Graham County has everything a North Carolina fisherman could ever want.

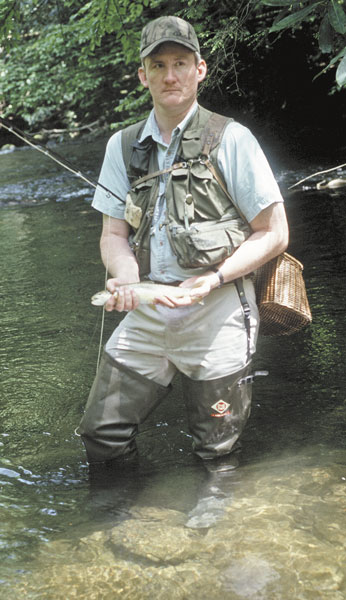

Marty Maxwell of Robbinsville, a masterful fly fisherman by any standard of measurement, also happens to be a student of Horace Kephart, the man known as the “Dean of American Campers,” Indeed, when he wrote his thesis for a master’s degree in history at Wake Forest University years ago, Kephart was the subject.

The mention of advanced academic degrees in an outdoor magazine may seem strange, but it all becomes clear as the water of a tumbling mountain trout stream when you realize that Kephart came to the North Carolina high country in search of a region he described as being “back of beyond.”

This is where trout flourish

That sort of country — remote, wild, relatively pristine, and sparsely populated — is precisely the sort of place where trout flourish. Maxwell grew up in Graham County in the extreme southwestern corner of North Carolina, learning the tricks of the trout-fishing trade under the tutelage of an adoring grandfather.

Like Kephart, Maxwell came to appreciate the appeal of mountain fastnesses, and by the happy accident of his birthplace, he was perfectly placed to become a trout fisherman. Other than his years in college, he has clung to his Graham County roots and has 50 years of incomparable angling experience on his home waters.

What follows is an overview of the trout-fishing paradise that is Graham County, seen in large measure through Maxwell’s experiences on some of the best waters in a county blessed, thanks in large measure to containing vast tracts of the Nantahala National Forest, with an abundance of great trout fishing streams.

SLICKROCK CREEK

Over much of the course of its flow, Slickrock Creek forms the boundary between North Carolina and Tennessee. The stream has a number of special or unique features. Unlike most of Graham County’s creeks, which feature a mixture of browns and rainbows — or, where natural barriers have prevented upstream migration, brook trout — except for its uppermost reaches, Slickrock is home exclusively to brown trout. After the U.S. Forest service purchased the watershed in 1936, Civilian Conservation Corps workers made the long hike to Slickrock Creek carrying fingerlings in specially constructed backpacks.

The browns found the habitat, which was last logged in 1922, to their liking and immediately began natural reproduction, or as locals put it, “took holt.” Browns have thrived in Slickrock ever since this original implantation, with no further stocking having been needed or attempted. The descendants of these Depression-era imports, with vivid red spots and golden-bronze bodies, are truly lovely fish. As tends to be the case with brown trout everywhere, they can be capricious. Hit Slickrock Creek when things are right though — the midst of a springtime Green Drake hatch, for example — and you will understand why an area resident once spoke of it being the “backside of heaven.”

Add camping to your fishing trip here

In addition to its plentiful, if sometimes fickle, population of wild browns, Slickrock Creek has several other characteristics that add to its appeal. It is in a designated wilderness area, and the sole means of access is on foot. The most common approach is from Calderwood Lake at the creek’s mouth, but for the angler with a high degree of fitness, a better one is hiking in from Big Fat Gap (The trailhead is reached by a U.S. Forest Service road off US 129). The trail drops more than 1,000 feet in a mile, and the climb back out is a strenuous one indeed. On the other hand, when you reach Slickrock Creek near its juncture with Nichols Cove Branch, you are in some of the stream’s most-productive water.

The best way to fish Slickrock is to camp and make day hikes from the site where you pitch your tent. As so often holds true in this part of the world, the further upstream you go, the fewer folks you encounter and the better the fishing.

