South Carolina’s artificial-reef sites draw a variety of species that can keep fishermen busy year-round.

When the summer sun starts to simmer the South Carolina surf, it’s a great time to shove off toward the eastern horizon. There, the water depths provide fish an escape from the heat and an ample supply of oxygen.

But it’s a very big expanse of blue that awaits you out there, so simply fishing deeper is unlikely to produce much action. That’s why locating artificial reefs can be a key to success. Hit the right fish hangout — a pile of concrete rubble, a stack of New York subway cars, a sunken barge — and you could find yourself “wearin’ ’em out.”

Capt. Brian Davis, who has been fishing the waters around his native Charleston for more than 25 years, knows the location of area reefs and what will be biting at any particular time of year. During his time on the water, he’s also developed a deep appreciation of the area. “The waters off Charleston have an abundance of gamefish,” Davis said. “There’s a lot of quantity and variety out there.”

Along with numerous man-made reefs, the coastline is blessed with several square miles of natural livebottom. Both attract black sea bass, weakfish, Atlantic spadefish, Spanish mackerel, king mackerel, vermilion snapper, and many more bottom-dwelling fish.

On a trip on his 22-foot Nautic Star last June, Davis limited his travel to the nearshore reefs, although he’s equipped to work the offshore reefs as well. For fishermen who would rather not venture too far out, there’s plenty of action to be found within 10 miles of the beach.

“Spring and fall are the two best seasons for bottomfish,” Davis said, “but there’s always something biting out there year-round.”

Depending on the time of year, Davis said that a wide range of species will be available, along with the plentiful black sea bass.

“You can find barracuda, juvenile grouper and red snapper, redfish, triggerfish (and) spadefish,” Davis said. “There’s also a lot of flounder, weakfish, jack crevalle, king and Spanish mackerel.

“The bigger grouper, snapper, sailfish and so forth are usually on the offshore reefs.”

If you’re concentrating on sea bass, you’ll normally find them in 40 to 120 feet of water. The best fishing, however, is usually on ledges and reefs with livebottom areas in 50- to 70-foot depths. Sea bass stay close to structure, so it’s crucial to anchor over or near the reef, or to re-start your drifts as soon as the fish quit biting.

Fishing for the 1- to 3-pound juvenile sea bass on the nearshore reefs doesn’t require heavy tackle. Davis recommends a 7-foot, medium-weight rod and a mid-sized reel that holds 180 yards of 30-pound braided line.

“When I’m fishing for sea bass,” Davis said, “I usually use a Carolina rig with a 1-ounce weight and a swivel with a 30-pound mono leader and a 3/0 circle hook. You can use live bait or artificials. I use a lot of Berkeley Gulp! lures like the 3-inch shrimp or the 1-inch fiddler crab. My favorite color is white for visibility.

“You can also use a ¾- to 1-ounce jighead with a Berkely Gulp! shrimp, a live shrimp or a mud minnow to catch different sorts of fish.”

Another method Davis has found to be a fun alternative to the bottom-fishing normally associated with reefs involves fly-fishing tackle and a popular species of gamefish that spend the entire summer close to the shoreline.

“If you haven’t done Spanish mackerel on a fly rod,” he said, “you’re missing out. It’s a lot of fun, and you can catch a ton. I like a Clauser minnow in white, blue or chartreuse. The Spanish really hammer it.”

During his quarter-century plying the waters off Charleston, Davis has been able to take advantage of reef sites, but those fish magnets haven’t always been there.

“The state’s official reef program actually started in 1973,” said Bob Martore, artificial-reef coordinator for Marine Resources Division of the S.C. Department of Natural Resources. “Prior to that, individual fishing clubs had begun making their own reefs by dumping tires, washing machines and anything they could find into the ocean.

“The state realized that could get messy pretty quickly, so they founded the reef program to control the situation. It wasn’t a funded program, just a way to manage permits and keep track of what went into the ocean.”

Martore said that the program grew more sophisticated as the importance of the structures in maintaining healthy fish populations became more apparent.

“Through the years, by trial and error for the most part, the department learned the best materials and how to configure them,” he said.

Today, the reef-building program receives funding from the sale of saltwater licenses.

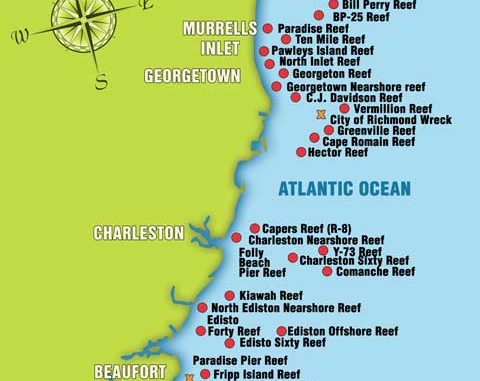

“We now have 45 reef sites along the coast,” Martore said, “We call them reef sites rather than reefs, because there are usually a number of different materials on any one site. And these usually cover large areas, up to about a half-mile square.

“We might sink a tugboat, a couple of barges and several concrete units that we make specifically for artificial reefs.”

These days, the department constantly monitors the sites to see which materials are most effective, and what number and type of sea life is gathering there.

When it comes to the depth of the typical artificial reef, Martore explained that it’s pretty much across the board.

“We have some that are inshore, such as Winyah Bay and Port Royal Sound,” he said. “The shallowest is about 10 feet deep, while the deepest is around 120 feet. Their locations range from fishing piers to 35 miles offshore.”

Martore said that concrete has proven to be the most effective for establishment of sea life on reef sites.

“It’s very similar to the natural limestone ledges that are found offshore,” said Martore. “The concrete mimics that very closely and gets colonized quickly. Usually in a matter of weeks, there will be growth on the concrete, and by six months to a year, the entire unit is covered.”

Along with the concrete “reef cones” designed specifically for reef sites, other concrete materials such as chunks of roadway, culverts, and bridges are often utilized.

“We were able to haul away 250,000 tons of material from the old Cooper River Bridge,” said Martore. “It went to 12 different reef sites along the Charleston County coastline.

“But we still like to use more complex materials too — like ships, for instance. Ships are nice because they’re big structures with a lot of internal spaces for protecting smaller fish. That allows them to avoid predation and grow to become spawning fish.

“The long term goal of building reef sites is to provide habitat so that we can rebuild fish stocks. We don’t want things to become over-fished.”

Davis loves to work offshore sites, where he can find his favorites — grouper and red snapper. Like sea bass, these fish don’t stray far from the protection of the reefs. While offshore reef fish can range from one to 40 pounds, Warsaw grouper may exceed 300 pounds.

Cut squid, cigar minnows and sardines are preferred for red snapper and are effective on grouper. Live or cut vermilion snapper are excellent for grouper. Cigar minnows and live bait should be fished from just off the bottom to 10 feet above the bottom. You can also try jigging lures, dropping live menhaden or trolling on down-riggers.

Be the first to comment