the vision of patrolling catfish.

When the first cat hit, Byrum was an able coach.

“Before lifting the rod out of the holder when a cat hits, turn the reel handle 4- or 5-times,” he said. “Take a little slack out of the line. We’re using circle hooks so we don’t need to yank hard to set the hook. When the line comes tight, the circle hook will pull into the corner of the cat’s mouth.”

Hildebran uses Kahle hooks. Similar to circle hooks, Kahle hooks are designed for fishing with baits comparable to what Byrum and Hildebran — and other catfish anglers — use. Byrum and Hildebran use huge hooks — 8/0 is a common size.

If the big cats are shallow and are in wide places, Byrum uses planer boards to swing the baits into spots the boat may not be able to maneuver. Planer boards are small wooden or plastic boards with a line tied on one end attached to the boat and a small clip on the other where the angler’s line is attached.

The angle at the front of a planer board pulls the angler’s line away from the boat. When a fish strikes, the line in the clip pulls free, allowing the angler to deal with the fish with a direct line from the rod tip to the fish.

“Planer boards are useful for the wide open parts of the lake and not so useful in the narrow spots where we’ll be fishing today,” Byrum said.

Byrum is friendly and entertaining in a boat. When the fishing slowed a little, as it always does, we told tales about our friend from Hickory, the late Jim Ledbetter, known for his TV show “The Piedmont Sportsman.”

We’d fished with Ledbetter and held him in high regard. Among the lessons Byrum learned from Ledbetter was to approach fishing a large lake as one would to solving a puzzle.

“Lake Norman is a big place,” Ledbetter once said. “If you really want to learn to fish Lake Norman, for catfish or anything else, don’t try to learn the whole lake; learn it a section at a time.”

If you want to know more about catfishing, check out Catfish1.com and go to “Mac Byrum’s Catfish University.” On the Catfish1.com home page, look to the upper left hand for an entry called “Site Navigation.”

Among the items listed is “Catfish Publications” and at the bottom of the list is “Mac Byrum’s Catfish University.” It contains much more information than could be included in this story.

In any event, any Tar Heel angler wishing to get a major “string stretch” should consider Lake Norman catfish.

Big blues can peel off yards of line at a time, while large flatheads like to burrow to the bottom and dare anglers to crank them to the surface.

Lake Norman as a catfish location and catfish as gamefish often are overlooked. Any angler who ignores Lake Norman’s Mr. Whiskers as sporting challenges doesn’t know the cat’s meow when he hears or sees it.

Be the first to comment