BIG SNOWBIRD CREEK

Big Snowbird might be described as a stream with a split personality.

Downstream from “The Junction” (an old railroad turnaround that marks the end of Forest Service Rd. 1120, also known as Big Snowbird Road), the stream is standard put-and-take stocked water. It should be noted, however, that there are also plenty of wild fish in this stretch of the stream. From the road’s end upstream, however, there is no stocking, and regulations change from “Hatchery Supported” to “Wild Trout.” For more than three miles upstream from “the junction,” anglers will find a mixture of wild rainbows and browns, with the former being more plentiful. Then, a short way above where Sassafras Creek enters Big Snowbird, things change dramatically.

This is truly a fine brook trout stream

A series of cataracts known as Mouse Knob Falls drops the stream several hundred feet in a quarter of a mile. This sudden change affords an effective barrier to upstream migration by rainbows and browns, and from the head of the falls where Mouse Knob Creek enters the main stream from the right, the angler encounters nothing but brook trout, or, as mountain folks call them, specks. Interestingly, long stretches of the upper reaches of Big Snowbird are quite flat, although the spectacular Middle Falls and the massive pool at its foot present a dramatic contrast.

Big Snowbird is probably North Carolina’s finest brook trout stream, and certainly it has the largest, longest stretch of water where brook trout hold exclusive domain. Mile after mile of drainage, and surprisingly large, open water, beckons invitingly. For those who really like to get off the beaten path, it might also be noted that a number of feeder streams to Big Snowbird’s upper reaches hold natives as well.

BIG SANTEETLAH CREEK

Although its lower reaches have declined from their one-time glory days, Big Santeetlah remains a fine fishery.

The N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission first poisoned much of the stream to eliminate trash fish. Twenty years later, they restocked otters, which are fantastic fish-catchers. Marty Maxwell said the stream has never regained its original character, but remains a good test for trout fishermen.

As you get higher upstream, Big Santeetlah, there are fine populations of browns and rainbows. Access is by Forest Service Rd. 81, which turns off the Joyce Kilmer Rd. just after you cross Santeetlah Gap and the Cherohala Highway begins.

If you want some solitude, try a day on Wright Creek, Big Santeetlah’s largest feeder creek.

OTHER STREAMS

Along with the “big three,” there are many other streams which merit at least passing mention. Yellow, Stecoah, Panther, Long, West Buffalo, Sawyer, and Talula creeks are all designated as Hatchery Supported waters. Most of these creeks, all of which are relatively small — 10 to 25 feet wide — hold decent populations of wild trout as well.

Little Santeetlah Creek, which flows through the heart of famed Joyce Kilmer Memorial Forest, is wild-trout water, holding plenty of small but vividly colored rainbows. Deep Creek, which empties into the Cheoah River along US 129 a few miles northwest of Robbinsville, is one of the relatively few streams in the state carrying a Wild Trout designation where it is legal to use natural bait. The same holds true for the uppermost reaches of Long Creek. Little Snowbird Creek is full of trout, but most of it is private water, either part of the Cherokee Indian Reservation or controlled by a fishing club.

These waters are diverse, and so is access to them

Altogether, Graham County is home to more than 200 miles of trout-holding water, and it ranges from “drive-to-streamside-and-be-fishing” streams to those accessible only by an arduous hike or even by “brush busting” into areas not even served my maintained trails.

It’s a small wonder that Maxwell once said, “I reckon I’ve been mighty lucky. I grew up in a trout-fishing piece of paradise and was fortunate enough to have a grandfather to teach me all the tricks of the trade.”

EDITOR’S NOTE — Jim Casada is a full-time freelance writer who grew up in the heart of the North Carolina mountains. He has written or edited more than 30 books including the award-winning Modern Fly Fishing and the Beginner’s Guide to Fly Fishing and most recently, his Fly Fishing in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park — An Insider’s Guide to a Pursuit of Passion. His books are available through his website (www.jimcasadaoutdoors.com) as is a free subscription to his monthly e-newsletter.

Be the first to comment